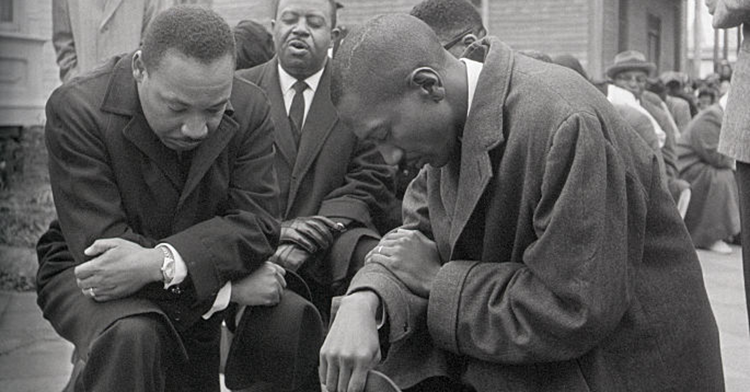

As leaders of historic congregations, we stand on the shoulders of generations of clergy and laity who navigated immense challenges. As inheritors of their legacy, we ask ourselves: What truths are we collectively avoiding? How can we use their strength to build a more honest and hopeful future and avoid moral panic?

These questions urgently push us to deeper reflection and courageous actions to ensure that our congregations become sources of hope in a world that is becoming more and more dismal.

In this season of turmoil and uncertainty, all of us are faced with a crucial choice of succumbing to despair or harnessing our inner strength to meet the challenges before us. James Baldwin pointed to this imperative in his poignant work “Stranger in the Village,” demonstrating how turning a blind eye to reality can lead to one’s own demise. Baldwin’s characters, in their reluctance to confront uncomfortable truths, invited their own destruction.

This desire to remain “innocent” and avoid the realities of our history, society and ourselves is not accidental. The illusion of innocence fuels deliberate acts that undermine both the potential for life and a commitment to interdependence.

Such willful ignorance can lead to a devastating collapse of the human contract, making the idea of a beloved community seem implausible. The decision of Baldwin’s characters to “shut our eyes” reinforces doubts and despair, making them the norm.

Complicity in social problems

Another result of willful ignorance is what we call conscious apathy — a type of disengagement from the continual struggle for liberation. We are unable to acknowledge our involvement in serious social issues because of fear and a desire to remain anonymous or safe.

When moral panic and conscious apathy marry, we seek absolution from the present conditions by marking ourselves as invisible, safe or unbothered — unable to confront truth, because to do so would require individuals and institutions to honestly acknowledge their complicity in human and social destruction. Therefore, death — of the known and unknown, and more crucially, of democracy — evades the lessons found in and through experience, history and wisdom, becoming a mere afterthought amid a diminished existence.

Institutions like the church also must navigate these complex waters, as Jamar reflects:

At the historic Chicago church where I pastor, we’re committed to serving the marginalized. Our soup kitchen and clinic embody our faith, but we grapple with societal apathy. Can we truly live out our faith without addressing systemic issues?

Thom Rainer’s book “Autopsy of a Deceased Church” prompts us to reexamine our impact. Are we offering temporary relief or actively fighting inequality? If our charity doesn’t lead to sustainable change, are we perpetuating dependency? As pastor, I feel responsible for challenging the status quo; I question whether we’re doing enough to dismantle the systems causing suffering. Our legacy depends on embracing a more transformative approach, actively creating pathways of liberation.

The Black church has also at times grappled with the internalization of societal pressures. Balancing the spiritual care of its members with the prophetic call to challenge injustice has been an ongoing tension. Acknowledging this complexity allows us to recognize that even institutions born out of struggle and the pastors at their helm can be susceptible to the subtle forces of apathy and complicity.

The illusion of American exceptionalism

The concept of American exceptionalism fosters another dangerous illusion — a belief that we are somehow superior, immune to the flaws and struggles that plague other nations. It’s a self-deception rooted in a misplaced faith in institutions, systems and structures that are inherently temporal and susceptible to corruption. This illusion obscures the grim realities of war, greed and poverty that persist within our society.

