David P. Gushee calls them “conscientious objectors” -- people who have left the evangelical movement.

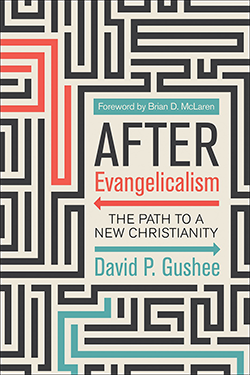

He is one of them. But even though he has left evangelicalism behind, he is still a Christian. And in his latest book, “After Evangelicalism: The Path to a New Christianity,” Gushee offers a way forward for those who have left the fold.

“My agenda is to help minister to those who have already left or been kicked out or been wounded, to help them see that the problem is not Jesus,” he said. “The problem is an unhealthy expression of the Christian faith.”

“My agenda is to help minister to those who have already left or been kicked out or been wounded, to help them see that the problem is not Jesus,” he said. “The problem is an unhealthy expression of the Christian faith.”

Gushee is Distinguished University Professor of Christian Ethics and director of the Center for Theology and Public Life at Mercer University. He has previously served as the president of the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Christian Ethics.

He is a prolific writer and commentator who has contributed to outlets including Religion News Service, Sojourners and Christianity Today. He also is the author of dozens of books, including “Still Christian: Following Jesus out of American Evangelicalism.”

He has an M.Div. from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. and an M.Phil. from Union Theological Seminary.

He spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about his new book. The following is an edited transcript.

He spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about his new book. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Mainline Christians have been worried about the decline in numbers for some time, but you argue that this is something also the evangelical movement needs to recognize. What are you seeing in terms of the numbers?

David P. Gushee: There’s a lot of good polling since about 2016. I triangulate the different studies to put a rough number on the evangelical exodus. Just as a minimal estimate, I suggest that evangelicals have lost 25 million in recent years and that they are predominantly young and they are leaving primarily because they find something objectionable about what has become a white evangelicalism.

I think the mainline Protestant numerical decline has been about a number of things, but it hasn’t fundamentally been about moral objections to the content of mainline preaching or politics or ethics.

On the evangelical side, the departures are often matters of intellectual incoherence or matters of moral objection and, in some cases, trauma. I think this definitely marks the evangelical exodus.

F&L: You refer to them as “conscientious objectors.” What do you mean by that?

DG: I think that, especially but not exclusively, younger evangelical exiles are leaving because they think there is something toxic or ungodly or damaging about major trends in evangelicalism.

Main examples would include the inability of evangelicals to figure out how to handle sexuality in a way that doesn’t demonize or harm women and LGBTQ people; the inability of white evangelicals to ever really come to terms with white racism; the way evangelicalism seems to demand a posture toward science that requires shutting down or denigrating mainstream science; and the way that the white evangelical embrace of the Republican Party appears to have no limits, so that even when somebody like Donald Trump is running, white evangelicals are willing and able to support him.

Also, there is a subset of evangelical conscientious objectors who have experienced sexual abuse or sexual misconduct in evangelical churches that has been covered up or not adequately addressed in one way or another. There’s a clergy sex abuse or church leader sex abuse problem that is surfacing more and more.

There’s kind of a matrix of masculineness -- power structures in which basically unaccountable leaders, men, dominate their churches and are almost beyond any kind of check and balance.

This is bearing bad fruit from many decades of anti-Democratic and anti-feminist and, you might say, anti-accountability tendencies among evangelicals.

F&L: What argument do you make as a person from this tradition to the young people who may be saying, “I’m walking away from evangelicalism. I’m walking away from Christianity”?

DG: I no longer make an argument that people who are in the evangelical subculture should stay.

What I’m hoping for is that if they can see some ways to rethink some of the main things they’ve been taught that don’t work for them, if they can see some ways to rethink those bad ideas and bad practices, then they might be able to rediscover Jesus and a viable practice of the Christian faith.

But I have definitely personally concluded that, for me, following Jesus means leaving evangelicalism behind, and I hold no brief toward the preservation of evangelicalism.

There may be some people who will read the book who will see it as a roadmap for reform within evangelicalism. I hope so, but that’s not my agenda.

F&L: What do you hope people in this audience of evangelical exiles will gain from your book?

DG: One clue is found in the cover art. You see that it’s a maze. The controlling metaphor is that a lot of former evangelicals are like people who are stuck in a living maze. They can’t get out. They were taught something and they couldn’t figure out how to get past it, so they got stuck there.

You might say that the book is designed to open paths out of the blocked-up maze, to get through and out to the other side, where they can breathe some fresh air and they can realize that, “Oh, my problem was not with this thing called Christianity.

“My problem was with this version of Christianity. So maybe if I can leave that version of Christianity behind and deal with some of the problems that has left me with, maybe I can find my way to faith in Jesus again.”

F&L: You say in the book, “A term I will offer to describe the vision of Jesus I am embracing is ‘Christian humanism.’” What is this new vision, and why do you call it Christian humanism?

DG: It’s a call for humaneness and a compassion-oriented Christianity, as opposed to intolerance and rigidity. It’s a call to the recognition of human potential and the respect for human difference.

By calling for an openness to the wider world, a willingness to engage with what science and human beings themselves have to tell us, and a humane and compassionate orientation toward people, there could be a path forward that would get beyond some of the worst impulses of evangelical Christianity as I see it.

