Rachel Kroh didn’t expect that people would respond so strongly to her printmaking.

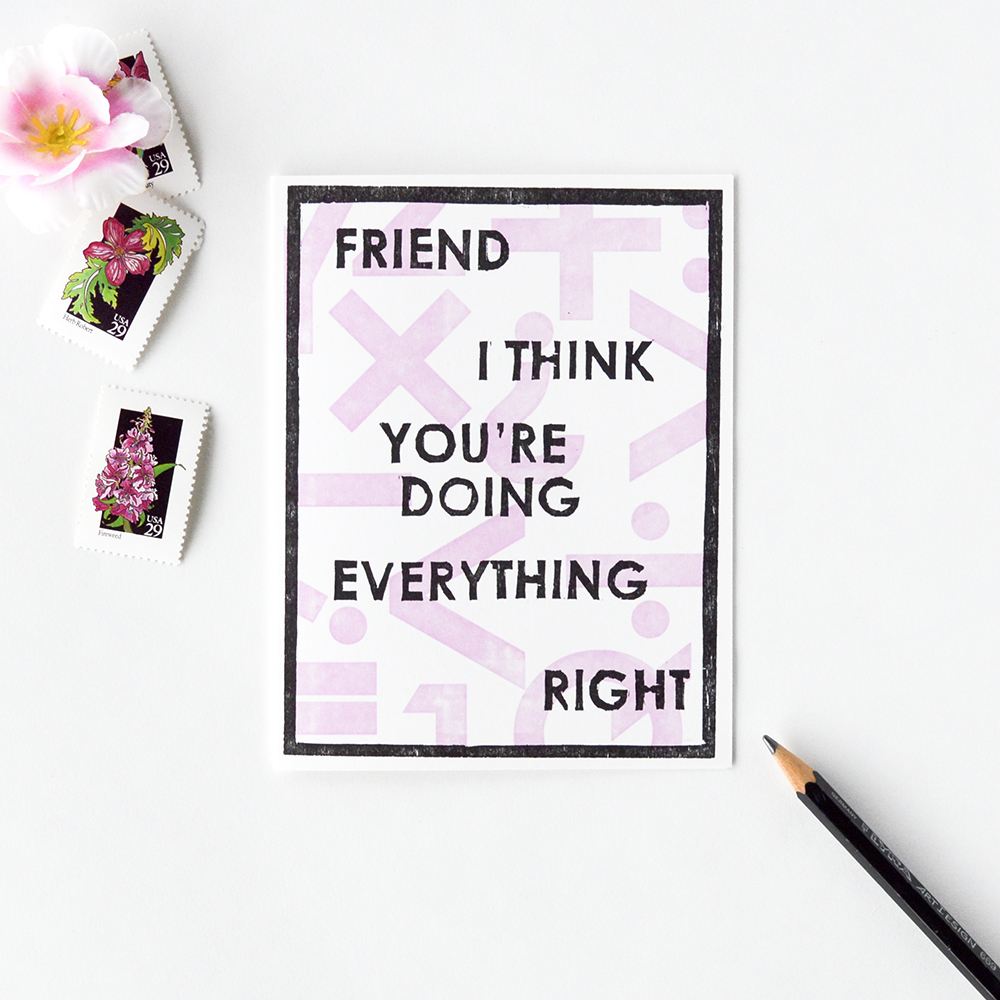

At St. Lydia’s, the dinner church she co-founded, she saw that her prints were a nice way to welcome people and tell them they belonged, through the cards she made and the images she posted on the church website. But the more people resonated with her designs, the more she took the practice seriously as something that could be a full-time business.

Then, after her mother was diagnosed with cancer, Kroh found a hole in the availability of commercial cards she could send that captured the grief of the situation with both the levity and the grace she felt her relationship with her mother deserved.

To communicate her deep love for her mother, Kroh began leaning on the same art practice she’d used to communicate welcome at St. Lydia’s.

From these experiences, and after significant research developing a collection of prints, Kroh founded Heartell Press in New York in 2014. Two years later, she moved the business to Indiana, where it is now located.

She sees her business as a means to help people connect with one another and be present for one another in both bright and dark circumstances.

“If I have something to give, I think this is the medium where I can do it,” she said.

Kroh has a master of arts and religion from Yale Divinity School and a degree in print media from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

She spoke about Heartell Press and its relationship with her own faith journey with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: What’s the story of Heartell Press?

