When the Rev. Alexia Salvatierra suggested that a Christian justice conference meeting in San Diego allow young adults working with her to lead the group on its immersion trip to Tijuana, she was disappointed by the pushback she received.

Some felt that because the young people had grown up in the United States, they weren’t knowledgeable enough about Mexico. Others felt that white leaders would be more accessible to some members of the group than the young people whose families emigrated from Latin America.

But by the end of the visit south of the U.S.-Mexico border about five years ago, it was clear to attendees that these young people had something special to offer as leaders.

Salvatierra recalled standing in line to cross back at the San Ysidro Port of Entry and watching a woman from the Midwest, far from the border, approach one of them. The woman thanked the young person for changing the narrative in her understanding of who could lead.

“She said, ‘You changed my life today,’” Salvatierra said. “She said, ‘You changed the hero.’”

According to Salvatierra, that young person responded, “I never saw myself as a hero before.”

These young people who led that visit call themselves puentes, or bridges, because they straddle cultures, languages and faith traditions. Many emigrated from Latin America at an early age with their parents and grew up in the United States. Others were born here and raised by immigrant parents. They understand the culture of their parents, and they understand the culture in the country they now call home.

Knowing each side, they are able to connect people who might otherwise struggle to understand each other. They play crucial roles in helping older immigrant generations communicate with those born in the U.S., as well as in bringing understanding between immigrant and non-immigrant congregations.

But that work can also be emotionally and spiritually taxing.

“Bridges are stepped on. Bridges are walked on,” said Sandy Ovalle Martínez, a co-founder of Puentes Collective. “They’re meant to sustain. They’re meant to connect, but that also means they require a lot of strength, and they’re often not thought about.”

After working as a group within Salvatierra’s organization Matthew 25, which connects immigrant and non-immigrant churches in the movement for immigrant rights, several of the young leaders realized they needed their own space to heal and to grow, independent from the larger organization.

They began Puentes Collective as its own nonprofit officially last year, hosting retreats and other events where puentes can connect and explore their faith and spiritual traditions. The spaces they create honor both sides of their identities.

“What does it look like to honor my Christian faith and reconnect with my Indigenous practices and ancestry?” asked Ovalle Martínez. “That’s what Puentes [Collective] came to do. How do we decolonize the Christian faith as we know it and get in touch with the things that had been called evil or had been demonized?”

Connecting cultures

Growing up, Gabriel Lopez, who is a pastor and co-founder of Puentes Collective, felt disconnected from both Mexican and U.S. culture.

What does it look like to decolonize your faith?

“For a really long time, growing up in the Latino church, being an immigrant, I always felt ‘ni de aquí, ni de allá,’” Lopez said, using a common expression to describe feeling neither from here nor from there.

He felt that he’d been cursed to not fit in anywhere. But he has learned that what his identity has given him are gifts that can be uniquely helpful in spiritual and social justice settings.

As the Trump administration worked to increase deportations of undocumented immigrants and restrict asylum seekers’ ability to request protection, more non-immigrant churches moved to get involved in immigrant rights work.

Organizations such as Southern California’s Matthew 25 helped those churches understand what was already being done in the movement and helped bring them into the efforts. According to Salvatierra, who has been involved since the sanctuary movement of the 1980s, “bridges” like Lopez have been indispensable for making those connections.

“I felt very strongly that what you needed was a partnership of peers between immigrant and non-immigrant people who had something deeply in common, who were standing on common sacred ground, so they could identify with each other,” Salvatierra said. “The best way to create that sacred ground was not just common beliefs but common mission. If people were working together on something they believed was a core part of their faith, they began to trust each other.”

Since 2018, the younger leaders have been offering educational tours of the borderlands to churches and religious conferences. Some visit places like San Diego’s Chicano Park, where the local Mexican American community took a stand against state plans to construct a California Highway Patrol office and instead created a park with murals that today are recognized as a national landmark. Others travel to Tijuana to meet the Mexican churches supporting asylum seekers and receiving deportees.

Where can you come alongside the efforts of others to make a contribution rather than starting something new?

“Our role was to be guides,” said Vanessa Martínez Soltero, a co-founder of Puentes Collective and its current board chair. “Initially, it was to fill the gap of bicultural communication, but also ministry into what are ways in which we can honor people and not just see them as victims or recipients but being able to see them in their full humanity.”