F&L: In the section about race, you quote theologian Eboni Marshall Turman saying, “White Christianity in America was born in heresy.” Talk a little bit about your own reaction and then what that statement means for white Christians today.

DG: Professor Turman is a dear friend of mine now and colleague in Christian ethics. She said that at the American Academy of Religion meeting plenary in 2019, related to the legacy of James Cone.

What struck me about it at the time was she said it without feeling the need to make an argument to support it, because she just knew it was true, and she was building upon a couple of generations of scholarship that have been showing why that is true.

My own thinking about the way white supremacy and white racism has damaged American white Christianity had already, by 2019, progressed to the point where I was able to just nod my head and say, “Well, that’s absolutely right.”

But I was also thinking, “Most church folks that I know still would really struggle to make sense of that statement.”

White American evangelical Christianity has been less willing, generally speaking, to deal with a scholarship that challenges racism embedded in its tradition.

F&L: What do you recommend that white ex-evangelicals do with this information?

DG: What I ask post-evangelicals to do with that information is to go out of this subculture and to look for the Christianity that is consciously attempting to be anti-racist and to engage the world of African American and Latinx and Asian American theology and preaching and scholarship -- in other words, to get out of the white ghetto.

They need to read more widely and realize -- and I try to model this at the end of that chapter -- that there’s brilliant scholarship being done on every aspect of Christian theology, biblical studies and ethics by scholars of color, and that a first step for those of us coming out of this subculture is to dive into that literature and listen closely.

F&L: You name a number of different things that have pushed people out or caused people to be pushed out. To what degree do you think the embrace of the Republican Party is a factor?

DG: I think it is a major factor. The fact that 81% of white evangelicals went with [Trump] and are among his strongest supporters today is staggering to a lot of people who are in the evangelical community -- or were -- and consider that to be a disaster and a complete repudiation of everything their parents and grandparents taught them about what it means to be an evangelical.

Maybe the question isn’t, “How could evangelicals violate their principles to support Donald Trump?” Maybe the real question is, “How is Donald Trump in keeping with the actual way of life of evangelicals?”

The book that I point to now that gets to one aspect of this better than any others is Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s “Jesus and John Wayne,” dealing with masculineness and toxic masculinity.

Her critique is that evangelicals have liked to define themselves in terms of theological essentials like Scripture or a high commitment to evangelism and missions, but what appears to be defining white evangelicals is whiteness, patriarchy, authoritarianism, and a kind of nativism and anti-elitism. In that sense, Trump actually fits with large parts of evangelicalism rather than being a violation of it.

It’s just missionally, ecclesiologically disastrous that this is the direction that evangelicals have gone. It’s a religious community that is shedding people because it is shrinking into a kind of hot, molten core of white reactionary movement, and everybody who does not find that appealing is looking elsewhere.

In the historical chapter, I make the case that the people who rebranded fundamentalism as evangelicalism in the ’40s intended to build a coalition of people who were willing to call themselves “evangelicals.”

They tried to thin down the theology enough that everybody from high Reformed to Wesleyan Methodists to Anabaptist Mennonites to the ethnic churches like the Dutch Reformed to the Swedish Lutherans and, oh yeah, some people of color, if they’re willing to play ball on our terms, could all be grouped under the evangelical label.

I conclude that they were largely successful, and they’re socially constructing that identity and getting everybody to be grouped under that identity very broadly.

But some of these tendencies are far worse in some parts of this grand evangelical coalition than they are in other parts. I argue that some of the smaller, less typical and frankly morally healthier subcommunities would probably be best declaring themselves divorced from evangelicalism and going back to just being who they are.

F&L: Stepping out from under that umbrella?

DG: Yeah, because the umbrella itself is leaking toxic rain or something. So get out from under and breathe your own air, and don’t listen to what the supposed evangelical authorities tell you is how things should be.

F&L: Is there something you want to add that I didn’t ask about?

DG: Where this began for me was getting direct messages on Facebook from strangers, mainly LGBTQ evangelicals or ex-evangelicals or wounded evangelicals, just after I wrote my book called “Changing Our Mind” in 2014 that called for inclusion.

I heard from hundreds of people saying basically, “Well, I thought God was condemning me or I was doomed to hell, but I read your book and now maybe I have some hope.”

That was my first encounter with a very large community of people who found evangelicalism destructive spiritually. But since then, I’ve realized that there are a whole lot more people in that category, so this is a book for them.

It’s a book that some of your readers could give to their church members or to their church members’ children to say, “Hey, there is hope. There are ways to think about these things that don’t exile you from the church. They may exile you from that church over there, but not from the church of Jesus. There’s a future.”

I’m also saying to the mainline, “Ex-evangelicals are coming to the mainline churches.” Not always, but some of them are, and I’m hearing about them coming.

It’s different, and it’s a culture thing.

If you grew up in a praise-and-worship, blue jeans, no-liturgy, guy-at-the-front-preaching-for-45-minutes kind of evangelical church and then you go to a First Methodist church or whatever, the cultural difference is profound.

But if church leaders can recognize wounded ex-evangelicals when they come to the door and then have something to offer them, that is significant ministry at this moment.