Chris Winans was in trouble.

It was a frigid afternoon in February 2021, and Winans, the senior pastor of Cornerstone Evangelical Presbyterian Church, sat down across from me in a booth at the Brighton Bar and Grill. It’s a comfortable little haunt on Main Street in my hometown, backing up to a wooden playground and a mill pond. But Winans didn’t look comfortable. He looked panicked, even a bit paranoid, glancing around him as we began to speak. Soon, I would understand why.

Dad [who had led the church for twenty-six years] had spent years looking for an heir apparent. Several associate pastors had come and gone. Cornerstone was his life’s work — he had led the church throughout virtually its entire history — so there would be no settling in his search for a successor. The uncertainty wore him down. Dad worried he might never find the right guy. And then one day, while attending a denominational meeting, he met a young associate pastor from Goodwill EPC — the very church where he’d been saved, and where he’d worked his first job out of seminary. The pastor’s name was Chris Winans. Dad hired him away from Goodwill to lead a young adults ministry at Cornerstone, and from the moment Winans arrived, I could tell he was the one.

Barely thirty years old, Winans looked to be exactly what Cornerstone needed in its next generation of leadership. He was a brilliant student of the scriptures. He spoke with precision and clarity from the pulpit. He had a humble, easygoing way about him, operating without the outsize ego that often accompanies first-rate preaching. Everything about this young pastor — the boyish sweep of brown hair, his delightful young family — seemed to be straight out of central casting.

There was just one problem: Chris Winans was not a conservative Republican. He didn’t like guns. He cared more about funding poverty programs than cutting tax rates. He had no appetite for the unrepentant antics of President Donald Trump. Of course, none of this would seem heretical to Christians in other parts of the world; given his staunch pro-life position, Winans would in most places be considered an archetype of spiritual and intellectual consistency. But in the American evangelical tradition, and at a church like Cornerstone, the whiff of liberalism made him suspect.

Brighton, Michigan, is a bubble within a bubble. The surrounding county, Livingston, is the most reliably Republican-voting jurisdiction in the state. For the last three decades, anyone looking to escape the high crime of Detroit and the high costs of its contiguous counties headed west to Livingston, and, if they could afford it, to the quiet little burg of Brighton. The town is deeply conservative, deceptively wealthy, and almost exclusively white. Its biggest church, Cornerstone, became a microcosm of the surrounding area. There was no meaningful diversity inside the church — ethnically, culturally, or politically — until Winans came to town.

Dad knew the guy was different. A trained musician, Winans liked to play piano instead of sports, and had no taste for hunting or fishing. Frankly, Dad thought that was a bonus. Winans wasn’t supposed to simply placate Cornerstone’s aging base of wealthy, white congregants. The new pastor’s charge was to evangelize, to cast a vision and expand the mission field, to challenge those inside the church and carry the gospel to those outside it. Dad didn’t think there was undue risk. He felt confident that his hand-chosen successor’s gifts in the pulpit, and his manifest love of Jesus, would be more than sufficient to smooth over any bumps in the transition.

He was wrong. Almost immediately after Winans moved into the role of senior pastor, at the beginning of 2018, the knives came out. Any errant remark he made about politics or culture, any slight of Trump or the Republican Party — real or perceived — invited a torrent of criticism. Longtime members would demand a meeting with Dad, who had stayed on in a support role, and unload on Winans. Dad would ask if there was any substantive criticism of the theology; almost invariably, the answer was no. A month into the job, when Winans remarked in a sermon that Christians ought to be protective of God’s creation — arguing for congregants to take seriously the threats to the planet — the dam nearly burst. People came to Dad by the dozens, outraged, demanding that Winans be reined in. Dad told them all to get lost. If anyone had a beef with the senior pastor, he said, they needed to take it up with the senior pastor. (Dad did so himself, buying Winans lunch at Chili’s and suggesting he tone down the tree hugging.)

It was a tumultuous first year on the job, but Winans survived it. He tightened the screws and checked his ideological impulses, realizing that his good intentions had gotten the better of him. The people at Cornerstone were in a period of adjustment. He needed to respect that — and he needed to adjust, too. As long as Dad was in his corner, Winans knew he would be okay.

And then Dad died.

Eighteen months later, as we sat together picking at hot sandwiches, I was starting to understand the dismay I’d seen on his face at the funeral. Winans told me that he was barely hanging on at Cornerstone. The church had become unruly; his job had become unbearable. It wasn’t long after Dad died — making Winans the unquestioned leader of the church — that the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. In the vortex of fear and uncertainty, Michigan’s Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer, issued sweeping shutdown orders that implicated houses of worship. Churches everywhere had to choose: Obey the government and close for a period of time, or violate the orders and remain open. Winans felt it was a no-brainer. Whitmer wasn’t ordering Christians to do something sinful or immoral or unholy. Scripture says to respect governing authorities, so that’s what Cornerstone would do.

The decision didn’t go over well. Some in his congregation swore that the virus was a hoax cooked up by globalist elites who wanted to control the population; others merely believed that church was too important — too “essential,” in the parlance of the times — to be shuttered for any reason, ever. What these groups shared was a prophetic certainty, promulgated by the evangelical movement for decades, that godless Democrats would one day launch a frontal assault on Christianity in America. This belief wasn’t limited to Pentecostals and their so-called charismatic spiritual practices, or to fringe fundamentalists, or to Dominionists, the nascent hard-liners who seek to merge church and state under biblical law. No, this was accepted dogma for conservative Christians of every tribe and affiliation. And it was only a matter of time, they knew, until secularists weaponized the government to eradicate the Almighty from public life.