Rachel Kroh: I was living in New York, and I had been working at St. Lydia’s for a few years at that point. I’m one of the founders of St. Lydia’s, with Emily Scott. She was the pastor and founder, and I was the community coordinator for the first five years.

My mom was diagnosed with cancer in 2012 and was living in Utah at the time. I was in New York City, so I went back to visit whenever I could for as long as I could, but in between, I wanted to send cards to her.

But I really couldn’t find the kind of cards that I wanted to send. All the sympathy cards were either a little too cold or distant or formal to send to your mom, someone you talk to every day, or they were the kind of messages like “get well soon,” “it will get better,” “hang in there,” “it’s going to be fine.”

When my mom was diagnosed, they didn’t think she was going to make it past a year. It really wasn’t going to be fine, and there really wasn’t any reason to believe that she was going to get better soon.

There were a few cards that used humor to kind of keep it a little more real, but even that didn’t feel appropriate for who my mom was and who I was at that time and how we were feeling about the whole situation, because my mom getting sick was really just a profound loss from the beginning, even before she died.

So I started making cards for her. I had been making prints since college, and I had gotten a degree in printmaking at the Art Institute of Chicago. I had a studio and was building an art practice there.

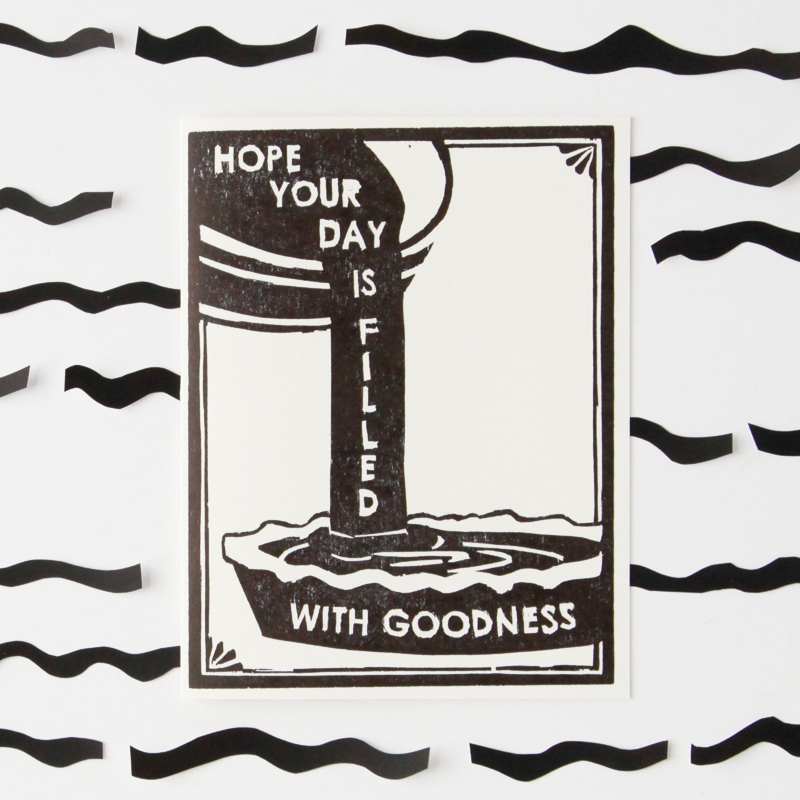

I was mainly painting for galleries, but I was also using woodblock prints to make stuff for St. Lydia’s, and the people at St. Lydia’s really were responding to what I was making. Woodblock prints just felt like the right medium for the kind of thing I wanted to say to my mom, something that was sort of raw. I wanted it to feel immediate, like I had my hands on it and then a moment later it was going to be in her hands. So I started making things for her.

Then people started asking me about the cards and the prints that they were based on, and I wondered if maybe there was a market for them.

It took me a couple of years before I did my first trade show. And then there were a couple more years between when I started making my stuff and when I really started doing it as a business full time.

I think Heartell has become a way for me to process my experience and participate in the world in the way that I want to.

F&L: How has your faith background influenced your work at Heartell?

RK: My faith grew as St. Lydia’s grew. I don’t have a Christian background. I was raised Unitarian and am part of a Unitarian church now. The Unitarian Church was a big part of our lives, especially when I was really little. Fast forward to when I was in college — I was in New York, and the first day of my sophomore year was 9/11. It was a really scary time, and it was the first really big loss that I had experienced.

