I was visiting someone with whom I have a complex relationship when a wise friend texted words of advice: “Don’t look for bread at the hardware store.”

The phrase, attributed to addiction recovery programs, reshaped my attitude and expectations so that I had a much better encounter than I had imagined might be possible. Reflecting more deeply on that visit afterward, I came to the sharp realization that I have been shopping for bread at hardware stores my entire life.

Remember the often-told story about the pastor who asks the children in church, “What is grey, has a fluffy tail, climbs trees and eats nuts?” A child speaks up, “Well, I believe it’s a squirrel — but we're in church, so the answer must be Jesus!”

We are in a store, so there must be bread.

At the height of the pandemic, our pastors, who are typically trained to preach to their congregants face-to-face, had to adapt their preaching, teaching and Bible study leadership to a ring light in an empty room and a cellphone, operating with little to no technical support. They had to figure out how to keep the lights on and the tithes coming while holding funerals at a distance.

And miraculously, they learned quickly how to make bread without a recipe or baking lessons. We ate it up. And we’ve continued to ask for more.

Too soon for a “bread of life” joke?

Meanwhile, my conservative evangelical upbringing taught me that the Bible holds relevant answers to any possible challenge I might face in life. “What would Jesus do?” bracelets were taken seriously, no matter the context.

How entitled are we to believe that one person can be all things to another? Or that one book holds the answers to absolutely every question? Or that we should ever even consider looking for bread at the hardware store? Why would we look to someone or some place for things we know they cannot provide?

That’s not looking for bread at the hardware store; it’s expecting gourmet pastry! And yet we regularly have similarly unreasonable expectations of our churches and faith leaders.

With the expectation of churches to be “relevant” to what is happening in the world, we place our leaders in impossible situations. Polarizing politics, systemic injustices, financial inequalities and racial unrest push clergy into positions of community organizers and crisis negotiators that may be new to them.

Ministers are doing their best. They see the challenges, and they want to help; they feel called to help. But they can only do so much.

In the face of narratives of declining memberships, budgets in the red and loss of prominence in the public square, church leaders stretch themselves and are willing to try almost anything to reverse the trends. They’ve maintained virtual services while attending to people who have returned to the pews, even as volunteer numbers have not bounced back.

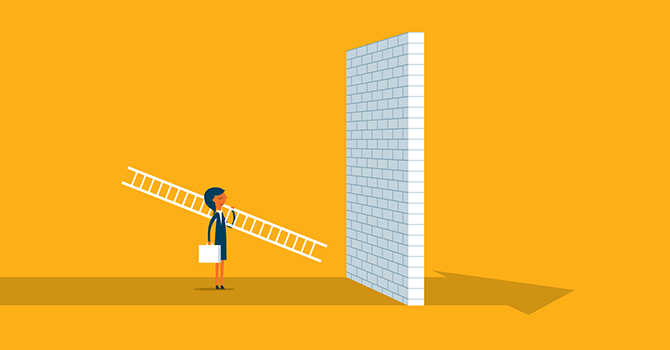

However, when we look for bread at the hardware store — when we come to people and places with specific needs they are not equipped or able to meet — everyone ends up unsatisfied. Those who hunger find themselves frustrated, because there is no bread to be found. Those who work at the hardware store are bewildered, because they clearly sell nails, saws, wood and buckets, so why would someone come to them for grocery staples?

Granted, sometimes those who hunger are so malnourished that they don’t even recognize the kind of store they have entered. They are desperate to have their basic needs met. In such moments, it is often appropriate to grab a bag of chips or a candy bar from the checkout area to address that immediate crisis and then give resources and directions to a grocery store where more substantial types of nourishment are available — at least in a neighborhood where there is a grocery store.

The quick and often impressive adaptations churches and faith leaders made during the lockdown were survival responses to a literal worldwide crisis, and we became used to them providing everything that we needed. We grew accustomed to churches being the places where we could be spiritually fed from our couches in our pajamas and get our COVID-19 vaccinations and pick up extra food because the kids weren’t in school to be fed and meet our relational needs through creative outdoor socially distant gatherings.

When the world was in crisis, the church innovated admirably in ways it hasn’t in generations, and thank God for that. Some of those innovations should become commonplace in the ways we worship and gather to be the hands and feet of Christ in the world through shared leadership within our communities.

Other practices, services and ideas the church temporarily assumed probably need to be handed over to professionals who make their living doing what faith leaders stepped up to do in an emergency. That may not be possible in communities that remain painfully underresourced beyond what faith communities have long provided, but it can be in others.

What might happen if we empowered our clergy to lead from their God-given gifts and talents rather than from our own needs and expectations? What if we shopped at a bakery for bread and visited the hardware store for nails and wood?

Ministers are doing their best. They see the challenges, and they want to help; they feel called to help. But they can only do so much.