Brenda Salter McNeil has a way with words that moves people to action. She displays this in her fifth book, “Empowered to Repair,” where she urges her readers to approach racial reconciliation with the mindset that justice and faith are joined.

“I really wanted people to understand that this call to social justice, to engagement, is not some dichotomy from our spirituality. Every time I write a book, it’s always rooted in what God’s word says, because I’m really trying to say to Christians, to people of faith, that this is not a choice between this or that. They are married together. And if we don’t put them together, our credibility is in question,” McNeil said.

At Seattle Pacific University’s School of Theology, McNeil is an associate professor and directs the reconciliation studies program. She also works on the pastoral staff at Quest Church in Seattle.

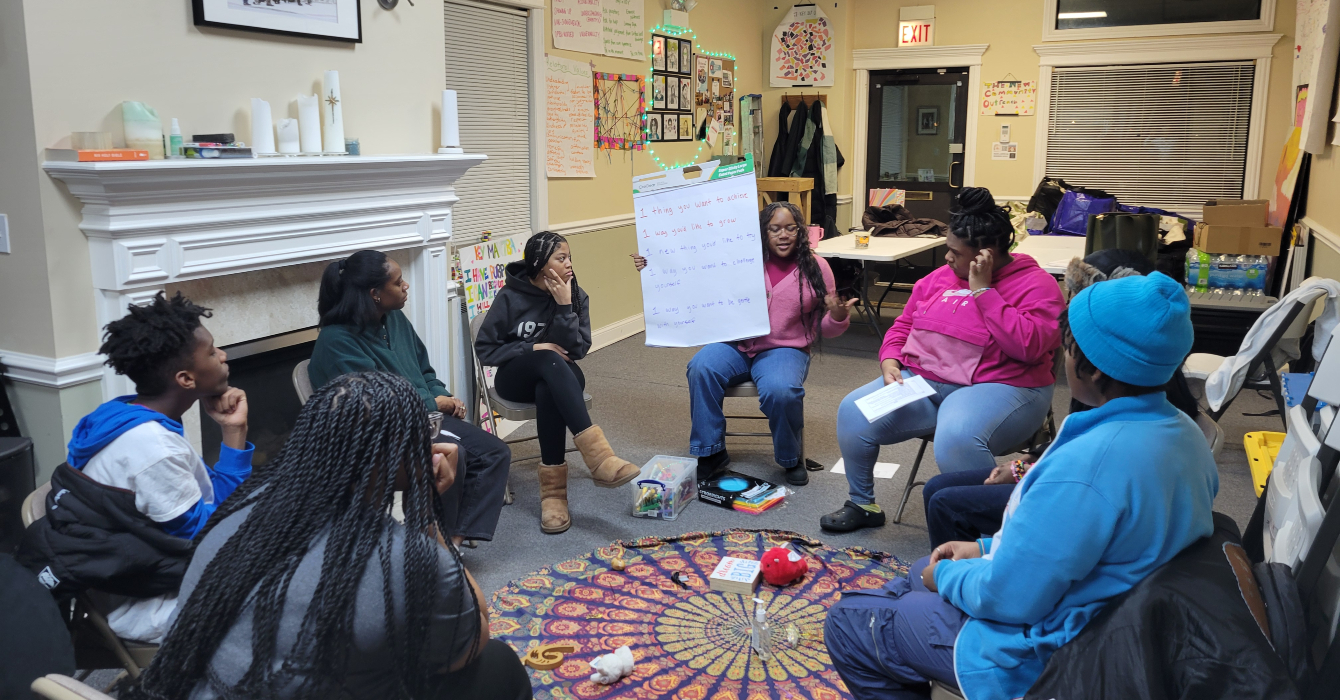

McNeil takes great pleasure in supporting and empowering young people, encouraging them to contribute to and fight for issues that matter to them.

“There’s something in that younger demographic of young adults who are wise enough, informed enough, observant enough to know something must change and courageous enough to get involved. I want them to believe that Mama Brenda, Sister Brenda, Auntie Brenda, whoever, did the best I could to give them everything I had. And I am trying to do that,” McNeil said.

She spoke earlier this summer with Faith & Leadership’s Julia Zaree French and Aleta Payne. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: In “Empowered to Repair,” you center Nehemiah. Could you talk about that choice?