As guides, the puentes found themselves drawing on skills they’ve developed throughout their lives, said Lopez.

“We’ve been translating since we were very young — very important documents for our parents,” Lopez said. “We translate in church. We translate at the store. But then we noticed that we translate more than language. We also translate culture.

“It’s really a gift, because translating just in language doesn’t always translate well. Sometimes there will be something lost. You need somebody from both cultures, and that’s what Puentes is, really. We are able to walk people from one side to another.”

The puentes offer bilingual events, helping monolingual English speakers and monolingual Spanish speakers experience the same spaces and find understanding.

Martínez Soltero said it comes naturally to her.

“Personally, I speak a lot of Spanglish,” she said. “I can move in between those two spaces culturally and linguistically.”

But the bridging work of the puentes goes much further than language and culture. It also requires bridging generational gaps.

Bridging generations

The puentes have learned to embrace their space between first- and second-generation immigrants as well.

Lopez said he first heard the idea of the 1.5 immigrant generation from a Korean church describing its members born in Korea but raised in the United States. He remembered wishing at the time that he had something similar, as someone who emigrated from Mexico as a child. Through the creation of Puentes Collective, he has found that.

Now, it helps him bridge the generations in the church where he pastors.

“Latino churches have been traditionally more conservative in their stance, at least for the immigrant generation, the older generation,” Lopez said. “The younger generations tend to be more progressive, which sometimes makes church difficult, and what we have seen is that a lot of younger Christians in the Latino church, they leave church.”

He says that by having conversations with people of these different generations without trying to change them, he is able to help them understand other generations of the church.

That was true even with his own father, who was also a pastor. Lopez noticed in conversations that his father was defensive at first until he understood that Lopez wasn’t trying to change his mind but rather walk alongside him.

“When he became open to walking [with us], then he started understanding the younger generations in our church and understanding the changes that needed to happen in our church so that we could serve them better,” Lopez said.

How is your church helping bridge different generations of people in your community?

Each of the Puentes co-founders emphasized the importance of honoring elders and ancestors while making space to evolve their own beliefs and practices in ways that make sense for their identities.

“A lot of the conversation, at least for Puentes, is what are the ways in which we honor our elders, in which we honor the struggle and the resilience of our ancestors with the understanding that we’re also individual people,” Martínez Soltero said.

In practice, that includes having advisers like Salvatierra, whom the puentes affectionately call madrina, or godmother.

“I think it’s really encouraging to be able to be generative in that way, to be able to pass on the stories, pass on the wisdom,” Salvatierra said. “We’re not good in this country at passing on movement history, and because of that, people often reinvent the wheel.”

Sometimes elders participate in Puentes' events. Ovalle Martínez planned to have her mother at an upcoming retreat.

How do you create conversations with the goal of understanding rather than change?

“Their presence is stabilizing,” Ovalle Martínez said. “Their presence also brings up the questions. It’s demanding of answers. For many of them, it may be uncomfortable, but what we have found is they have also been deeply nourished as they engage.”

Healing into the future

For Martínez Soltero, maintaining a dialogue between generations and exploring ancestral practices are essential to healing for puentes like her.

“A lot of our elders, particularly immigrant parents who are first generation, there were a lot of sacrifices and cultural sacrifices they felt needed to be done for our generation in order for us to be able to survive in a country that doesn’t want them, that doesn’t recognize their full humanity all the time,” she said. “How do we hold in the tension or live in the tension instead of rejecting everything our elders and ancestors have done because all they were trying to do was survive?”

Many of the puentes, including Martínez Soltero and Ovalle Martínez, have added Indigenous ancestral spiritual traditions into their practices in order to reconnect with some of what was lost for their parents’ generation.

Ovalle Martínez said she began a Zoom group during the pandemic to work through a book called “Voices From the Ancestors: Xicanx and Latinx Spiritual Expressions and Healing Practices.” The goal was more than discussion — it was to do embodied practice. Now some of those practices are included in Puentes Collective retreats.

