The first time I brought my gringo husband home to meet my Cuban parents, my mom served him spicy oxtail stew, rabo encendido (“tail on fire”). It was her test.

We still laugh about that dinner, how he lifted the bones to his mouth to suck off the tender meat, rising to the challenge.

The next day, she pulled it out of the refrigerator.

“Mira la sustancia!” she marveled as she saw the jellied stew broth. “Es para levantar un muerto!” meaning it was so nourishing, it could raise a dead person back to life.

As a Christian leader and educator, I want to believe as passionately that what we offer in our meals helps us do life-giving work. These days, as we are reexamining our offerings, evaluating them for inclusivity, anti-racism and justice, I wonder how to lift undocumented food workers to our consciousness, particularly our brothers and sisters who process our meat.

Living and working among meatpackers in Omaha, Nebraska, for many years, I came to understand the dangers of their working conditions and how many of them live with insecure (or no) immigration status.

More recently, the reality of the estimated 188,000 immigrant meat and poultry workers has been highlighted, especially since April 28, when President Donald Trump issued an executive order deeming meat and poultry processors “critical infrastructure” in the food supply chain and barring more facilities from closing despite the rapid spread of COVID-19.

In one instance, children of workers organized to protest the lack of protective equipment, testing and paid sick leave in those facilities, speaking out for parents whose lack of stable immigration status made it dangerous for them to speak out for themselves.

Meatpacking requires human workers. The dangers on the kill floor and the processing lines cannot be outsourced to robots, because the varying sizes and shapes of the large animals require the perception of human eyes and the precision of human hands wielding knives and hooks.

Once one of the highest-paid jobs in U.S. manufacturing, meatpacking has become less reliant on specific, marketable skills. Its focus is on maximizing efficiency and profit on a rapid assembly line in an increasingly consolidated and union-averse industry.

Immigrants, who are less likely to complain about conditions, are recruited at the borders and in areas of the country experiencing high refugee resettlement. They are promised steady work where little English is needed for their hazardous, relentless responsibilities.

For me, this is a personal concern as well as one of faith-based and civic responsibility. Close friends, the parents of our goddaughter, Brisa, work in large meatpacking plants in Omaha. (In our Latinx Catholic tradition, we became family -- compadres -- when my husband and I sponsored Brisa at her baptism.)

They have shared with me that workers at one plant were offered small bonuses not to miss shifts during COVID-19. Those at another were given meat to take home. At neither were employees supplied with PPE for weeks, and many fell ill.

These friends own their own home, pay taxes and contribute to Social Security and Medicare, even though they will not benefit from either because of their immigration status. They have two children who are citizens and one who is in this country under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

For 19 years, they have been renewing their temporary protected status every 18 months -- a process that includes background checks -- in order to remain in the United States legally.

They are among 195,000 Salvadoran recipients of TPS given for humanitarian reasons. Along with other “TPSers” (or “tepesianos,” as my friends refer to themselves) from Honduras, Haiti, Sudan, Nicaragua and Nepal, they are among the most vetted of all immigrants in this country.

They may now lose their work and their home and be separated from their children through deportation. TPS is subject to the determination of the executive branch, and their status has been revoked by this administration. More than 317,000 TPSers with an estimated 250,000 citizen children are subject to deportation next year, barring Senate action.

The pandemic and the greater unveiling of our systemic racial injustices have prompted contemplation and self-examination of our responsibilities. I am asking myself new questions.

How do I as a Christian leader bring to collective consciousness the exclusion of the workers who cut our meat without a secure place at our table of plenty?

How can justice be restored for these who have labored with the ongoing fearful trauma of family separation while contributing essential work at tremendous cost to their own bodies?

Today, 34 years since the passage of the last immigration reform that offered a path to citizenship for so many of what we now call “essential workers,” is immigration reform part of the work of reparation to which we are called?

