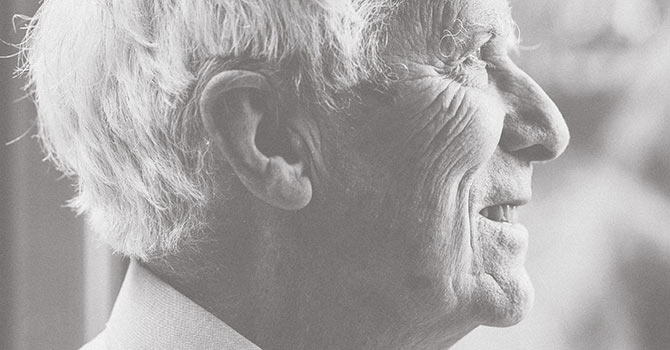

Nicholas Wolterstorff is an eminent American philosophical theologian, writing on such topics as art, Scripture, philosophy of religion and suffering. In 2007, he published “Justice: Rights and Wrongs,” the first volume of a planned two-volume work on justice.

He is Noah Porter Professor Emeritus of Philosophical Theology at Yale Divinity School and taught previously at the Free University in the Netherlands and at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich. A member of the Christian Reformed Church in North America, he currently serves as a senior fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia.

He is Noah Porter Professor Emeritus of Philosophical Theology at Yale Divinity School and taught previously at the Free University in the Netherlands and at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich. A member of the Christian Reformed Church in North America, he currently serves as a senior fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia.

Wolterstorff spoke with Faith & Leadership about vibrant institutions, the necessity for Christian institutions to hear the voices and see the faces of those who suffer, and what he learned from his craftsman grandfather and father about how to do philosophy. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: You’ve written about Christian colleges as institutions that ought to educate for shalom. Why is it important that schools aren’t merely academic but that they contribute to the flourishing of communities around them?

As a young professor at Calvin, I was involved in curricular studies. About two years after I got there, I proposed that the entire curriculum should be revised. I’m astonished to this day that the senior people didn’t just silence this brash newcomer. Instead I became head of a curricular revision committee. It became important for me to figure out what holds a curriculum together. You’ve got sciences and arts and my own passion, justice. What holds it all together? It eventually became clear to me that there is a biblical category of flourishing, of shalom. [It is] “peace” in the New Testament, but eirene in Greek is a pretty weak translation of what the Old Testament means by shalom. It means flourishing.

That’s what a Christian college should be about. Not just planting thoughts in people’s heads and getting them into professional positions but flourishing, in all its dimensions.

Q: Is that a model that churches and other Christian institutions besides colleges can also aim for?

Absolutely. When the Scriptures talk about love, commanding “love your neighbor as yourself,” you may ask, “Well, what’s the goal of this? What’s it after?” It seems to me it seeks the flourishing of your fellow human beings in all dimensions. I had various personal interests: art, justice and so forth. I had to ask how I was going to integrate them. It seemed to me that the category that unites these instead of splitting them apart is the category of shalom. That’s what the gospel is about: how humankind can flourish.

Q: Why is it important that leaders of institutions, who can live pretty sheltered lives, ought to go out of their way to be in touch with humans who suffer?

So, a crucial part of shalom, then, is -- and of seeking shalom -- is justice. You can’t have shalom without justice. I mean, you may con people into thinking that they’re doing okay and so forth but whether they’re conned or not, if they’re suffering from injustice, if they’re being wronged, this is not true shalom. So a crucial part of what Christian institutions should care about in teaching their students and parishioners and so forth to seek shalom is to be alert to the ways in which their neighbors and humankind in general are being wronged, and that’s justice.

So, given that I was sort of plunged into two important issues of justice, being sent to South Africa well before the revolution occurred and getting involved with the Palestinians, and these were eye openers. They were in a classic Protestant sense. They came to me as a call from God. So I had to reflect, then, on why I had been relatively unconcerned with this before, these two situations and others, and why other human beings were, and then it became clear to me that what had happened in my case is that I had read about South Africa and I had read about the Middle East but it was being confronted with the faces and the voices of the suffering. That’s what I found profoundly altering.

And I think that’s true for all of us. It remains an abstraction by and large. Television can help. The pictures of Haiti and so forth are far more effective than just the print in the newspapers. So if a Christian institution, then, is really to seek justice, it has to somehow find a way to have those voices and see those faces, either by going there or having them come to you or whatever.

Q: I’m struck by the Reformed tradition’s particular gift of being articulate about institutions: why they should be founded and tended and what good they bear in the world.

I think that is true. I’m not exactly sure why it’s true, but the Reformed tradition certainly has always had a more institutional character to it than just individuals. I was reared to think of the church and not just a bunch of Christian people getting together. The health of institutions -- educational institutions, ecclesiastical institutions, institutions of all sorts -- has been a crucial part of the tradition.

Growing up in the Americanized version of the Dutch Reformed tradition, you absorb the idea that being loyal to and supportive of institutions is a fundamental Christian responsibility. The loyalty involves criticizing them. We’re pretty good at holding their feet to the fire. But the sense that institutions are alien or the enemy is very foreign. I hear Americans talking about government with suspicion, as the enemy. This is so alien to my tradition. You hold the feet of the politicians to the fire, but you don’t regard them as the enemy.

Q: Even with the cases of injustice that were so formative for you, in South Africa and Palestine?

That’s right. It’s got to be reformed. You don’t get rid of government, but you reform it.

Q: Much of your recent work has been devoted to art. For you, institutions make artistic ability and craftsmanship possible.