Brenda Salter McNeil: I was motivated to look for a biblical narrative that dealt with the issue of repair. I wanted something, especially in this book, to address, not just the conceptual understanding of what needs to be done, but real, practical, almost step-by-step tools that a person could employ to actually fix something.

Because of the physical work required to do what was necessary, the importance of people and galvanizing them, there were things in this narrative that suggested this is a missing link in the work that we’re doing around reconciliation. I wanted to try to give it as much clarity and particularity as possible. I wanted people to not just think of it as a theory but to see it as a real, practical way to get involved.

F&L: In your introduction, you talk about growing up and not being engaged in protest; you talk about living in a faith bubble. Why was it important for you to include that part of your history in the book?

BSM: I think a lot of folks think that those who are passionate or involved in the work of racial reconciliation, social justice or whatever just happen to be like that. We can assume, “Well, those people are just good at that, and I’m not good at that.” I think that becomes a way to excuse oneself from getting involved.

We’re all human. We’re all made of flesh and blood. We all grow; we all have a journey. And so it’s not for Christians to opt themselves out because they feel like, “That’s not my personality.”

I feel like, “No, honey, you just bring your little personality right on over here, because we need all of that.” You can’t disqualify yourself because you feel like that’s just not who you are.

Your journey takes you places and your journey transforms you, and the journey is preparing you to be a person who makes a difference in some way.

Don’t put me on some pedestal as if I just woke up writing books. I didn’t. I grew up like anybody else and slowly but surely began to figure out what it meant for me to live a life of integrity.

F&L: The word “reconciliation” has baggage for some people. Could you talk about your definition of it and also how you talk about it, not as a one-time thing, but as an ongoing spiritual practice?

BSM: Some people think of reconciliation in Scripture as being reconciled to God or being friendly. It feels like a very weak kind of kumbaya gathering of people singing songs together, having a potluck. And unfortunately, we have a generation of young people who see that and they see the lack of strength, potency, agency in it, and they don’t want anything to do with it. And I don’t blame them at all.

Part of what I needed to do was to give more depth and clarity and reclaim what reconciliation means, because it never was intended to be this kind of a gathering of diverse people who sing songs together. It really was supposed to be something more.

I had to clarify even how to define reconciliation. I’d gone to a conference some time ago, and all of us were working in reconciliation in one form or other, but none of us had a clear definition of what it was. It meant different things to different people. To some people, reconciliation meant race but didn’t include gender.

For some people, reconciliation was relational. And for other people, it had something to do with justice. I had to think, “OK, what’s your reconciliation? What’s your definition?”

Prior to “Empowered to Repair” and “Becoming Brave,” I wrote a book called “Roadmap to Reconciliation.” In that, I define what it is for me: reconciliation is the ongoing spiritual practice that involves repentance, forgiveness and justice that transforms broken relationships and systems to reflect God’s original intention for all creation to flourish.

When I think of that, I think of both human flourishing and environmental flourishing. That’s the will of God. And we participate in that as the people of God, or as people who want to see reconciliation become a reality. That’s how I define it.

Until we do have a clear call to what it is we’re asking people to do, we find ourselves going in circles. And unless we clarify what is the goal, what are we leading people toward, I think we have a vision of something that we can’t attain. I am much more practical than that. My desire is to see people actually live into the reality of it. That, for me, has informed how I teach at a graduate level and an undergraduate level. It informs what I preach about and what I do at my local church. We’ve got to, as Christians, figure out how to embody reconciliation and not just conceptually believe in it.

I didn’t go looking for reconciliation; reconciliation found me. And I feel called to this now.

