I’m sometimes jealous of those star-following magi we call the wise men. They walk briefly onto the stage of history with one task: pay homage to a newborn king. They have found their vocation, and they pursue it single-mindedly.

Leadership expert Jim Collins would be proud. The magi epitomize what he calls a “hedgehog”: they know one big thing. They’ve discovered what they can do best.

They follow their star.

That’s the prevalent vocational advice we give to both leaders and organizations: Focus. Discover your passion. Live and work at that one intersection “where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet,” as Frederick Buechner famously put it.

I’ve co-authored a book that gives this very advice to declining congregations: discover the one thing you do best, then prune, prune, prune your list of programs and ministries. And I think it’s still good advice.

Most of the time.

Because I know there are leaders who have heeded that advice and yet can’t wrestle their communities into committing to just One Big Thing. Their organizations simply won’t follow just one star. Their tentacles of service and commitment stretch too far.

And at 42, I look at all my efforts to find that one thing -- my one star -- and realize, sadly, that I’m running out of time. I’ll likely never develop a single expertise; my areas of gladness are too diverse for me to acquire complete mastery. I’m condemned to be a generalist, or (as I imagine others call me) a dilettante.

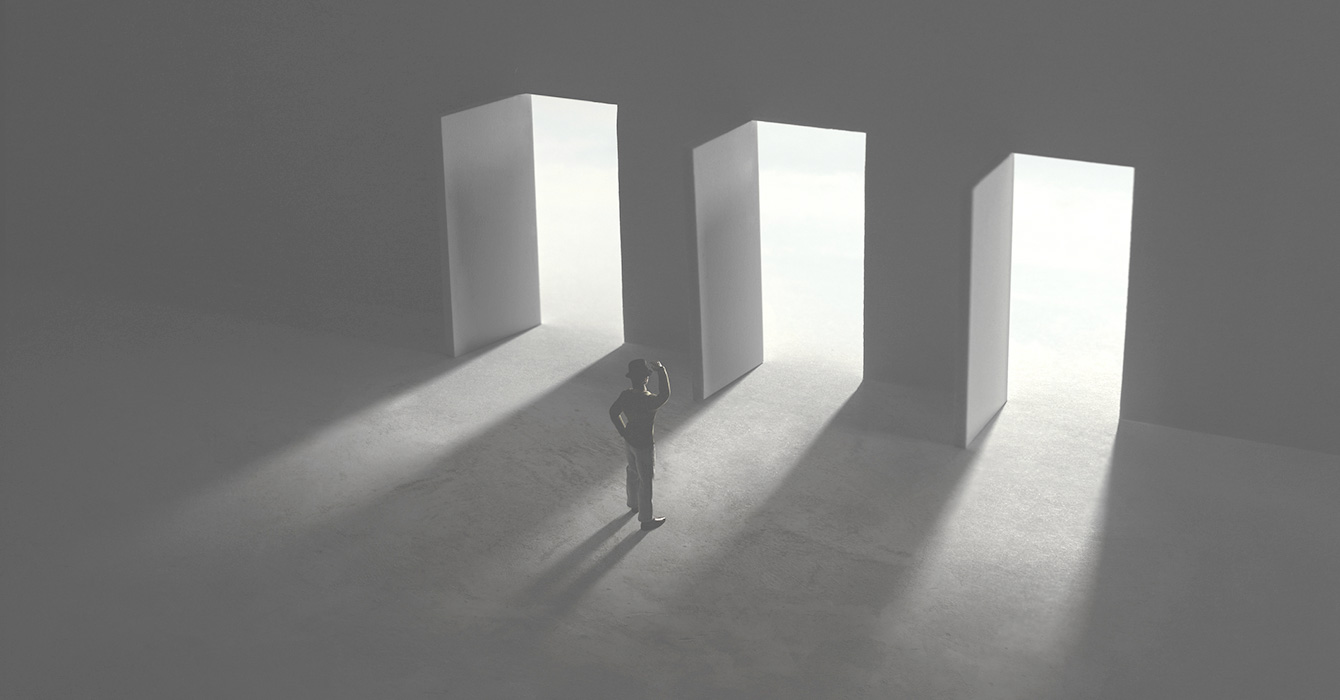

That is, until I consider this one liberating possibility: maybe vocation doesn’t have to be a single star. Maybe for some of us -- leaders and organizations -- vocation will be more like a constellation, several stars forming a coherent image, each star burning bright at different seasons of life.

In that case, discerning vocation lies more in finding the pattern among one’s various gifts, passions and gladnesses and letting each one shine brightly at the right time.

I saw this at work in my own life recently. I left a pedagogy workshop to finish my reading for the course I was taking on spiritual writing but instead turned my attention to my application for a spiritual direction training program. I’m also working on leadership, preaching and spirituality syllabi for my seminary’s new curriculum.

And what I’d really love to pursue -- but don’t have the money for -- is a master of fine arts in creative writing. I have a couple of children’s novels outlined.

When I have this many irons in the fire, I feel the weight of Quaker mystic Thomas Kelly’s judgment from 80 years ago: “Before we know it we are pulled and hauled breathlessly along by an overburdened program of good committees and good undertakings.”

But I take heart when I see others who also have many irons in the fire. I’m thinking of a new missional community in an economically distressed borough near where I live.

Three Thursday nights a month, the community hosts a neighborhood meal. They engage in a ministry of empowerment called Circles out of Poverty. They host legal and health clinics, sublet their space to an adult day care ministry, and stay active in community development. They offer two Bible studies a week, and they worship together each Sunday night.

I can imagine a consultant looking at this community and seeing their energy dissipated in too many directions.

But I see something else: a community committed to discerning what God is up to in the wider neighborhood and joining in. It’s a coherent constellation with several stars, because God seems to be up to quite a lot.

And when I’m being generous, I can see the same in myself. Taken together, my interests outline my overarching joy in helping individuals and communities become open to what God is doing in their lives and respond in faith.

Sometimes I do that through writing, sometimes through teaching, sometimes through speaking, and sometimes through sitting with an individual and helping her discern her vocation -- whether a single star or a constellation.

There is a danger that the image of vocation-as-constellation can be used as an excuse for distracting ourselves from our vocations when they get difficult or boring, when acedia sets in. Individuals and communities should remain mindful of this danger.

But a bigger danger I’ve discovered is that the lure of expertise -- the siren call of specialization, with its promise of both mastery and recognition -- might cause the constellation that is my vocation to become lopsided and eventually unrecognizable.

Sometimes we need to give ourselves the gift of ignoring the conventional wisdom, the gift of allowing ourselves to be guided by a constellation -- many stars that form one picture -- without feeling guilty that our vocations don’t conform to the expectations of others.

They are, after all, our vocations, not someone else’s. And who knows? Maybe I’ll write that children’s novel.