In the spring of 2020, that prophecy was being fulfilled — and weak, spineless pastors like Chris Winans were letting it happen.

When Cornerstone reopened after several weeks of online Sunday worship, a chunk of the congregation was missing. The numbers dwindled further in the months ahead. As debates over shutdowns gave way to disagreements over masking and social distancing, more and more people left the church, believing their new pastor was being too deferential to government health guidelines.

Winans was reeling — and the ground beneath him was about to get a whole lot shakier. In May 2020, an unarmed Black man named George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis by a policeman who knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes as he gasped, “I can’t breathe.” The incident sparked a summer of unrest: Protests for racial justice and scattered outbreaks of violent rioting prompted millions of Americans to pick sides, writing social media posts and putting up yard signs that invariably alienated neighbors, family members, and fellow churchgoers.

Turbocharging the chaos was Trump’s campaign for reelection. The sitting president of the United States was adamant that Democrats were plotting to rig the contest against him, and he made clear that the ramifications of this reached beyond electoral politics. Trump had campaigned in 2016 on a promise that “Christianity will have power” if he won the White House; now he warned that his opponent in the 2020 election, former vice president Joe Biden, was going to “hurt God” and target Christians for their religious beliefs. Embracing dark rhetoric and violent conspiracy theories, the president seized upon notions of America’s prophesied apocalypse, enlisting leading evangelicals to help frame a cosmic spiritual clash between the God-fearing Republicans who supported Trump and the secular leftists who viewed the forty-fifth president as the last obstacle standing between them and a conquest of America’s Judeo-Christian ethos.

The consequences were real and devastating. People at Cornerstone began confronting their pastor, demanding that he speak out against government mandates and Black Lives Matter and Joe Biden. When Winans declined, more people left. The mood soured noticeably after Trump’s defeat in November 2020. A crusade to overturn the election result, led by a group of outspoken Christians — including Trump lawyer Jenna Ellis, who was later censured by a judge after admitting to spreading numerous lies about election fraud, and author Eric Metaxas, who told fellow believers that martyrdom might be required to keep Trump in office — roiled the Cornerstone congregation. A popular church leader was fired after it was discovered that she had been proselytizing for QAnon, the far-right online religion that depicts Trump as a messianic figure battling a satanic cabal of elites who cannibalize children for sustenance. When the church dismissed her, without announcing why, the departures came in droves. Some of those abandoning Cornerstone were not core congregants. But plenty of them were. They were people who served in leadership roles, people Winans counted as confidants and personal friends. ...

Winans asked me to keep something between us: He was thinking about leaving Cornerstone. The “psychological onslaught,” he said, had become too much. Recently, he’d developed a form of anxiety disorder and had to retreat into a dark room between services to collect himself. After talking with his father, a physician, Winans met with several trusted elders, shared his illness, and asked them to stick close on Sunday mornings so they could catch him if he were to faint and fall over.

I thought about Dad and how heartbroken he would be. Then I started to wonder if Dad didn’t have some level of culpability in all of this. Clearly, long before COVID-19 or George Floyd or Donald Trump, something had gone wrong at Cornerstone. I had always shrugged off the crude, hysterical, sky-is-falling Facebook posts I would see from people at the church. I had found it amusing, if not particularly alarming, that some longtime Cornerstone members were obsessed with trolling me on Twitter. Now I couldn’t help but think these were warnings — bright red blinking lights — that should have been taken seriously. My dad never had a social media account. Did he have any idea just how lost some of his sheep really were?

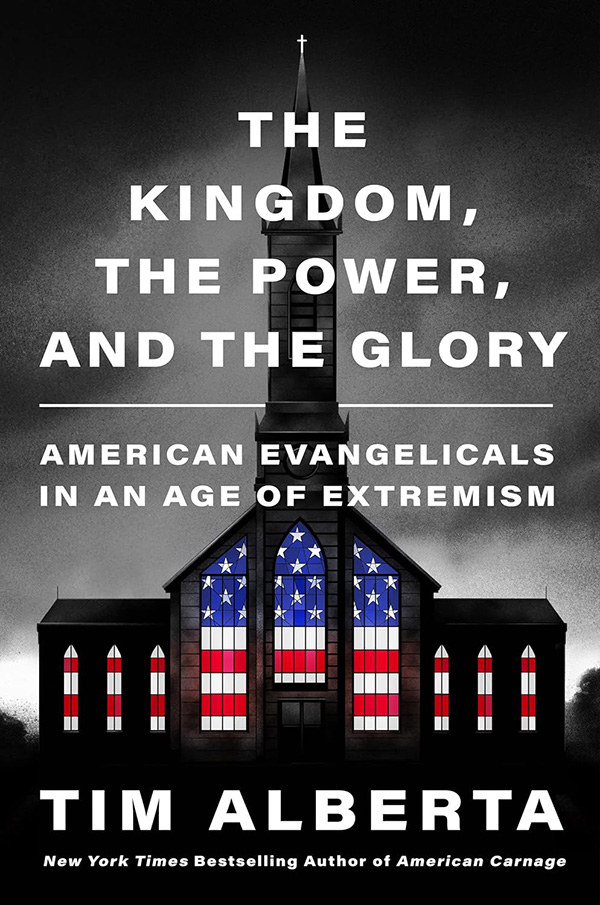

From the book “The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism” by Tim Alberta. Copyright © 2023 by Timothy Alberta. Published by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpted by permission.