Before establishing herself as an expert on book banning, Emily Knox was a student of religion. Raised Episcopalian, Knox always had an interest in religion, with her academic pursuits including a year of study abroad in Jerusalem.

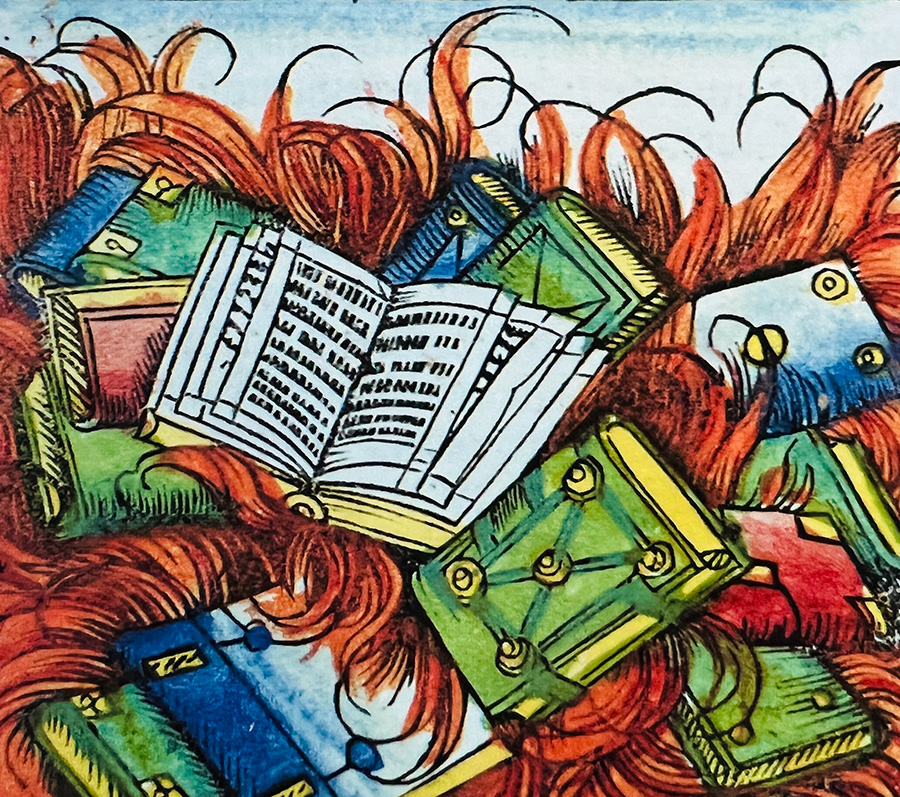

The author of “Book Banning in 21st-Century America” sees connections between the importance people place on books and reading and the visceral reaction some have to exactly which books are or are not accessible. Banned Books Week is Sept. 18-24.

“After the murder of George Floyd, all these reading lists started showing up, because that is how we think about people learning things. Our entire educational system is based on this, in a way that it’s actually hard for us to see,” Knox said.

“My entire job is basically based on giving people things to read and having them interpret them. Looking at book challenges, [they are] the negative reaction that shows us how important reading is to our lives. When someone says, ‘No, you should not read this,’ then we can see how reading is so important, why books are so important, why texts are so important.”

Knox, an associate professor in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in religious studies before pursuing additional advanced degrees in communication, library and information sciences.

She spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne this summer. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Your work is in library science, but your first degrees are in religious studies. What led you to those first two degrees?

Emily Knox: I was always interested in religions as a whole. I am an Episcopalian; I was raised Episcopalian. So I’ve just always been interested in religion. I would read all the books in my parents’ house about religion, like world religions. When I got to Smith, I decided that that’s what I wanted to study. And honestly, I’m so glad I did. I learned a lot about the world and people and ideas.

I really focused on the sociology of religion. I studied evangelicalism and fundamentalism in the United States. I decided to go to Hebrew University in Jerusalem for my junior year abroad, which was probably one of the most important things I’ve done in my life. It taught me a lot about religion’s influence over current political issues in a way that is difficult to understand when you just look at news reports. One of the best classes I ever took was called Sociology of Israel. It was looking at all the different people who had come to or were already living on this land that does not have a lot of resources, and how that plays out.

After getting my degree at Smith, I decided to go to University of Chicago, because I thought I was going to get my Ph.D. in religion. I was in the master’s program, still doing sociology of religion, and I realized I needed a break, so I stopped.

I decided to go to University of Illinois to get my master’s in library and information science. My dad was a professor, and my mom was a librarian. She always encouraged me to get my library science degree, and so I decided to do that. Then I worked as a theological librarian at General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York City. I really enjoyed doing that. I could combine both my faith and my profession. All the students there live in community. That was just a very different and rewarding job. I really liked working for the church that way.

Being a reference librarian, and then I was later associate director, I learned a lot about running a library but also running a library that is a component of faith and service. I was involved in the American Theological Library Association. That’s a great group. It’s one of the few groups that are truly interfaith. When you go to a conference, there are people from seminaries and also large universities with seminaries attached. There are people who are atheists; there are people who are Muslim; there are people who are Jewish. It’s a truly interfaith organization, and it’s one of the few that I know that works really well, because the job is always how do we provide information for our patrons in whatever religious contexts that we’re in.

I decided to get my Ph.D., and I decided not to go back to religious studies. I thought about it, but I knew what I wanted to study, which was why do people ban books. This actually does come from my religious studies background, because I was interested in right-wing Christian youth movements. A lot of times, but not always, books are challenged for religious reasons. Sometimes those challenges play themselves out as social reasons, but often they’re due to the religious convictions of the people doing the challenges.

