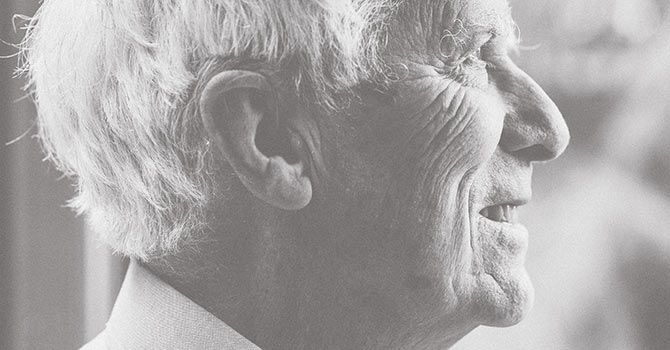

Nicholas Wolterstorff describes his life as gratitude and sorrow intertwined.

In his new memoir, “In This World of Wonders: Memoir of a Life in Learning,” Wolterstorff writes about his idyllic childhood in rural Minnesota and the passing of his mother, as well as his illustrious career as a philosopher at Calvin and Yale and the death of his son.

“It has been a wonderful walk through the world,” Wolterstorff said. “But it hasn't all been wonder.”

He describes the good fortune that brought him into prominence as Christian philosophy’s face and the personal experiences that have transformed his thought, including multiple trips to apartheid South Africa and the death of his son Eric.

Grief changes how you experience the world, Wolterstorff said. But it does not remove the wonder.

“Grief led me to see God and the world differently -- better,” he said.

Wolterstorff, who retired from teaching in 2002, is the Noah Porter Professor Emeritus of Philosophical Theology at Yale Divinity School. He helped found the Society of Christian Philosophers with Alvin Plantinga in 1978 and was the Gifford Lecturer at St. Andrews in 1995.

Wolterstorff, who retired from teaching in 2002, is the Noah Porter Professor Emeritus of Philosophical Theology at Yale Divinity School. He helped found the Society of Christian Philosophers with Alvin Plantinga in 1978 and was the Gifford Lecturer at St. Andrews in 1995.

He has published dozens of books, including “Art in Action,” “Justice in Love” and “Lament for a Son.”

Wolterstorff spoke with Faith & Leadership about his memoir and the experiences behind it. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: There have been significant moments of pain in your life. How do you maintain belief that ours is indeed a “world of wonders”?

It has been a wonderful walk through the world. When I was a kid, I never would have anticipated the wonder of plants growing, of children, of family, of my wife, of art, of Hans Wegner chairs. It’s been a world of -- and a life of -- wonder and love.

But it hasn’t all been wonder.

The death of Eric, our son, at 25 years old, was extremely painful. The grief of it is still there; it never quite disappears. Grief led me to see God and the world differently -- better. So a fuller title would indeed have been “In This World of Wonders and Grief,” but that would not have been a good title.

Q: You have never discussed “Lament for a Son” in a university classroom, but you describe discussing the book with men in prison as the most moving teaching experience of your entire life. Why was this so significant?

I often hear that the book is discussed in a course. I've never been invited to participate in such a course, but I think I would turn down the invitation if I got it, because I fear that the discussion in these courses goes like this: “What is Professor Wolterstorff's view of grief? Do you agree with his view of grief? What is his view of God in this? Do you agree?” and so forth. And I would find that just painful. And sort of objectivizing.

What happened in this experience of being invited to talk about the book in a prison was something I didn't anticipate.

There were middle-aged guys in their 40s, and 17 of the 20 were in there for life. I initially didn't know why I was feeling so many emotions as I watched them discuss the book.

But then it hit me after 10 minutes. These guys had their books open, referring to and reading passages to each other, and then it occurred to me, “Oh, I see what's going on! They're not reading this book as Nick Wolterstorff's lament; they're reading it as their lament!”

When they'd quote a passage, they would immediately speak about the murder of their best friend or the assault on their wife. These people took my words to express their own grief, grief over the many ways that life has been lost. Seeing this in person was so extraordinary and moving.

Though I call the memoir “In This World of Wonders,” Eric's death divided my life into two parts: before and after.

It was huge. A death like that -- of a child, of a friend, of a relative -- creates a huge hole in your life that you slowly learn to live around.

