Beginning in January, a group made up primarily of strangers met on Zoom to share sacred stories at the intersection of food and faith. By the eighth and final session four months into Come to the Table’s School for Food Justice, Faith and Storytelling, the learning was clear.

“This cohort helped me think outside the box of food,” one participant said.

These faith leaders joined SFJFS for a common reason — nearly half of U.S. faith communities have or support a food ministry of some kind, yet food security and food access have not been significantly improving. Outside of federal assistance food programs, nonprofit organizations, often aligned with churches, are where many people experiencing food insecurity turn for help supplying their refrigerators and cupboards.

If faith communities are a major player in alleviating hunger, it makes sense that they can serve as more than distributors of food; they can be a key part of the solution to food insecurity. Rather than implicitly hoping only to relieve immediate hunger, faith communities can and should work at the root of the issue, with hopes of ending hunger and rendering food pantries obsolete.

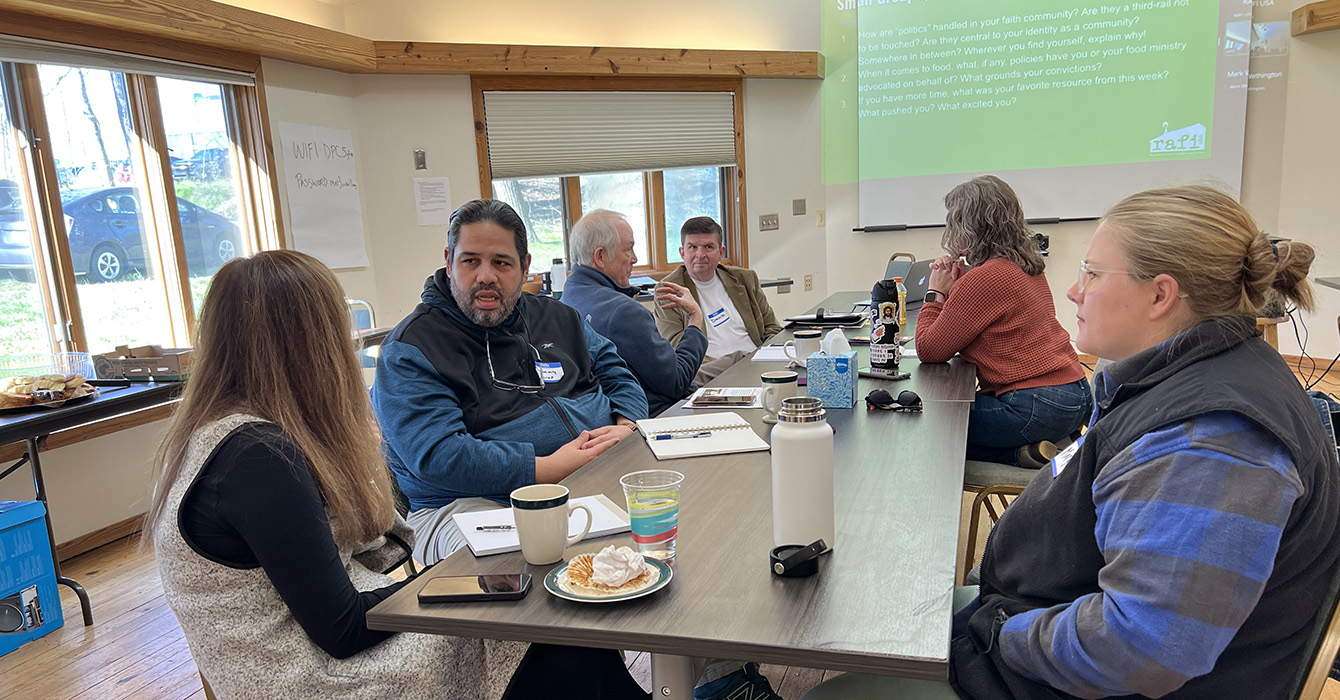

In Come to the Table’s SFJFS, a cohort of faith leaders meets to learn about and articulate a new story about food injustice and the practical change required to offer new and creative solutions to hunger in participants’ communities.