F&L: Were you seeing an increase in book challenges and book bans at that point?

EK: No, I wasn’t. I’ve just always been interested in banned books. As I said, my mom was a librarian. We would always observe Banned Books Week. She’d bring home the list of books; they were often books that I really loved. Judy Blume was on that list all the time. So I always was interested in banned books. I would say that, no, when I was working as a librarian, that wasn’t a huge issue, especially in my library.

When I was in the library, the major issue was the consecration of Gene Robinson; he was a bishop and a graduate of General. One thing we had in our library — and I talked to my students about this a lot — we collected everything on Anglicanism and the Episcopal Church. We had things that were both pro- and anti-inclusion of LGBTQIA people in the church. We collected a lot at that time about Mr. Robinson’s consecration. I felt like that was the most important thing we could do, to provide a record and let our students and patrons really know about what the discussion was at that time. Whether I agreed with that discussion or not, or my director did, that wasn’t really our job as librarians at the seminary. Our job was to let the seminarians know that these are issues that are important for the church going forward.

F&L: It sounds as if you anticipated the season we find ourselves in now. Given that it is such a particular area of interest and expertise for you, could you speak about how we have come to this moment?

EK: I wrote “Book Banning in 21st-Century America” in 2015. That book is based on my dissertation, which was in 2012.

Book bannings are a reactionary practice to changes in society. They’re always a lagging indicator. What I can tell you is that we are having so many book bans now because our society is in such upheaval. We went through the election of Barack Obama, the reactionary election of Donald Trump, then the pandemic. It is not surprising that we would have book bans.

These really started in September 2021, one school year after the pandemic started. Another thing that happened with the pandemic that I think is incredibly important is that it brought school home. I think a lot of parents did not know what their kids were learning in school. I often talk about school being a black box you send your kid off to.

That was not true during the pandemic. You saw much more about what your kids were learning. Of course, educational theories and pedagogical theories have changed quite a bit over the past 10 years. There’s really much more emphasis on not just diversity and inclusion but also emotional intelligence. The examples that teachers use are different. The way that kids are taught is not necessarily the way I was taught, or even people who are slightly younger than I am were taught.

That’s a main thing that I see happening right now with book challenges. But there’s always one throughline with book challenges, and this comes from my religious studies. I focus quite a bit on the importance of reading and the text, and actually the book itself, in my theories on why people bother to challenge books. I start with the idea that challenging books is a symbolic act. In some ways, it does and does not really do anything. The book is still available. You can get the book lots of different ways. In some ways, it’s entirely symbolic — to say, “We don’t want this book in our library or school.”

But it’s also not symbolic, because you really are impeding access to books. You’re in fact saying that people who can’t afford to buy the book can’t get it. Or in a curriculum, you’re saying, “This is not what I want my kids to learn; they should learn something else.”

Where my religious studies work comes in is really thinking about why is reading so fundamental in our world. And why do we revere books, the codex, so much. I trace this from changes, basically, in Western Christianity, especially through the Reformation.

I start with it in the medieval ages, with the introduction of reading silently, which is not how people read before. Oddly enough, silent reading comes up all the time in book challenges, because you don’t know what people are reading or how they’re interpreting it when they read silently. You can’t interject and say, “I don’t agree with this” or, “This is how you should think about this particular text.”

The Reformation was incredibly important for thinking about how we educate people in our world overall. What happened in the Reformation was basically that the Reformers said that there isn’t anybody between you and your salvation: “If you read this text, you will find out everything you need for salvation.” That is actually so radical. We don’t even think about it, how radical that was at that time — the idea that reading leads to the salvation of your soul.

This is what I still hear from challengers. People will say, “If someone reads this, then there will be a bad outcome.” It’s the idea that there’s something in the text that will change them as a person. I don’t have any other language for talking about it than this religious language. This is often said in secular settings, but when you think about how people think about reading, you can see this tracing through the Reformation.

Also, the book itself — the book is a reifying object. People think that books should have truth, and truth should be in books. I don’t know how you can talk about that without discussing the Bible. There’s this idea that Bibles have truth, the actual object. I only have language from religion, from faith, to talk about how people talk about reading.

F&L: Mainline Protestants may not recognize the issues you raise and how those show up in book banning. They see the practice as sort of this outlier but not necessarily something they would engage in as a person of faith. But a person of faith could see book banning as trying to eliminate voices and faces that are equally beloved by God.

EK: To the question of the diverse books that are being challenged so much right now, to me, this is much more about the continuation of Lost Cause-ism. It is a demand that history be taught in a way that is triumphant and not necessarily truthful. It’s also a sort of privileging of only certain types of people and their responses. Whenever you talk about The 1619 Project, there’s always a [challenge] of, “Kids will get upset.” Which kids? Whose kids?

I’ve realized how many white parents do not talk to their kids about the history of our country; it just does not come up. I got into a long argument with someone talking about book bans, where they said 8 is too young to hear about slavery. I don’t even know how to respond to that. When I was growing up, my Aunt Babe died in 1990 at the age of 104. Her parents were enslaved. It’s not even that far away. My parents grew up in South Carolina during the civil rights era.

It’s really a lack of talking about what people’s true histories are and wanting to sanitize that in ways that do take away people’s humanity. But I also think it removes the people who are making this argument from their humanity, like the idea that you cannot grapple with the terrible things that human beings have done or how different people have lived their lives. You are actually saying, “I’m not able to be in community with my fellow human being.”