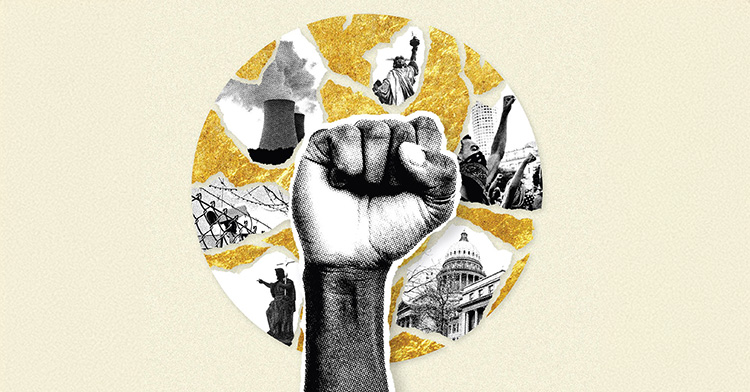

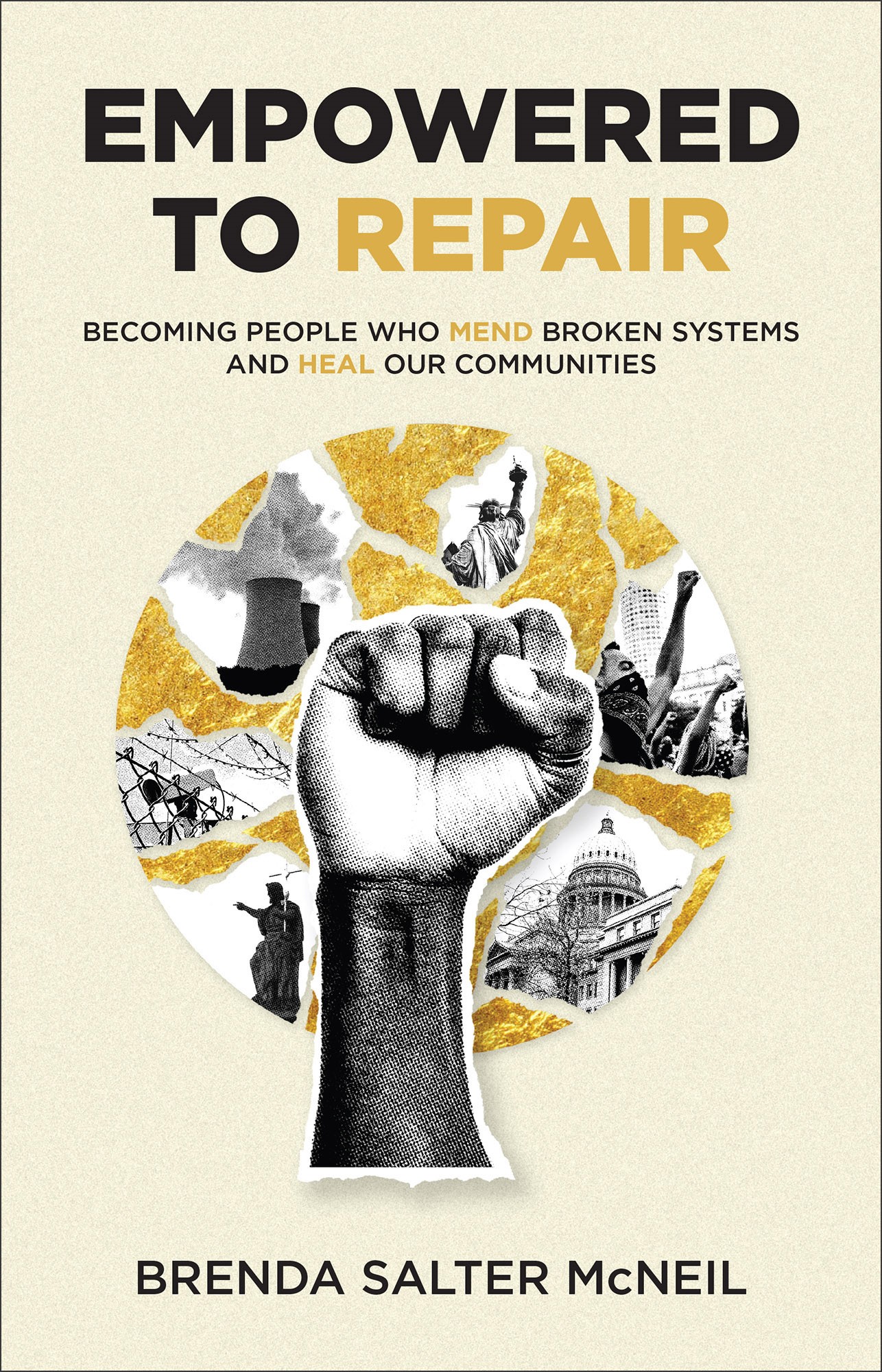

F&L: The design of your book conveys a certain message. Did you play a role in designing it, and can you talk about how it speaks to you?