The first half of the 2023 cohort’s training asked the question, “What is the problem?” and tackled issues such as food insecurity, lack of food access, the state of farming in America and corporate consolidation. These first sessions were led by RAFI-USA staff, with featured presenters including Mark Yaconelli, the author of “Between the Listening and the Telling: How Stories Can Save Us.”

The history and current state of farmers of color in America stuck with participants. The session focused on not just the data behind racial land loss but the stories of discrimination that led to massive declines in the number of farmers of color and amount of farmland owned. It included how churches can partner with farmers of color.

“The session that challenged me the most and was the most enlightening was the unit on farmers of color,” the Rev. Tom Greener said. Greener, a Methodist pastor from Greenville, North Carolina, referenced the substantial drop-off in farmers of color in the U.S. over the last century.

“You can’t go from 14% to 1.4% just from natural attrition. It has to happen intentionally, and that profound injustice really resonated with me,” he said.

After Greener took what he had learned back to St. James UMC, where he is senior pastor, the congregation decided to partner with a local farmer of color to start a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program.

“I feel more equipped to address the anti-racism issues within food systems,” Greener said. “To be able to show that to folks and be able to offer them a concrete means through a partnership that we are developing that they can embrace a form of anti-racism has been very helpful.”

The first few sessions led to the understanding that food ministries require broadening our thinking about food and examining deeper issues in the food landscape, including who has access and what food they have access to.

“Most of the churches I know … are pretty good at ‘collecting and donating’ but have a harder time looking deeper into the causes that seem to necessitate such ministries," said the Rev. Amy Vaughan, a pastor in western North Carolina. “I would like to make it a little clearer for people to understand how to get at the root causes instead of treating the symptoms only.”

The remaining sessions led participants to faithfully imagine how they could make change in their communities. Discussions centered on how churches could engage with those they serve to build power, expand partnerships in their communities and advocate for policies that would positively affect food-insecure families.

In a session on public theology, author and activist Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove challenged participants to consider what it could look like for churches to serve in their communities as organizers for moral change.

“Christian social engagement has to be different than simply deciding what you think the outcome needs to be and then finding your way to the position of greatest influence to make that happen,” Wilson-Hartgrove said. “Jesus organizes people who are directly impacted in such a way that they have hope that something else is possible.”

“I found it very impactful to hear we [as faith leaders] have the power, especially working together, to make a difference,” participant P.J. Spinillo said. “No one’s going to turn the angle 90 degrees overnight on their own, but together we can turn it.”

SFJFS also led to fresh observations about often-overlooked stories in Scripture that speak to our present moment.

“Scripture might reveal new truths if we are willing to try new ways of looking at it — it is sacred but not fragile,” a participant said. “Scripture that never challenges us as individuals and as communities is a dead reading that never liberates or leads to flourishing.”

Throughout the eight sessions, story was centered as a way to communicate truths about food. Not only does everyone have a story to tell, but communities and attitudes are shaped by stories that themselves have the power to either empower or disempower. Future cohorts are taking shape for those interested in learning more.

Sociologist and author Sarah Bowen challenged faith leaders to listen to the stories of the communities they serve, reminding participants that true food justice starts by “understand[ing] people and communities and building on their ideas.”

Aaron Johnson, RAFI’s program manager for the Challenging Corporate Power program, told the group that faith leaders’ superpower is their ability to shape narratives patiently in their communities around the forces and power dynamics that are at work in the food system. Using the metaphor of a garden, Johnson suggested that pastors are in the unique position of deciding which narratives get weeded out and which get watered and tended to.

Because every session included storytelling opportunities, space for faithful imagination and resource sharing, participants become tightly connected.

“This group has been my church,” one participant said.

If faith communities are a major player in alleviating hunger, it makes sense that they can serve as more than distributors of food; they can be a key part of the solution to food insecurity.