Tiya Miles did not set out to write a spiritual biography of Harriet Tubman.

Miles, the award-winning author of such books as “All That She Carried,” expected to write about Tubman’s environmental awareness. While Miles’ research reinforced the importance of the natural world to Tubman, it also raised up the significance of prayer and a relationship with God in Tubman’s life.

“Once I saw the centrality of faith in her life and the ways in which she was in an interior head space, a thought space, a prayerful space with that core commitment within her life, then I could see her ministering along the way,” Miles said. “I couldn’t see it before.”

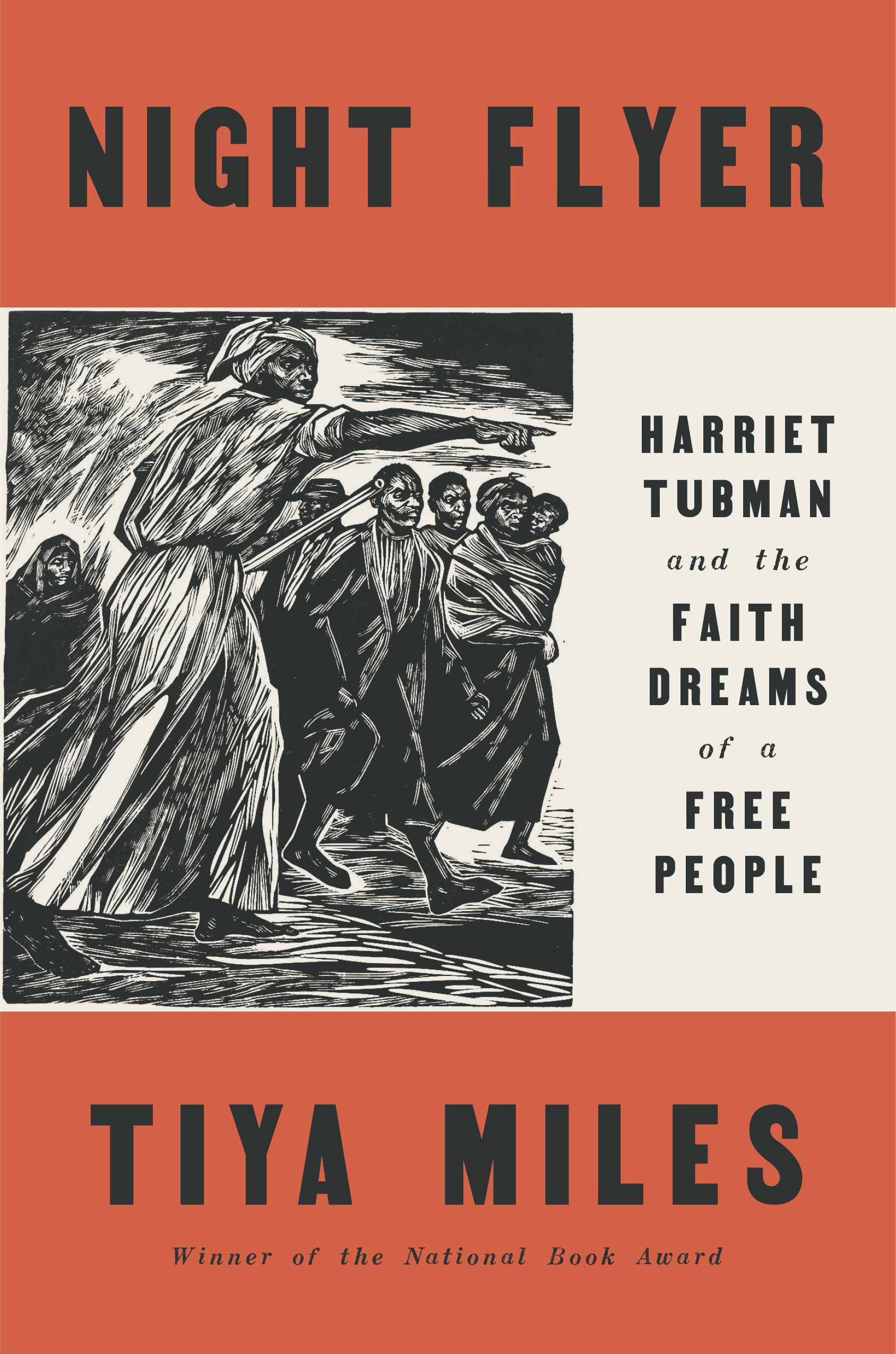

In her newest book, “Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People,” Miles chronicles Tubman’s connection both to nature and to God. The following is an edited transcript of an interview between Miles and Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne.

Faith & Leadership: Why a spiritual biography of Harriet Tubman?

