When the seeds of the North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies (now NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community) were taking root in the 1990s in Canada, becoming an accredited graduate school seemed like a far-off goal. The group of Indigenous scholars began having conversations, which blossomed into an annual symposium, an academic journal and graduate curricula.

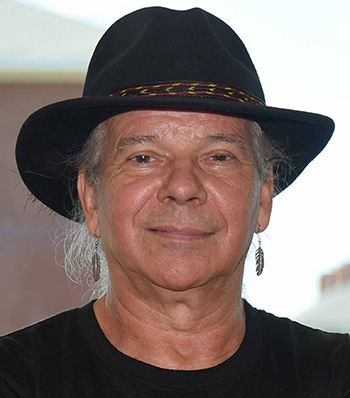

“But when we held our first symposium, I don’t think any of us imagined that we might want to, never mind get to that point,” co-founder Terry LeBlanc said.

It wasn’t the main objective for NAIITS to receive formal ATS (Association of Theological Schools) accreditation, but when it did arrive in spring 2021, LeBlanc says it felt “vindicating.”

NAIITS is the only accredited Indigenous-led graduate theological school in North America. It offers four master’s degrees, together with an experimental accredited Ph.D. program.

LeBlanc is CEO and director of Indigenous Pathways, a corporate entity comprising NAIITS and its sister organization, iEmergence, which focuses on leadership development in Indigenous and tribal communities. He completed his Ph.D. at Asbury Theological Seminary.

LeBlanc spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about NAIITS’ accomplishments so far and what the future might look like for the school. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Can you tell me the story of NAIITS?

Terry LeBlanc: The idea of it began back in the late ’80s for some of us, mid-’90s for others, and came about as a result of the continuing challenges raised by varieties of individuals in the Christian church, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, who criticized the idea that Indigenous culture and faith could be brought together in some fashion — or put another way, that one could be authentically Indigenous and authentically Christian in the same way that one could be authentically Euro-American or Euro-Canadian Christian.

So it began with conversations about how to address that, which led to hosting annual symposia on Indigenous theology and mission, which in turn led to the publication of a journal and the creation of a faculty and curriculum to teach our own programs in the broad compass of divinity.

F&L: Recently, you were accredited by ATS. How did that feel?

TL: Vindicating. I’m not sure that we had it in mind when we launched our formal programs, first in Canada in the late 1990s and then in the U.S. in 2001. But when we held our first symposium, I don’t think any of us imagined that we might want to, never mind get to that point.

F&L: What kinds of degrees do you offer?

TL: We offer four master’s degrees in North America: an M.A. in intercultural studies, an M.T.S., an M.A. in Indigenous community development and a newly framed M.Div. program. We also offer an experimental Ph.D. program accredited by ATS.

And in Australia, we offer an M.T.S. program, along with a grad certificate and a grad diploma, as well as the Ph.D.

F&L: How does the teaching work, with so many different people from so many different places?

TL: We had determined that we needed to do something to address the issue of many Indigenous students being reluctant to leave their home communities or territories to go for lengthy periods of time to study. So we had already determined that we needed to offer some of our programming in a virtual format, online within learning management software, as well as with Zoom and virtual videoconferencing.

But we also wanted to be sure that we created an in-person community experience, so we went to a trimester system, with two semesters, the September and January semesters, being offered in a virtual format, synchronous and asynchronous, and then the summer semester, which wrapped around our annual symposium on Indigenous theology and mission, being offered as an in-person intensive set of courses.

We’ve been doing that from the beginning, so going virtual with COVID wasn’t an issue for us.

F&L: What have you seen your students be able to do with their training in their communities?

TL: Varieties of things. Some have gone into spiritual care work as chaplains, some, in urban environments, doing street work or urban-based advocacy and ministry. Some have gone into pastoral ministry.

Others have become or are becoming community scholars in their communities or have gone on to do further study to advance their academic skills.

All of the graduates thus far have gone into vocations that connect to the disciplines within which they received their degrees.

