The wail of a passing fire engine’s siren drowns out the prayers of about 40 people gathered around a table on a Main Street sidewalk in the bustling college town of Northampton, Mass.

Unfazed, the makeshift congregation incorporates the alarm -- and whatever crisis lies beneath it -- into the petitions they are in the midst of offering: prayers for people in the hospital, for people in the grip of addiction, for a woman’s mother.

“Lord, please stretch out your hands to protect those firefighters, and the people they’re trying to help,” says a young woman wearing an “Assassin’s Creed III” T-shirt.

With that, the worshippers recite the Lord’s Prayer in unison.

It’s Sunday evening at Cathedral in the Night, one of the founding ministries of Clearstory Collective, a network of churches and ministries in western Massachusetts intended for people seeking something other than conventional church worship. Sponsored by the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts, the collective and its members draw on ancient and modern church traditions in an effort to appeal to young people and others who might not otherwise be attracted to church.

Many of the member ministries will be familiar to anyone who follows young adult, collegiate and alternative ministry. The network includes midnight breakfasts for students studying for finals at Smith College and Mount Holyoke College, a monthly Taizé worship service, street ministries, an urban garden, pub theology, an online forum and a website that takes care to distinguish the collective from “the institutional church of the last 1700 years.”

Yet Clearstory Collective is different, because it aims to be more than the sum of its parts, creating a new but very old kind of ministry that helps churches and parachurch organizations collaborate and learn from each other. The collective is doing that not by rejecting institutions altogether, but by striving to create a productive tension within them.

An innovative ancient ministry

“It’s a loose confederation of ecclesias -- literally, from the Greek, ‘assemblies of people’ -- which is an ancient idea,” said the Rev. Chris Carlisle, a campus ministry veteran who spearheaded the creation of the collective. “This is not an innovative new ministry. This is an innovative ancient ministry.”

Carlisle, an Episcopal priest for 30 years -- including 25 as chaplain at the University of Massachusetts -- came up with the idea for Clearstory in 2011, several months after being appointed director of higher education and young adult ministry for the diocese.

Western Massachusetts is thick with college campuses and tens of thousands of students. Even after his many years in campus ministry, Carlisle felt overwhelmed by his new job.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- To what extent does your organization have to act as both “insider” and “outsider?” What tensions does that produce, and how do you navigate them?

- In what ways does your organization operate “out there alone?”

- How could it benefit from being in partnership with others?

- What question does your organization seek to answer? Who is asking it?

“I realized there was no way I could be on 31 campuses at the same time,” Carlisle said. “I had to do something to coalesce the campuses. The Internet was an obvious medium, but I also knew there were a lot of alternative ministries going on in the church that weren’t being recognized.”

One of those ministries was Cathedral in the Night, which Carlisle and other pastors in Northampton founded in January 2011.

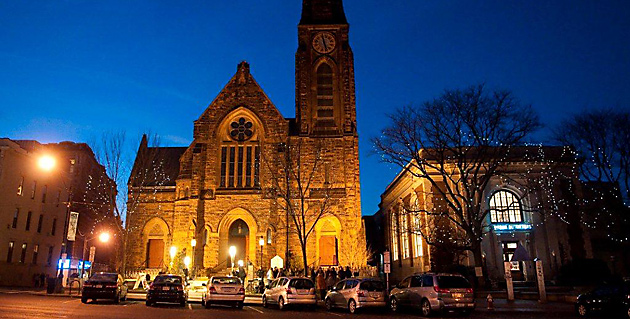

Held every Sunday at 5 p.m., the ministry is an outdoor worship service that draws together students and residents, young and old, people with housing and people without.

Worship concludes with Eucharist and then a full meal, offered to anyone who wants it.

The service is held year-round, rain or shine, in heat or snow. During the dark Massachusetts winters, the cathedral installs “walls” of light, using paper lanterns to create a sense of liturgical space.

“There tends to be, for many reasons, not much attention paid to aesthetics in ministries like this,” Carlisle says. “Our idea for Cathedral in the Night was essentially to create a church with permeable walls.”

Natural fits

In creating the collective, Carlisle hoped both to knit together existing programs -- ministries that were different and appealed to the unchurched -- and to inspire others to create new ones. Church Without Walls, a similar weekly outdoor prayer service in Springfield; the campus breakfasts; and Gideon’s Garden, a parish ministry in Great Barrington that grows fruits and vegetables for area soup kitchens and food pantries, were all natural fits.

The diocese has supported and encouraged the collective from the start, but Carlisle has been careful to maintain some distance between the collective and the more familiar face of the church.

“When you look at Jesus’ criticism of the Pharisees, that’s a criticism of us, of me as a priest,” he says. “That tension is always there. It’s important, actually.”

To that end, Carlisle has resisted efforts, for example, to prominently feature the collective’s website on the main diocesan page.

“The collective has to stand on its own; otherwise, it’s just the same group of people who’d be going to the diocesan website seeing it,” he said.

Given Carlisle's deep Episcopalian roots -- the last time his family wasn’t Anglican, he said, was before the Reformation, and a grandfather was once the bishop of Montreal -- he understands the value of institutional support.

“Jesus conducted his ministry in the streets and in the synagogues,” Carlisle said. “You have to have both. It can’t be either-or.”

The diocese, for its part, is willing to lend whatever help might be requested but understands that Clearstory has to chart its own course, said the Rev. Richard Simpson, who as canon to the ordinary serves as an assistant to Bishop Douglas Fisher.

“We can help to support and nurture this, but by its nature, it’s not just another program the diocese is creating,” Simpson said.

