On my first Sunday preaching on death row, I had a conversation that changed my life.

After my sermon, a man convicted of murdering the mother of his baby said to me, “I have decided that I am not on ‘death row.’ I am on ‘life row,’ and I am going to live my life every day the best way I can.”

At the time, I was feeling hopeless. Professional disappointment and personal tragedies — including my father’s murder and my daughter’s death — had stifled my sense of joy. But on my first day visiting death row, the walls of my personal prison started to crumble. The man inspired me as much as I inspired him with my sermon. Perhaps, I thought, we could share joy in this desolate place.

In 2016, I was asked to preach once a month and on Christmas to the 150 or so people on death row in North Carolina’s Central Prison. I’d done prison ministry before, but as I would soon learn, I would have to imagine ministry differently than I had in the past.

The chaplain’s invitation to share faith with men sentenced to death came at a point in my life when I was ready to give up on ministry. And here, as I faced my hopelessness, I got a chance to preach. Looking back, I understand it as an invitation for me to journey forward in my own life.

Each trip to death row would give me new avenues to explore how joy can refresh and renew.

I had decided that I would preach on joy to the men on death row after learning about a preaching competition at Yale Divinity School’s Center for Faith & Culture. I honestly felt like a farce. Who was I to teach about joy to people sentenced to die? But I wanted to try it, and I prepared five sermons on joy. Over a 14-month period in 2016 and 2017, I made 33 visits to death row, preaching, teaching, worshipping and exchanging reflections on joy.

After each sermon, I asked for written responses, and I eventually collected more than 200 handwritten reflections from men and women on death row. I have included some of those in the book I wrote about the experience, “Finding Joy on Death Row: Unexpected Lessons From Lives We Discarded.”

In 2017, my sermon series “Joy on Death Row” won an award in Yale Divinity School’s preaching competition, and I was fortunate to be a featured speaker at their conference the next year.

Since then, I have been asked many questions about my work, about those on death row, about the prison setting and about changed lives. One prominent Christian interviewer caught me off guard, however, when he asked, “Do people on death row deserve joy?”

My initial thought was, “Who does deserve joy?” I wondered (silently) about the questioner, “Do you deserve joy?” Then I explained that God is the one who sanctions joy and no human has to earn it.

According to Scripture, joy is fruit of the Spirit. Does fruit deserve to be fruit? Does an apple or orange or banana deserve to be what it has been made to express? Since those on death row express that they have received joy from God, it must be divinely given. I think that God-given joy is better than any joy humans feel they can give.

On that first Sunday, my sermon quote in the response prompt was, “Christian joy is an assurance that God uses circumstances to bring believers good feelings that rest not on events but on God’s work in their lives.”

I asked those listening to take pen and paper and write down whether they agreed with my statement and why. Then I asked them to write the word “Story” and to write about an experience from their lives that would help explain their position.

The writings from death row are not always grammatically correct with perfect spelling and delightful penmanship, yet these handwritten notes draw readers into the space of the incarcerated.

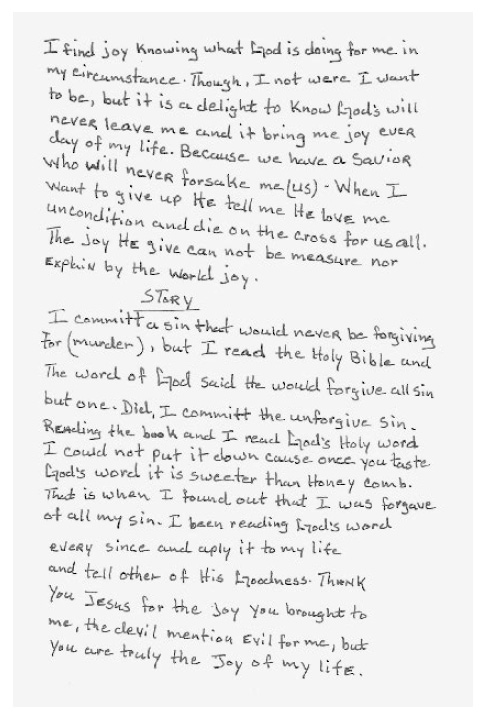

Read what one man on death row wrote:

This man often brought a wide smile to our worship services. He was a joyous worshipper and was thoughtful when he shared from his heart. He made a powerful statement about how he had changed his way of thinking as a Christian and how he had wrestled with the concept of unforgivable sin. He indicated that he was not where he wanted to be but that he still found joy. I conclude that he deserves it.

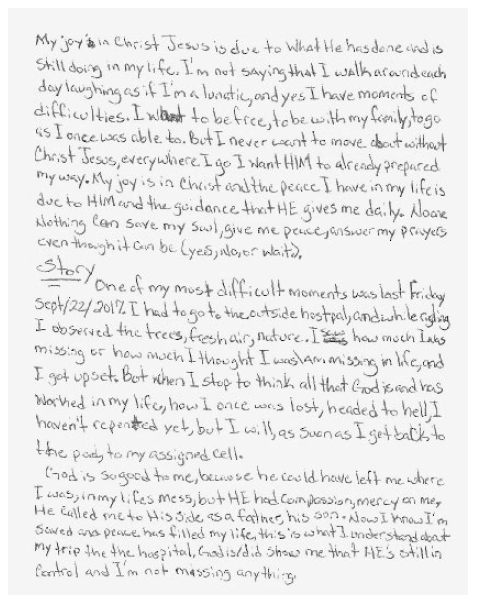

Read how another on death row responded:

This man told of his anger about missing so much when he took a trip to the hospital. His anger subsided when he reflected on how much joy God had provided to him through Jesus Christ since he had been locked up. These words caused me to pause and see my personal anger and frustration about not experiencing everything that I wanted to experience. I, like him, must reflect on the bountiful joy that God has given to me. I was humbled when I read these words. And I think this man deserves joy.

What is seen in these writings is that joy is God’s work and not our work. Our task is to say yes to the joy that God makes available to all of us.

The writings from death row are relevant to you because we all face situations where we feel locked up or locked away from what we want or from where we want to be. Yet joy is available to every one of us, regardless of how much despair we face.

I hope that those on death row, through the words of these respondents, will be humanized and remembered as children of God. And I hope that those who read their words will be encouraged. Even people imprisoned in one of the most desolate places imaginable can find joy as God pushes back against despair.