As part of a comprehensive research project, clergy leaders were asked, “Are there some responsibilities or expectations in your role as a pastor that you were never trained for?” Their responses led to researchers identifying five key skill sets that clergy leaders need for their roles but did not develop during their formalized preparation for ministry.

The findings were compiled in the report “What Clergy Leaders Wish They Had Been Trained to Do and Why It Matters,” conducted by the Lewis Center for Church Leadership at Wesley Theological Seminary.

Researchers surveyed 41 clergy leaders in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area as part of the Religious Workforce Project, a multiyear initiative funded by Lilly Endowment Inc. seeking to understand how leaders of U.S. congregations are adapting in a changing religious landscape.

The survey revealed that gaps in preparing clergy for their complex roles generally include five main skill sets, according to Deborah L. Coe, the lead researcher for the project and founder of Compass Consulting and Research. The survey respondents said they were not fully equipped to handle challenges in the following areas:

- Administration and management (including finances)

- Technology

- Soft skills for leadership

- Counseling and pastoral care

- Facilities management

“In many cases, typically in mainline or Catholic churches, they find themselves as the solo pastor in a tiny church,” Coe said. “They walk in on a Sunday morning and the furnace doesn’t work. Then they’re told, ‘Well, you’re the pastor. Fix it.’ They’re just blown away, because they had no idea that that was their responsibility. Some of them told stories of having to mow the lawn or fix the plumbing.”

According to Coe, one pastor recalled how she found herself standing beside a clogged urinal shortly before attending a business meeting. In her comments to the research team, the pastor said, “I should not be standing here, staring down a urinal with a plumber, as part of my typical day.”

Another pastor expressed frustration about inadequate training in financial management. Despite the large size of the Roman Catholic congregation he leads, he said he felt a lot of pressure to do fundraising with no paid staff to support him.

“You never get trained in finance,” he said. “I never took a course on parish finance, budget, hiring, firing. You just learn as you go.”

The feelings of inadequacy among pastors were exacerbated during the pandemic when they had to move their services online to comply with social distancing guidelines, Coe said.

“They didn’t have the technological skills,” she said, noting that many scrambled to find YouTube tutorials about livestreaming or to seek help from church members. “They had no idea what they were doing.”

Some clergy leaders admitted to spending 20 hours or more to prepare one video-recorded sermon, Coe said. One of the survey respondents said he had to do numerous takes, because it was difficult to “preach to a camera.”

“They had all these existential moments they had to deal with,” Coe said.

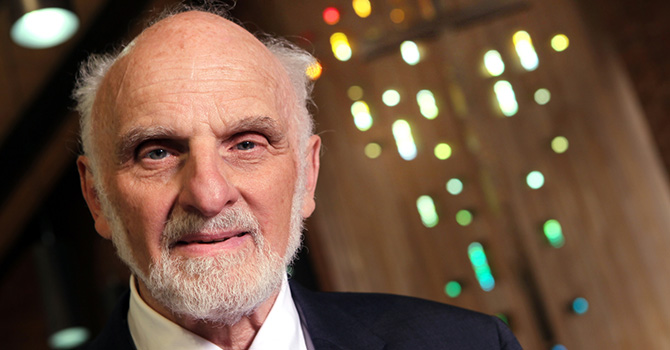

According to Lovett H. Weems Jr., senior consultant at the Lewis Center for Church Leadership and distinguished professor of church leadership emeritus at Wesley Theological Seminary, the recent survey results are consistent with those of previous research projects by The Association of Theological Schools.

“We do see some patterns that have been fairly consistent for quite a long while now,” Weems said. For example, an ATS survey asked graduates about the challenges they faced five years after graduation — areas in which their education and previous experience had not prepared them.

“Anything related to administration, managing money, leadership and dealing with conflict always seems to emerge at the top of the list,” Weems said.

Preparing clergy leaders for complex roles

With an increasing awareness about clergy leaders’ lack of training in certain areas, organizations are seeking answers, Coe said.

“A lot of seminaries are wrestling with this challenge right now. They’re not oblivious to it,” she said. “They know that many pastors are complaining. But it’s not just seminaries that do the preparation for the ministry. There needs to be better collaboration between seminaries and the churches and denominational bodies that they serve.”

In many cases, Coe said, seminary leaders assume that denominational bodies are overseeing additional development of new clergy members. However, surveys reveal that many new clergy leaders are assigned to small and, in some cases, isolated congregations where they are not receiving professional support.

Weems noted that providing additional training can be complex.

“It’s somewhat of a dilemma,” he said. “The things mentioned in these surveys tend to be things that are easily devalued or marginalized among theological school faculty and in the development of curriculum.”

Of course, seminaries must set educational priorities. “As soon as the pastor arrives, the congregation looks to them to be a spiritual leader,” Weems said. “Theological schools need to take very seriously what people have a right to expect when someone has a degree, especially a master of divinity degree,” from them.

“Schools are trying to adapt to changing times, and it is a difficult time for many theological schools,” he added. “It’s not that seminaries need to be turned into management schools, but they do need to take seriously the demands that are upon pastoral leaders and how to help them.”

Wesley has started addressing the concerns by introducing a series of courses on personal finances for religious professionals, healthy stewardship within congregations, and church finances.

Although the clergy leaders in the survey had misgivings about their lack of training, they weren’t resentful, Coe said. The survey respondents, especially those serving in Catholic congregations, perceived their roles as serving God.

“They didn’t seem to resent living very simply and having all of these burdens on them,” Coe said. “They talked about being tired and ill-prepared sometimes, but they had the attitude, ‘This comes with the job. You do what you got to do.’”