BSM: I have a friend, a young man who has been in my life for some time. We worked at the same church together, and he’s a graphic designer. I love him, and I respect him. I like his aesthetic, and I like his heart for justice.

My personality is I’m friendly. My mama used to say when I was a little girl, “Girl, you’ll talk to anybody.” I hug folk and all of that. I’m just friendly.

With this book, I did not want to convey “friendly.” I think that’s what we’ve made reconciliation to be. It has been about making friends. You see diverse people on the cover. You know what I mean? Or folks holding hands. I think Christians have made reconciliation become more about just making friends. I wanted to convey that there are systems and structures that are impeding people’s lives, their ability to thrive. That does not get healed or changed, and communities don’t get fixed, by people holding hands and singing songs.

We have to address systems and structures. I wanted to show a sense of this. You need to use the power that God has given you to repair something. Things that need to be repaired have to do with our judicial system, with our immigration system. They have to do with our political system. They have to do with our environmental issues. They have to do with incarceration and who gets incarcerated. These are things that are keeping people from reaching their full God-given potential. And as Christians, we need to address those systems and structures, and that’s where reparations and reconciliation marry each other.

The fist was saying that it’s a call to using how God has given us our strength, our power, our intellectual abilities, our jobs. Whatever it is God has given us, we are to use it for the good of the communities we find ourselves in.

There’s always something that needs to be repaired. Reparations is not some radical new thing. The Bible says in Isaiah — and this really grabbed my heart, and it touched me deeply, because it’s all through here — in Isaiah 58:12, it says, “Your ancient ruins shall be rebuilt; you shall raise up the foundations of many generations; you [the people of God] shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to live in” (NRSV).

If we’re going to restore streets to live in and make it safe for kids to play, and if we’re going to deal with the things that keep people from thriving, that’s not just about singing songs or holding hands. It’s about addressing the systems that keep that from happening. That’s what I wanted this book to convey, from the very cover to the very last word I write in it.

The reason I said I’m nice is because I think people can take nice and then dumb it down to be, “Let’s just all get along.” And I feel like, “Honey, get away from me. Get away from me,” because we have been doing that too long. I’m trying to say to them, “Don’t take this sweet kindness. I’m not playing. Somebody’s got to say this.”

Most people know that I’m nice. I think this is a very strong departure from how people perceive me. I need them to know, especially as I think this might be the last book that I write.

And if it is, I want people to know we’re never going to get to where we want to go if we don’t begin to deal with systemic and structural inequalities and inequities that harm people’s lives. And that’s what people of God need to take seriously. That’s what I believe. And that’s why the cover looks like that.

F&L: You put so much faith in young people, and you even say to the church that the church needs to listen to them.

BSM: There’s something about the energy of young people, the idealism that, “This could be better. It doesn’t have to be like this.” I believe that revival comes out of that generation, out of those who are coming behind us. And I believe [we need] to empower them, to recognize the hope, the possibility that they represent, the strength that they have, the courage that they garner. I really do believe that history tells us that major movements are often galvanized with that demographic deeply involved in the work.

That’s why I’m compelled. I see them, I believe in them, and I want so much for them to feel as if we, those of us who are ahead, have done our part in paving the way for them. I get emotional, because I want to see change and I believe that they are change agents. I believe they have the desire to be change agents.

F&L: What else do you think we should know?

BSM: Sometimes I have to resurrect hope. Right now, in the political climate, [we see] the complicity of Christians — in particular, white evangelical Christians — with stuff that 10 years ago would not even have been happening. I mean, the stuff that we see happening now, where people blatantly lie over and over again. It’s obvious that it’s not true. I don’t know what’s happening around us right now.

I thank God for our faith. Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen (Hebrews 11:1). I believe that people of faith are necessary now, because if we go by what we see, I think we all just want to pull the cover over our heads in hopes that it goes away. I think we need people of faith.

That’s where hope is rooted. It’s not in what we see. It’s not in the political structures, as much as I vote and will always vote. Ultimately, I believe that the people of faith are those of us who are able to garner hope. And I think we need us now. I trust that those who are reading this will understand the important role that people of faith play in the process of healing and hope and repair.