In the arts there is the romantic vision of a teenager having poetry inside. They go up to their attic and start writing poetry or composing songs. It almost never happens that way. Instead, we have long traditions of poetry writing and reading, and long traditions of musical composition. Young students have to get inducted into those traditions and not think they’re doing it all by themselves.

Perhaps there are a few cases of folk artists who have not had teachers but have picked it up. They’re really the exceptions. These practices require institutions where students learn how to read and write poetry and music.

Q: In your observation, what makes for faithful and successful leadership?

A good leader has to tap into the aspirations of the people that he or she is leading. They cannot just impose, but have to listen, find out what people aspire toward, and then put those aspirations together. They enhance some aspirations, criticize others, then coordinate in such a way that people will feel that they own this vision. Then the leader has to figure out ways of getting there.

Leaders of course are always tempted to do it differently. They find their institutions unruly, so they attempt to forget about the aspirations of the members of the institution and just impose their own rules, so it follows their vision, or even more minimally they try to make it less unruly.

It’s crucial that the leader find language that everybody can own and say, “This is indeed what we’re after.” We may not have even realized that this is what we were after. The leader will listen to more than just the sheer words of what people are saying but to the undertone. They must listen to everybody. There will always be some talkative people in the group. But they must listen not only to the talkative people but also to the ones who sit off to the side and don’t say anything.

Q: Why is craft important to you?

I grew up in a family of craftsmen. My grandfather was a cabinetmaker in Utrecht, the Netherlands. I still have some of his hand tools. My father was a woodworker. They were both professionals. I’ve done it on the side. All my sons do it. It’s in our genes.

My father was very odd in that he wasn’t in it for financial success. I put it like this sometimes: When financial success threatened, he succeeded in averting it. People needed cabinetry, and he loved the wood. He loved different kinds of wood so he’d collect all kinds of exotic woods and use them in various ways. I can still see him yet, rubbing his hands on the wood. I learned from him reverence for wood, letting the wood talk back to you as it were. Wood at some point says, “Look, I don’t want you to do this to me. You’re violating me. I wasn’t meant to be treated in this way.” I learned from him the craftsmanship to make it right and not to cut corners.

Later, when I tried to explain to students how to write a philosophy paper, I’d use the metaphor of craftsmanship. A good philosophy paper has some ideas but it also needs craftsmanship. You can’t just ooze big ideas. I would say, “The dados have to be tight.” I’d see the students looking around at each other as if to say, “Dados?” “The dovetailing has to be tight.” “Dovetails?” So I eliminated that. Well, I first tried to explain the metaphor and that got too complicated. Craftsmanship became for me an image for how philosophy papers ought to be written.

Q: You taught with a remarkable group of faculty at Calvin: Alvin Plantinga, Richard Mouw. What was it about the institution that made it possible for your department’s work to be better than the sum of its parts?

In the late ’40s, early ’50s when I went to college, we had some charismatic philosophy teachers, Harry Jellema, Henry Stob. They didn’t write much, but they taught us to see the importance of philosophy. It was not just a game. It featured more than little techniques. So when I and my colleagues Al and Rich were together at Calvin in the ’60s and ’70s, we met every Tuesday afternoon almost through the entire year. We got the registrar never to schedule any courses for us from 2 to 4 on Tuesdays. We all participated in a discussion always about our own work, not about somebody else’s work, always handed out in advance. It was tough love.

We’d go through these papers. The strategy was to ask whether anybody wanted to talk about the main structure of the paper. Then we’d go through page by page. It was a blend of “Do you have an idea here?” and “Let’s tend to the craftsmanship of page 3. You didn’t put it quite right here.” What made it possible was that we were in different academic areas. We liked each other. We were all Christians engaged in a common project of doing philosophy. None of us was a prima donna.

When I went to Yale, people would say to me, “Why don’t you reproduce it?” I thought about that for awhile. It became perfectly clear to me within six months that that was impossible. Yale was filled with prima donnas. They’re not willing to read somebody else’s work unless it directly pertains to their own -- not a ghost of a chance. You could have discussions. It was congenial. But it was not collegial in the same sense.

Q: What else did Yale teach you about institutions of theological education?

I’d never taught in a divinity school. I’d never been a student in a divinity school. I had thought that they were either flakey or oppressive. Yale was neither.

At Yale, as at most theological institutions, they have a four-fold division of academic areas. Area 4 is where they do the practical things like teaching, preaching and liturgy. It became clear to me immediately that there was a pecking order. Area 4 was at the bottom. In the other three areas -- Bible, theology and church history -- you learn the important things and in Area 4 you merely apply them. This just irritated me.

Then I read a book by a Belgian monk, Jean Leclercq, “The Love of Learning and Desire for God,” about learning in medieval monasteries. I knew medieval philosophy but nothing about the monastic tradition. It occurred to me that this was an alternative theological tradition. Call it “formation theology:” theology shaped by the need to give guidance and formation to a certain community, the monastic community in Bernard of Clairvaux’s case. But once you open yourself up to this notion of formation, then you see that the church fathers were in good measure doing this. Calvin was. He never had a university position but he’s dealing with this unruly city of refugees in Geneva. Gustavo Gutierrez in Lima, Peru, is doing formation theology. He doesn’t teach in a university but he’s got these poor people in Lima he’s responsible for. There’s a long, rich theological tradition here, an alternative one to most options on offer.

It would be really interesting for seminaries to explore calling this “application” material “formation theology.” We’ll read what Bernard said to his monks and what Calvin said to Genevans and what Gutierrez says to Limans. And we’ll ask ourselves how we can appropriate what we’ve learned to leading a city, leading a congregation in downtown Chicago, and the formation of the entire community. It would be really interesting for some seminary somewhere to see whether this goes anywhere.