In February, Tom Parker, the chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, made abundantly clear to the nation that the rationale underpinning arguments for fetal personhood are explicitly Christian in their origin.

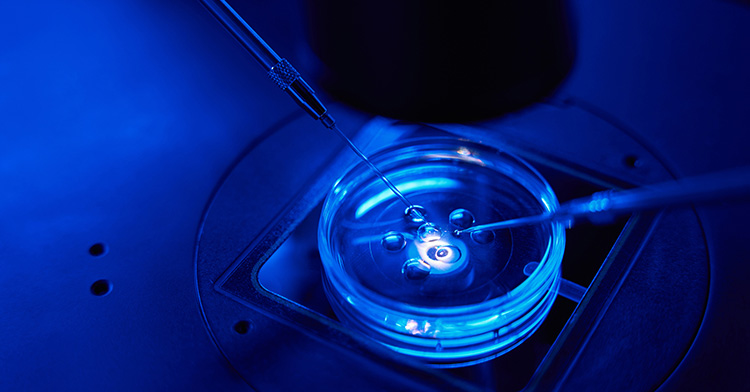

The case hinged on the accidental destruction of frozen embryos that three different couples were storing at a fertility clinic in Alabama. While the lawsuits that followed made several claims, what ultimately caught the nation’s attention was the ruling that those frozen embryos were children and thus deserved legal protection under Alabama’s 1872 Wrongful Death of a Minor Act.

Language matters. It not only reflects how we think about a topic; it shapes the public debate and our own creative capacity to think about and understand an issue. This is particularly true in the public conversation about abortion, where emotionally loaded terms like “unborn baby” are pitted against the clinically accurate but largely unused terms “embryo” and “fetus.”

In Alabama, the ruling not only wrongly equated frozen embryos with children; it also ran counter to what Americans across the country believe about in vitro fertilization. Only 12% of U.S. adults think IVF is morally wrong, and a majority believe that health insurance should cover fertility treatment. Support for fertility treatment is consistent with the fact that a majority of Americans also support the legal right to abortion.

While the Alabama Supreme Court laid bare how clearly both questions revolve around religious beliefs about when life begins, the American public’s support for IVF and abortion access fundamentally reflects shared value in helping people have some measure of control over their fertility. This includes in Alabama, where only 12% of people think abortion should be illegal in all cases.

The strategy of securing legal rights for prenates developed immediately after Roe v. Wade as anti-abortion Christians sought to codify their religious belief that a prenate — a term for the developing entity as long as it resides inside a woman’s body — is a person. This position is most often supported by the theological argument that life or personhood begins at conception.

I believe there are important moral questions about IVF and about abortion, including questions about how we think about the status of the prenate. But these questions are theological and need to be discussed within the context of faith communities, not in courthouses or legislative sessions.

For Christians, beliefs about when life begins range from the moment of conception to the moment of the first breath. And while it is the case that evangelical Christians and Roman Catholic clergy hold extreme positions on the issue of when life begins, their beliefs are not shared by the majority of Christians or by members of other religious traditions.

Establishing legal rights for prenates has been strengthening for decades as states have passed laws related to causing a miscarriage (intentionally or unintentionally) in order to increase the severity of the crime of harming pregnant women. While protecting pregnant women is a noble and just cause, the veiled intention of these bills is evident in that they are often used to prosecute pregnant women for their miscarriages rather than to protect them.

The logic of marking fertilized eggs as beings that hold human rights and deserve legal protection is also the logic that undergirds the near-total abortion bans that exist in 14 states, including eight Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas and West Virginia). Any belief that a fertilized egg is qualitatively the same as a newborn baby can only lead to the kind of ruling that we saw in Alabama where Justice Parker declared by fiat that fertilized eggs are children.

In writing for the majority, Parker argued that the people of Alabama have adopted a “theologically based view of the sanctity of life,” a position he supports by quoting the Bible, the 17th-century Dutch theologian Petrus van Mastricht, Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin to argue that the Ten Commandments’ prohibition against murder is rooted in the theological belief that human beings bear the image of God (imago Dei).

To see this kind of argument in my field — Christian ethics — is par for the course, but to see it in a legal ruling as support for the codification of human rights for a fertilized egg was truly astonishing. Not surprisingly, it drew outrage across the country.

The debate about the moral status of the prenate has been polarized into a false binary between a secular position that defines the prenate as tissue with no moral worth and an anti-abortion Christian position that identifies the prenate as a baby or unborn baby. For many people of faith, neither of these positions rings true. Many Christians do not believe that ending a pregnancy is morally insignificant, but neither do they believe it is murder.

It is possible to recognize that the prenate holds value because it possesses the potential for life without declaring that the prenate is a baby. It is possible to value the prenate and value the pregnant person, and to value them differently. It is possible to destroy embryos in an ethically responsible IVF process, just as it is possible to end pregnancies for morally good reasons.

...these questions are theological and need to be discussed within the context of faith communities, not in courthouses or legislative sessions.