So I couldn't talk about the important episodes of my life without talking about this gap and how it happened and how I gradually had to learn to live around it.

What was so meaningful about the honor of attending that class was that these guys were taking my words and using them to talk about the gaps in their lives, finding some way to live with the grief of lost life.

Q: Your book title not only talks about wonder, but it talks about “a life in learning.” What do you mean by that?

I wanted to get across two things. It’s been a life inside learning, as it were -- not just looking at it from the outside but inside -- but also a life engaged with learning. It seemed to me “in” captured those two ideas better. I don’t just think about learning, but it’s a life inside of learning.

Q: What do you hope that the audience will take from reading the memoir?

I hope that they will take from it why philosophy is significant, how it fits into this person’s life, how it arises out of this person's life. How matters that confronted me provoke me into reflecting philosophically on certain issues.

And I hope they take from it that toward the end of my life, I lived it with a sense of deep gratitude for what it has been.

Q: In the book, you mention the astounding fact that you never applied for an academic position. What has changed in theological education over your time as a professor?

I lived, from my standpoint, in a golden era. I wasn't invited by Yale to apply for a position in the philosophy department but was offered a position. I wasn't invited by Calvin to apply for a position in the philosophy department but was offered a position. And when I moved back to Yale after 30 years at Calvin, they came asking me to apply. I didn't apply, but I still got the job.

But I don't like saying this loudly, because I recognize that it was a golden age and the age is over -- and that there was an “old boys’ network" at work, which excluded many people.

But in my last years at Yale, students would graduate and they'd apply to 20 different places or whatever. Some would not get hired for a couple of years, some would get a long succession of one-year stints, and so forth. So it's a different era.

Q: What do you think students, especially seminary students, need to be learning?

They’ve got to learn the standard stuff: they’ve got to learn biblical exegesis, history of Christianity, church history, theology and so forth.

But I think in the midst of it all, they have to learn to listen. To listen to the challenges and inspirations that come their way, not to have such a predetermined agenda that they just plow ahead on their own path.

I guess if I were giving a talk to seminary students, I would tell them to first learn the traditional stuff and then be open.

Q: You were involved in civil rights marches and feminism in the ‘60s, but you name a transformation that occurred when you heard and saw protestors against apartheid in South Africa. Why were those voices and faces so important?

For most people, including myself, being involved in the struggle to correct injustice requires emotional engagement. For most people, information is not enough.

What I emphasize in the memoir is the emotion of empathy when I was in South Africa and listening to the people of color talk about what the system of apartheid was doing to them. I heard these people of color and saw the injustice and their anger.

I've come to think that the struggle against injustice has to have an emotional component, and the two most foundational emotions are probably empathy with the victims and anger at the perpetrators.

One might mount a legitimate criticism of me and say, “But why didn’t you get more engaged by the civil rights struggle, by the struggle for the rights of women, the Vietnam War, in the same way? Why didn’t your emotions get engaged then?”

I don’t have any good answer to that except that I didn’t, in quite the same direct way, see the faces and hear the voices. So it’s not a justification but an explanation.

Q: In this context, you talk about how documentary film and fiction operate differently from other communication, such as journalism. What is the difference there?

For those who want to lead some movement to correct some form of injustice, it is important to get supporters in the public. Information alone is not enough, but you have to present live faces and voices -- or faces and voices on film or in novels or dramas -- to achieve emotional engagement.

A good friend of mine, Jeffrey Stout, has a wonderful book, “Blessed Are the Organized,” in which he talks about different episodes in which the organizers quite explicitly engaged the emotions of both the victims and the public. I think that's a good model.

Martha Nussbaum suggested that fiction and film invite others to imagine what it's like to be that kind of person. You get a good deal of that when you just sit and look at people's faces and listen to their stories. Journalism gives us the facts of the case, and sometimes it can sort of report feelings, but it doesn’t invite us to imagine in the same way.

I suppose a great example is Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom's Cabin.” I talk a bit about that in another little book of mine, “Journey toward Justice.” This piece of fiction played a huge role in the abolitionist movement in the 19th century. Lincoln was reported to have said when he met Stowe, “Are you the little woman who started this big war?”

Hearing stories invites someone to imagine what it was like to be a person of color in South Africa. That’s what happened to me. I had quite a bit of information about South Africa before I went there, but nothing like listening to their stories invited me to imagine what it was like to be them.