Toni Morrison’s words in The Journal of Negro Education serve as a stark reminder of the consequences of this delusion. When our lives become commodities, manipulated and controlled by market forces, we risk losing our sense of self and agency. We become passive consumers, alienated and disconnected from the urgent need for connection.

As Morrison writes in her 1995 article “Racism and Fascism,” “We will find ourselves living not in a nation but in a consortium of industries, and wholly unintelligible to ourselves except for what we see as through a screen darkly.”

This conscious apathy, this acceptance of the status quo, further entrenches the illusion of American exceptionalism. We dismiss the pressing issues that demand our attention, clinging to false narratives of inevitable progress. But complacency will not lead to liberation.

True transformation requires active engagement, as Jason notes in his reflection connecting the openness to critique that is common in academic spaces but not as much in church contexts:

In the college courses I teach, I foster an environment where students are active contributors, questioning dominant narratives and analyzing power structures. By centering student voices, I aim to dismantle illusions and work toward a more equitable future.

While the classroom challenges narratives, sometimes this isn’t the case in the church, which can mirror society’s tendency to cling to illusions. Passivity hinders the church’s mission, much as the illusion of American exceptionalism fosters complacency. Empowering congregants, then, necessitates a confrontation with ingrained practices, similar to dismantling social myths.

Whether in the contexts of the classroom, the church or any facet of our lives, we must challenge dominant narratives, question entrenched power structures and refuse to be silenced. Transformation requires a collective commitment to dismantle the systems of injustice and build a more equitable future. Only then can we break free from the illusion of exceptionalism and work toward a society that truly lives up to its highest ideas.

A call for deeper faith and courageous action

As pastors rooted in the Black church’s legacy of resistance and resilience, we are compelled to ask: Can faith be considered genuine if it does not motivate us to care for those at the margins? The Black church, as a sanctuary for social change, reminds us that true faith is inextricably linked to the pursuit of justice and the dismantling of oppressive systems.

The fragility of our democracy can understandably trigger panic. However, panic cannot create lasting change. Do we merely strive to sustain a flawed democracy, or dare we aspire to construct something far better? This ecological, human, theological and social imperative demands our conscious engagement. A crumbling democracy that results in human decay must not be met with apathy or despair. This call to action is one that interrogates the consequences of inaction and rekindles a shared hope for the next generation.

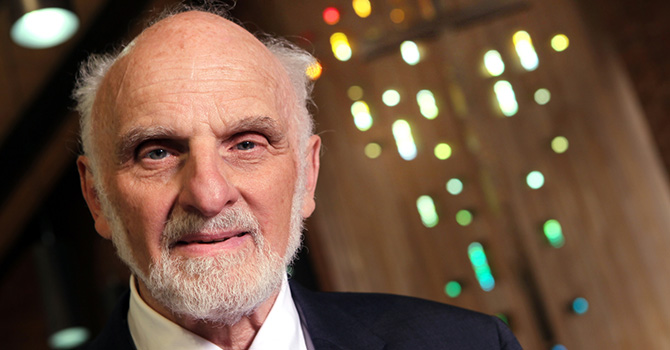

Allan Boesak’s “Dare We Speak of Hope” reminds us that hope is an active language capable of articulating our deepest yearnings for a life of abundance and fulfillment. This language, a divine gift and a human right, possesses the power to lift us from the depths of despair. It empowers us to embrace a liberating God who creates pathways where none seem to exist, guiding us toward a realm of boundless imagination, where freedom and joy prevail. This is the aspiration for any community — be it a people, a congregation or a society — when confronted with a world seemingly paralyzed by despair.

How can faith institutions and the individuals within them confront uncomfortable truths in order to break free from the cycle of apathy and destruction? We must be wary of “pseudo truth telling” that obscures the genuine self-reflection and dialogue needed to bring about meaningful change.

As pastors, we grapple with the complex realities of our world. Yet we remain steadfast in our belief that hope, courage and commitment to justice can lead us toward an equitable and compassionate future. We hold up the Black church’s legacy of transcending apathy to awaken the possibilities of truth telling and to actively participate in constructing a world that reflects the divine potential of us all. This is how we reclaim our role in erecting a new social gospel.