F&L: Why is NAIITS so important?

TL: At this juncture, it’s important because it’s the only Indigenous-designed, developed, delivered, and wholly governed Indigenous graduate and postgraduate theological educational institution that is ATS-accredited in North America.

While there are other institutions teaching at the undergraduate level, and some at the graduate level, they are either teaching under the auspices of non-Indigenous governance or teaching under the auspices of other denomination-institutional environments.

NAIITS is unique, and that in itself makes it essential, since to be able to govern our own theological education, albeit within the parameters that ATS and the new standards of accreditation require, is critically important for us to advance our notion that one can be authentically Indigenous and authentically Christian.

F&L: In terms of the governance being Indigenous, how does that make the education qualitatively different for your students?

TL: Well, you could have the same course title, say New Testament Introduction. Offered from a Euro-Canadian or Euro-American seminary or divinity college, it will use mostly standard approaches to New Testament study, even though some will be more contemporary than others. They’ll use materials that are largely written by or taken from a Western philosophical and hermeneutical approach.

Whereas a New Testament introduction course that we offer will come from an Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous ontology and worldview and will use Indigenous frame materials, in addition to individuals from the Indigenous community who come in to provide community perspectives.

When we do a course, irrespective of what the course may be, it’s offered from an Indigenous perspective as the first order of business, not as a supplement.

F&L: How does theological education that is done by and driven by Indigenous people avoid some of the blind spots for the traditional Euro-American-centric theological education?

TL: Well, whether intended or not, by default, given the trajectory of the Western church, Euro-American as well as Euro-Canadian and Australian (or wherever it may be) approaches to theology have largely assumed that a singular worldview is the appropriate worldview through which to approach the Scriptures, through which to approach the ideas, the principal ideas of Christian faith and life.

As a consequence, this theology is not only blind in certain areas but oblivious to the fact that Christianity, or Christian faith — or, if you will, the following of Jesus — doesn’t originate in the Western environment.

There’s an imposed notion that Jesus was an American or Jesus was a Canadian, and the images, of course, tend to bear out the Eurocentric nature of Christianity down through the centuries.

There’s also certainly the idea that a theology rooted in the Western Enlightenment is an engagement with faith that provides a context for science and faith to coexist. And yet, at the same time, it doesn’t provide a place or a context where that coexistence can have a mutuality about it; it’s more that there are boundaries between the two, and on occasion, there are semipermeable membranes — but on other occasions, they’re completely separate.

Whereas with an Indigenous context, there is not an either/or epistemology at play but rather a both/and, so that impacts how we view not only the text of the Christian Scriptures but also other stories of experience and tradition of the pursuit of God.

F&L: What do you think the future looks like for NAIITS?

TL: Oh, goodness, I wish I were good at prognostication. Given that we’ll celebrate 25 years next year, and seeing what we’re able to accomplish with our partnerships and support, I foresee greater numbers of partnerships of differing sorts.

I can certainly see us creating perhaps a chair of Indigenous studies, which will have a Christian framework available for study but won’t be specifically a theological chair. It will be a chair of Indigenous studies that neither excludes nor centers Christian faith but rather sees Christian faith as one aspect of Indigenous life throughout our history.

F&L: Speaking of the partnerships, how can people who aren’t Indigenous support or partner with Indigenous theological development?

TL: Our partnerships with existing non-Indigenous institutions have been extremely supportive and beneficial.

We do provide up to 25% of our seats in any given degree program or course for non-Indigenous students — first, for non-Indigenous students who are engaged with Indigenous community, and then second, for non-Indigenous students who are wanting a non-Western approach to theological education.

Certainly financially, where we’re a not-for-profit, we are essentially people-funded. We’re tuition- and fundraising-driven — not that that isn’t the case for many other institutions — but we have a constituency that, as you might imagine, given the history of Christianity in treating Indigenous peoples, aren’t necessarily at the top of the list for Indigenous peoples support, and through no fault of our own.