The cry of the psalmist has become the cry of many after a year of war between Hamas and Israel. As in the psalms, so in our voices, the cry echoes from deep within our hearts and bowels. A multitude of feelings reflecting a nightmare montage of images pours out in the cry, with accents and meanings and particularity that differ among us.

Take a moment to pay attention and reflect: On what aching wound does your cry most clearly focus? “How long, O Lord?”

As our many cries make their appeals at the throne of mercy and power, I wonder: What does God hear and think and do with all of this? What, too, might we hear and think and do as faith leaders in this moment?

God, I think, hears all the cries that rise from any voice in creation. And God, I suspect, thinks about how partial is every cry that comes. God then, I’m sure, weeps and gets about renewing life with Spirit. Which suggests what we might do as well, in the vein of imitatio Dei.

“You shall not go around as a slanderer among your people, and you shall not stand idly by when the blood of your neighbor is at stake.” (Leviticus 19:16 NRSVue)

Hearing all the cries that rise demands of us humility and patience. Especially as the agonies stretch past a year, we want to know the answer, find the solution. Yet the agonies don’t only accumulate; they also multiply and divide, making things more complex rather than less so, even as the horrors compound and resolution seems more elusive.

The tension between our desire for resolution and the unfolding reality can lead us to shortcuts and oversimplifications, which by nature ignore or distort someone’s cry. We know when our own cry feels unheard or twisted to another’s concern; we need to be attentive when we might do the same with others’.

There is no calculus adequate to the integration of every claim about the past, every dynamic in the present and every fear for the future. Solving the past does not build a future; a peaceful future will be built day by day among those who have the courage to honor the truth of one another’s experiences and the compassion to protect everyone involved from harm.

Mutual recognition among those in the conflict will begin that process; we encourage it by ourselves recognizing all the many voices and experiences that we hear.

“Just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” (Matthew 25:40 NRSVCE)

Who is “the least” of the family of God? We are, of course! Social psychology teaches us that we assess our own situations differently from similar situations of others. To offer a mundane example: When I bump into someone, it’s an accident. When someone bumps into me, that person is aggressive or inconsiderate. My mistakes are situational and unavoidable; another’s are clumsy or inattentive.

In active conflict, this tendency is catalyzed by existential fear, so that the enemy’s every move is construed as threatening, prompting and legitimating defensive action. I am the victim, I am the least, and I deserve the care and attention of those with resources to offer.

A key resource available to those outside the conflict, however, is precisely their external viewpoint. Not being existentially involved or threatened allows a compassionate third party to see more clearly the dynamics within the conflict. Allyship that identifies exclusively with one party or the other and adopts that party’s experience squanders what may be even more valuable — perspective.

That limited allyship deepens the sense of dire opposition and the need for a clear victory rather than reconciliation. Thus it emboldens the allied party to press for victory while simultaneously deepening the other party’s sense of victimhood and isolation.

With perspective and wisdom, we can recognize that both parties feel themselves to be “the least” and that both therefore present us with an opportunity, not to judge which really is the least, but to respond to both as we would to Christ.

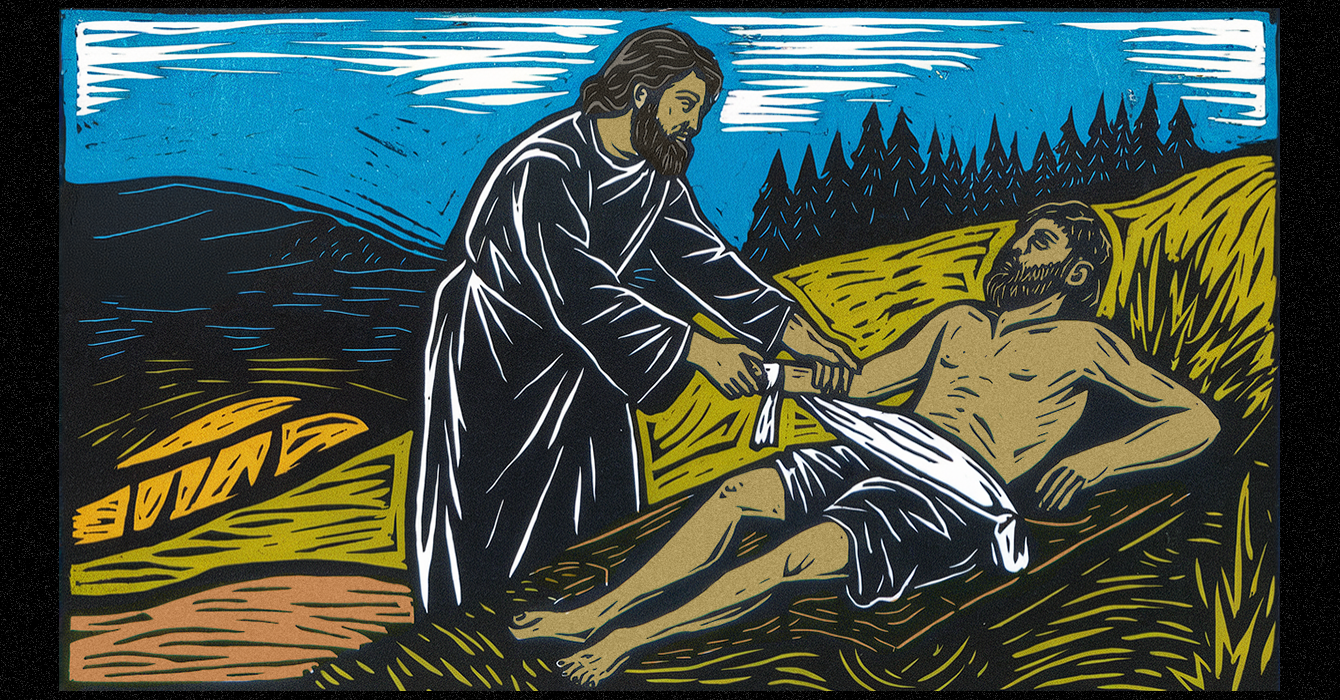

“Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor?” (Luke 10:36)

How many of us learned in seminary about the gutturally splendid Greek verb splagchnidzomai — or heard it from a pastor who could not resist sharing it in Bible study? It describes a reaction of compassion toward suffering that is as gut-wrenching as it sounds, felt literally in the guts. It is what the Samaritan on the road felt on seeing the person who had been beaten by robbers and left half dead (Luke 10:33). The Samaritan turned the feeling into action, bringing healing by every means possible.

The Samaritan does not solve the problem of highway banditry. The Samaritan sees the wounded and tends to the wounds. We who are not Israeli or Palestinian, who are not directly involved in the conflict, will not solve the conflict. That remains for Israel and the Palestinians to do.

For us, the gut-wrenching feeling best moves us toward the wounded, whoever they may be — seeking them out so they know they are seen, reassuring them of our care and support and of our hope for peace, listening to their experiences, understanding their pain, doing whatever nurtures life for them.

This can begin with our own neighbors who identify with the pain of relatives, colleagues or co-religionists in the conflict. It can extend to supporting agencies that provide front-line services in Israel, Gaza, the West Bank and the region. It can mean protest and pressure against everything that prolongs the conflict.

As our cry rises to the throne of mercy and power, we can be working to reassure and empower those who will make peace, comfort all who suffer, constrain those who would extend the violence, and mourn all that has been lost over the past year. Lord, have mercy.