Tiya Miles: One reason really is quite practical, coming out of my desire not to simply reproduce what has already been done. There are a number of strong, well-researched, incredibly detailed biographies about Harriet Tubman that already exist, and I saw no need to try to reinvent the wheel. At the same time, I know that there are figures in U.S. history who have 1,001 biographies written about them — Abraham Lincoln, all the presidents — and nobody asked, “Do we really need another biography of George Washington?”

Tubman is just as important a figure, and so I thought that it was fair, and beyond that, that it was right to take on the challenge of writing a new book about her. But that book needed to carve out some different space so that it could sit alongside existing biographies by people like Kate Larson and Catherine Clinton and complement those existing works, as opposed to competing with them.

When I entered into this project, I actually expected to be writing an environmentally themed biography of Tubman. I was very interested in enslaved people’s environmental consciousness, as I put it in some previous writing, in some short articles. I was interested in Tubman as an exemplar of Black tradition, landscape and environmental ecological awareness in action. I fully intended to write that book, to write an environmental biography. Then I got back into the primary sources about Tubman’s life, which I had read many years ago but which I hadn’t really read closely and recently.

When I turned back to those as-told-to early memoir-like biographies of Tubman dating back to the late 1800s, I was very glad to see that my environmental theme was going to hold. That seemed to be a very strong part of Harriet Tubman’s experience of her worldview, her perspective. But what really knocked me over was the way in which her spirituality, her faith, her identity as a woman who walked with God were actually paramount in the way in which she seemed to understand herself. I wasn’t expecting to write a religious history. I wasn’t expecting to wade in these particular waters, but this was where Tubman very clearly was in her life.

I would go so far as to say that if there’s one thing that we can truly know about Tubman, it is that she was a woman of deep faith. And this characteristic of her personhood, of her personality, is visible through all the different phases of her life, from some of the earliest memories about childhood that she shared with interviewers all the way to the very end of her life and to the memories of her that descendants have shared in oral history interviews with the Maryland State Parks system.

So it had to be a faith biography. I suppose it’s just kind of lucky for me as a researcher that Tubman’s Christian faith really coincided with her understanding of and sense of the natural world. I brought these two things together and ended up writing a faith biography, which is really an eco-spiritual narrative, or eco-spiritual interpretation, of Harriet Tubman’s life.

F&L: With the eco-spiritual element, you used the phrase “luminous pragmatism.” I love that.

TM: That is a notion that comes out of these two different pillars of Tubman’s life. The luminosity, the illumination, the sense of light and being able to almost rise above a set of circumstances with the help of the God of her belief, was such a key feature of Tubman’s life. It led her to be someone who would play a role in rescuing other people.

She really thought of herself as being in partnership with God in this role. She was not their savior — she would not have described herself that way — but I think she would’ve believed that God was doing the saving and she was doing the helping. There was just this light-filled, luminous, elevated quality to her experience that I wanted to capture with that phrasing.

She also had to be able to access water, to find food, to understand where the trails and the roads would lead. She had to be able to read the natural science around her. She had to be able to do the work of living practically on the ground to survive her own life and also to aid others who were seeking their freedom. It’s those two aspects of her way of living that, for me, came to really dominate the picture I had of her. It’s that twinned nature of being, which is about the looking up, the luminosity, and also the looking down, the groundedness and the practicality.

F&L: There was a sense of ministry for her.

TM: Absolutely. It took me a while to see this. I think I had made the mistake that many of us make of imagining her as somebody who was always active in the world, but really more an actor and a doer than a thinker or a philosopher. I imagined her navigating the woods and moving through the swamps and being this heroic figure in a very physical sense. She was all of that, but she also was always in her own mind and in her own spirit of communication with God.

She was a prayerful woman and a prayerful girl when she was being leased out by the enslaver of her mother and her siblings to other enslavers in the area where she lived, around Dorchester County in Maryland. Of course, she was terrified. She was lonely. She was desperately sad in this place, being away from her mother at the ages of 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and she would go off to a place alone and pray.

It took me a while — because I had this stereotype of her always in action — to realize that she was also often still, and in those still moments, she was praying. She was talking to God. She was seeking help. She was offering propositions and ideas to God. She was having a conversation. She was getting back what she believed to be direction and strength, and she acted on the messages that she received from God.

She believed that God was the answer to the problems that enslaved people face, which was their ongoing bondage and degradation, separation of their families. She believed that God would overturn the injustice of it all.

She also thought that as important as freedom was and as central an aim as that was for her, proximity to God, or closeness to God, or being able to listen to God and follow God’s direction, should also be a core feature of a person’s life. It was a core feature in her life from the very beginning that we can ascertain from her memories of childhood and to the end of her very, very long life.