Simpson sees Clearstory as part of a tradition of movements within the larger church, such as those fostered by John Wesley and St. Francis.

“Some of this is innovative, but it’s also a return to our roots,” he said. “Jesus wasn’t building churches. We can get too comfortable being inside our beautiful buildings.”

To that “both-and” rather than “either-or” end, the collective has applied to the Episcopal Church to be designated as a “mission enterprise zone,” a status that recognizes and provides funding and support for creative ministries.

Benefits for members

For members, being part of the collective brings multiple benefits, from the practical to the divine, or at least the theological. In addition to sharing information and learning from one another, members begin to think about church differently, Carlisle said.

The collaboration, for example, cuts across denominational lines. Cathedral in the Night has always been an ecumenical effort, founded and supported by the Episcopal diocese, an ELCA congregation and a Congregational church. And the weekly service is held on property jointly owned by the United Church of Christ and the American Baptist Churches USA.

The Rev. Steven Wilco, pastor of Immanuel Lutheran Church in Amherst, was the presiding pastor on the recent Sunday evening when the firetruck sped by.

“Our congregation benefits from seeing our worship in this context,” Wilco said. “It makes me think about who belongs to the body of Christ in a new way.”

Similarly, being part of the collective gives members a more complex, nuanced face to present to the world, Carlisle said.

“The message that gets sent is that you can be Christian outside the church building and outside Sunday morning,” he said. “But you don’t feel as though you’re out there alone, with nothing to do with the institutional church and tradition.”

Worship at Cathedral in the Night, for example, blends old and new in a way that Carlisle hopes will come to characterize everything about the collective. The service has hymns and prayers for the faithful, the Lord’s Prayer and the distribution of communion.

But it all happens in a public space, with curious passers-by walking around and sometimes through the body of believers. Nearby, on the edge of the crowd, people -- some homeless, some youthful punk rockers, some just hungry -- drift back and forth, waiting for the dinner service.

Jesus’ ministry in the streets

“For me, this adds to the experience of worship,” Wilco said. “We get caught up in the trap of thinking worship is isolated from the rest of the world, forgetting that Jesus carried out his ministry in the streets.”

Even something as familiar and seemingly nonliturgical as the midnight breakfasts at Smith and Mount Holyoke draw on church traditions, Carlisle said. Being in the collective helps remind breakfast participants of that fact.

“That’s unbridled Benedictine hospitality,” he says. “It’s a reincarnation in the 21st century of ancient monastic traditions.”

When people begin thinking about church as something bigger than what happens in a particular building, they also begin to think about church growth differently, Carlisle said. They start to see it not just in terms of their own congregation but in terms of the collective or a geographic area or even the Internet -- what Carlisle likes to call “the electronic diaspora.”

And as word of the collective spreads, other ministries are asking to join.

“This is really getting traction in the diocese,” Carlisle said.

St. John’s Episcopal Church in Williamstown, for example, has been talking with Carlisle about joining.

“Clearstory Collective is trying to tell the story of churches that are aiming out at the world,” said the Rev. Peter Elvin, the rector at St. John’s. “And that’s what we’re doing.”

Williamstown illustrates the kinds of challenges and opportunities that the collective seeks to address. Nestled in the Berkshire Mountains, the town has an abundance of cultural riches such as Williams College, the Clark Art Institute and the annual Williamstown Theatre Festival, which draws thousands to the community every summer.

But alongside the splendor is grinding rural poverty that usually goes overlooked and unmentioned in rhapsodic accounts about the Berkshires. The concentration of resources and population in and around Boston makes the poverty in western Massachusetts even more striking.

“We’ve got issues with food security, with access to health care, with transportation,” Elvin said. “Basically, all the things you find in a sparsely populated county that doesn’t get our fair share of resources from Boston.”

For the past two years, St. John’s has worked to help support and resettle people who lived in a mobile home park that was destroyed by Tropical Storm Irene. Being in the collective would provide opportunities to “cross-fertilize” with other ministries facing the same challenges, share strategies and learn from others, Elvin said.

“We want to learn skills we can use to develop our congregation, as well as learn what works outside our congregation,” he said.

Connected to parish life

That connection to day-to-day parish life is key for the collective and its member ministries, Carlisle said. Ideally, Clearstory will be part of an ongoing learning process both for the individual ministries and for the pastors and campus ministry leaders who participate in them. What people learn at Clearstory can then be taken back to their congregations, and vice versa.

Worcester Fellowship, for example, provides food, Bible study and a eucharistic service outdoors every Sunday in a large, once-industrial city. Carlisle said the fellowship does an excellent job raising up people from the homeless community as leaders, but it can also learn from other collective members.

“A lot of our members can learn from them,” he said. “But they don’t have much of a background in student ministry, and that’s something that Cathedral in the Night, for example, can provide guidance in.”

For now, less than a year after it was founded, the collective is focused on getting the word out and adding like-minded ministries, while awaiting the go-ahead from the Episcopal Church to become an enterprise zone.

But whatever comes, the collective won’t be trying to measure success by metrics alone.

“Numbers are a manifestation rather than a driver,” Carlisle said.

Sure, Cathedral in the Night has grown from a handful of worshippers to 50 to 60 on an average Sunday, with twice that number taking part in the meal afterward. And more parishes and ministries like St. John’s and the Worcester Fellowship have heard about Clearstory and are looking to join.

But those are not important right now.

“The death knell for us is worrying about who’s there, how many this week compared to last week and so on,” he said. “The way to measure our success is to look around and ask, ‘Are we answering a question that anyone’s actually asking?’”