During that year, we had a guest professor in my Russian literature class who talked about the role of Christianity in these novels that we were reading, and it was the first time I had ever had anyone really break it down, what the Christian faith was about.

The way the professor put it was that there was this whole community of people who had decided to live their lives according to the idea that love is stronger than death, and it made a big impression on me.

I was thinking a lot about death because of 9/11. It was both my first big experience with death and also tied up so intrinsically in the idea of religion and the idea of faith groups and the ways those kinds of ideology can shape your worldview and decide your behavior.

I started studying religion formally in school, and my interest led me to Yale Divinity School. It was my experience at Yale Divinity School that led me to be part of St. Lydia’s.

St. Lydia’s was a project I was able to participate in because it was a creative enterprise for me. It helped me approach the Scriptures and Christian practice and the sacraments in a creative way and to see them as practices much like my creative practices — ways to understand the world, ways to connect with other people, and ways to connect with the best part of ourselves or the quiet stillness that can teach us about the most lasting and solid parts of what being human is about.

I think that experience of gathering with people every Sunday and sharing a meal and all the practical challenges that went along with it — I was doing that at the same time that I was building my art practice, and they just really became tied up for me, the two ways of being in the world.

When I started making those cards, they were definitely informed by the experience I had of meeting all these strangers and meeting them where they were. People brought all of their experience to church every Sunday, and I was basically the “mother hen” of church. I would be the first person people met when they came in the door, and I was the last one there at night.

I was trying to make people feel comfortable. Many of them told me a lot of stories while they were there, and some of them were really suffering. Everyone goes through hard times, but church is one of the places that you go to confront those parts of life and yourself, and I learned a lot about how to just be present with people in those experiences.

Our culture really is not great at being with people who are suffering. All our language around it is very distancing. When you say, “I’m sorry for your loss” — which is a very standard thing to say, and it can be comforting — but it says, “This is your loss, and I’m sorry that you are experiencing this right now.”

We have a hard time just letting people be in pain, and St. Lydia’s taught me a lot about that.

We also did a lot with poetry and songs, and I think just being around all that language really helped me when I was looking for words to put on the cards. I wanted to find words that could bring warmth, presence, understanding and connection without having to do any explaining, fixing, solving or distancing that a lot of our language around loss centers on in everyday culture.

F&L: Why do you have a category of prints called Art for Change?

RK: Social justice was another big piece of what drew me to Christian practice, so I really wanted there to be a part of Heartell Press that is working to make the world better, that believes and acts like we can make a different kind of world than the one we live in now.

All the profits from those prints go toward a different organization every quarter, and we’ve decided to focus on organizations that support people who are starting businesses or running businesses from backgrounds that have been disenfranchised, like Black business owners, female business owners, LGBTQ business owners.

Then the prints themselves also have more of a political touch than the rest of the Heartell catalog. I love having a way to respond more immediately to whatever is happening. With the wholesale line, it just takes a long time to develop those products, and the Art for Change line is a way to get things out there. I try not to be quite as fussy about the details with that line.

F&L: What are some of your favorite prints that you’ve made at Heartell?

RK: Honestly, the first Heartell collection was 10 cards, and some of those are still my favorites. The one that says, “It comes in waves” is a favorite, and there’s a yellow one that says, “Sending you light.” I love those early cards, because I was in such a raw place myself when I designed them, and I think those cards really consolidated all the feelings that I was having and all the hope that I had for how they would ease my mom’s suffering and other people’s suffering.

More recently, there’s one that says, “In my heart and on my mind,” and it has pink cornflowers on it. That one, and there’s one that says, “So very loved” that has some lilies of the valley. Those are ones that I send a lot.

F&L: Do you have any advice for people who are looking to design commercially successful, aesthetically beautiful and emotionally intelligent things?

RK: I think my best advice is just to start, and keep learning. I think the best thing to do is just spend some time working on your practice, give yourself a deadline, create some things, and then put them out there, and you’ll learn by how people respond to what you’re doing.

When I started Heartell, I was really focused on my paintings at that point in my life, but I noticed that people were really responding to the prints instead. Listening to that and having the experience of trying different things and seeing what worked for people is what led me to where I am now.

The thing you think you’re best at may not actually be what the world needs from you. There’s a lot of listening that needs to happen in order to be successful, and the only way to do that is to give people something to respond to.

Don’t get too caught up in planning. Just get in there and start working.