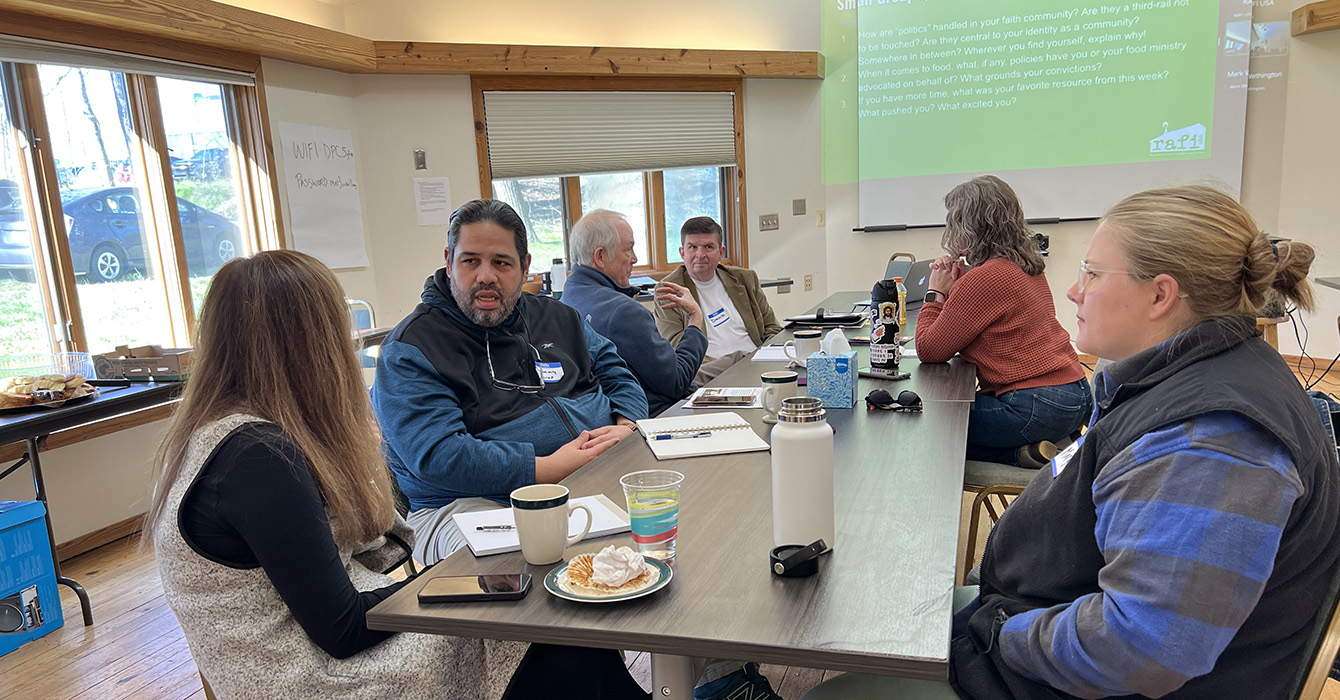

Can we bring these issues into our leadership development curricula explicitly and implicitly so that our meal sharing is more Eucharistic, more inclusive of those who provision our “secure” table in their great insecurity? Leadership Education, for example, has engaged local culinary artists to prepare meals for some of our programs.

When we return to in-person programming that requires meals to be served, how do we find a way to include consciousness of the precarity of these brothers and sisters in our implicit and explicit curriculum?

Can we make even our meal offerings an invitation for solidarity and strengthening for the work of justice and a sign of the resurrection?

How do we extend our Christian contribution so we all have a secure table?

I bought an oxtail recently at the Durham Farmers’ Market. I felt good about buying directly from local farmers who had raised the animal for 18 months in a nearby town. Some even consider purchasing from local farmers a political act, as it tangibly supports a more sustainable alternative to our industrialized food system.

Yet I ask myself, “Is this enough?” We have to do more.