She was constantly in a ministering relationship with other people that she spent time with. I think she began this process as a child of parents who were themselves devout Christians. I think she experienced them as sort of ministering to her in their teachings about being committed to a relationship with God that would help one to know rightness from wrongness. She then continued that when she was herself a young, enslaved woman dedicated to this freedom mission.

When Harriet Tubman was with a group of freedom seekers and they knew that there was danger right behind them, when she had them pause and she prayed, she was showing them how to face up to tremendous threat. She was showing them how to seek a greater or a higher strength. She was showing them where her resources came from. And her resources were their resources as well, because she was their guide through these very troubled times.

There was one story that I recount in “Night Flyer” that I had read before, but when I read it again with these new lenses, it just jumped out at me. This was a time when Harriet Tubman and the group of people she was helping to move toward freedom recognized that there were people after them who were directly on their path. They were right behind them, and she wasn’t sure what she would do. In times like this, it seems to me that the evidence shows she always prayed first. That was what she did, or another way to say it could be that she opened up the line of communication with God. She listened.

When she listened, she then seemed to have remembered almost kind of suddenly that, “Oh, there’s a place over here where we can hide.” That kind of moment, I think, shows not only how potent her interior life with God was but also that she was bringing other people into that interior life by showing them in these moments of gravest danger, “We must turn to God, and there will be protection, and there will be help.”

This, to me, is a part of Harriet Tubman’s story, a part of her perseverance that will always remain a mystery. And I decided to let it be mystery. I decided that I can’t get to the bottom of it. I can’t figure it out. Every indication that we have of the way in which Tubman carried out these Underground Railroad missions tells us that she didn’t lose people on those trails.

Every story that we have, every piece of evidence that I found, that I’ve seen that other scholars have found, indicates that when she opened that communication channel with the God of her belief and when she got information back and when she acted on it — and she always acted on it — she was successful at keeping people protected. They were delivered from those moments of great danger again and again and again.

“Night Flyer” is not a theological book. I wrote this as a scholar, and yet people can draw their own conclusions from these moments of mystery. They can draw their own conclusions from what seems to me to be Harriet Tubman’s consistent ministering to people that carried on way beyond her time on the Underground Railroad and way beyond those moments of hunters and trackers being a few steps behind in the woods.

After she obtained her own freedom and helped free dozens of other people through the Underground Railroad, she ministered to people by shaping a community in which she could care for people and they could care for her during her periods of sickness and into her elder age.

F&L: You make the point of naming other Black holy women of the same period. Could you talk about your decision to include them?

TM: I think that we carry that image of Harriet Tubman with us, and even people who knew her at the time, abolitionist allies, saw her as being not just unique but also strange. There was an exoticizing tone to the way in which they described her, but Tubman was not wholly unique.

There was a circle of women who shared her very deep religious conviction and who shared a prophetic aspect of their lived reality. There were Black women who were living in Harriet Tubman’s time who were actually her contemporaries, chronologically speaking, and also in terms of what they experienced in their lives, who did some of the things that Tubman did in their own places and in their own ways, and who said similar things to what Tubman said in terms of God speaking to them and what it is that they saw in a visionary sense, prophetic sense, in the world and around them.

I saw this very clearly after I realized that spirituality had to be at the core of my telling of Tubman’s life. I went back to some of those early [womanist theology] texts that I had read in graduate school and reread them. The narrative of Jarena Lee, the narrative of Julia Foote, the narrative of Elizabeth.

It was going back and reading those texts that led me to see the similarities. Many of these things that Harriet Tubman did that people in her time and even our time think were strange or odd or uniquely only about her, these women did too.

Harriet Tubman continues to stand out for her work as an Underground Railroad activist, for that precise work that she did going back to Maryland and personally aiding freedom seekers as they made their way north. These other women I’m talking about also did incredibly courageous things. They also pushed against everything their society said they should be doing.

In this context of extreme fear and emotional suffering and hard labor, all of these women, Tubman and Lee and Foote, Elizabeth, they found God; they turned to God. They felt they had a call from God to do a different kind of work in the world than they were presently doing, which was the work of domestic servitude, often, or the work of actually being a wife and devoting themselves to the domestic labor of their own households.

They felt God calling them to preach, and to answer that call was incredibly brave, because the people around them did not see it as appropriate for them to be doing this work.

The people around them, including Black people around them, saw this as men’s purview. This was men’s work to be preaching, to be traveling, to present yourself as somebody who was vested with the authority that God can bestow on a person just to spread God’s word, to be able to have the authority to share your spiritual visions. This was not a role that women were supposed to be performing.

They were supposed to be taking a step back, being subordinates to the men, helping in the background, etc. When these other women decided, “Oh, I’m going to answer that call,” they were challenging everybody and everything around them, much as Harriet Tubman was doing when she decided, “I refuse to remain a slave.”