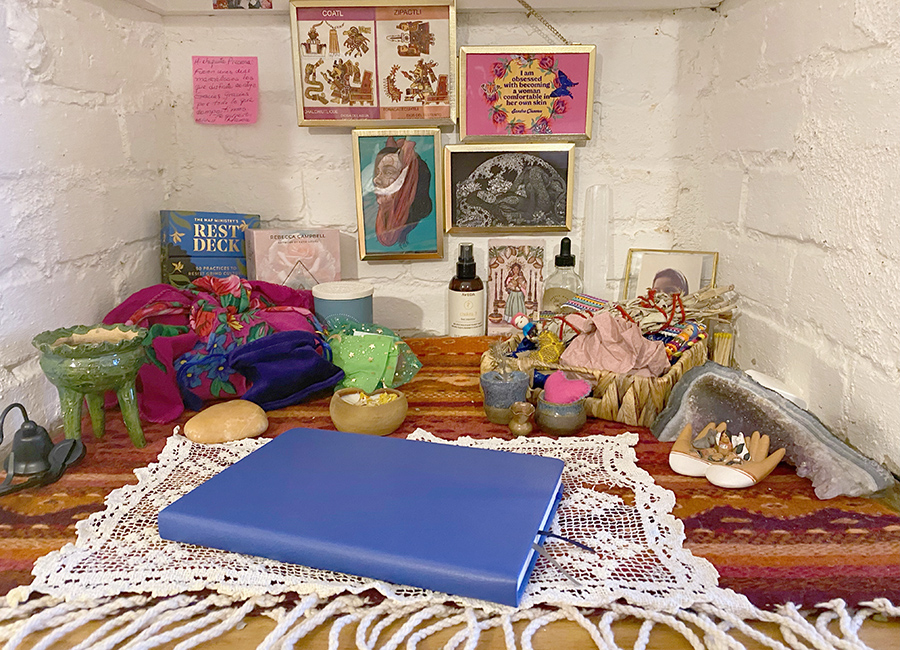

Ovalle Martínez keeps an altar on top of her bedroom dresser. It includes a small woven carpet from Oaxaca, photos of her ancestors, inspirational messages, incense, sage, and a rosary that she purchased at a church in Italy. She said she doesn’t see the practice as contradicting her Christian faith.

“When God said, ‘Take stones from the Jordan as a reminder of how I opened the waters here,’ God was saying, ‘Remember the things that I have done,’” Ovalle Martínez said. “Altars serve as those reminders.”

Lopez recalled his own experience in finding balance between faith traditions. The church he grew up in taught that celebrating Dia de los Muertos was not a Christian practice.

However, after seeing the movie “Coco,” he realized how much never experiencing that part of his culture bothered him.

“It was kind of that bridging that I was looking for, where my culture, my spirituality, my beliefs in God kind of came together and let me walk myself through that bridge to connect a part of my identity that I think I needed at that time,” he said.

He found healing through the practice of remembering his ancestors, and now he’s teaching the tradition to his daughter.

How can you contribute to passing on movement history?

“I’m being a puente with my daughter, because I’m connecting her with that piece of the culture, and I’m connecting her to my dad, to ancestors,” Lopez said. “I’m inviting her to remember and to realize that it’s important to have those connections.”

Ovalle Martínez said some puentes struggle to identify as Christians because of policies pushed by many Christians in the United States that feel harmful to puentes’ identities and their families’ well-being.

“They’re looking for a new home, and they haven’t forgotten their roots,” Ovalle Martínez said of these puentes. “They haven’t forgotten the God who has walked with them. They’re finding and searching, and they’re having different interpretations of what that looks like. Puentes is a place where they can do that safely, where they can do it not alone, where they can feel like they can do it in community.”

Though it started in Southern California, Puentes Collective is slowly growing, with retreats planned this year in Washington and Austin in addition to Los Angeles.

Lopez said people interested in supporting similar efforts where they live should look for the puentes in their own community, and he emphasized that many puentes are women even though historically women often have not been allowed to take leadership roles in many churches.

“You will find them. They’re there,” Lopez said. “Every Latino church has a puente. Every immigrant church has a puente.”

How do you create space for culture, spirituality and beliefs to come together?

Questions to consider

- What does it look like to decolonize your faith?

- Where can you come alongside the efforts of others to make a contribution rather than starting something new?

- How is your church helping bridge different generations of people in your community?

- How do you create conversations with the goal of understanding rather than change?

- How can you contribute to passing on movement history?

- How do you create space for culture, spirituality and beliefs to come together?