Editor’s note: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Biblical Seminary of Colombia is offering all classes online until the end of the school term in June.

For Elizabeth Sendek, leading a seminary in Medellín, Colombia, has entailed being a standard-bearer in many ways: as a woman, as a Protestant, as a peacemaker, as a scholar.

Sendek, who is the president of the Biblical Seminary of Colombia, has ambitious goals for the school, which serves the evangelical Protestant church in Colombia and Latin America and plans to offer master’s and Ph.D. programs in the next decade.

Sendek, who is the president of the Biblical Seminary of Colombia, has ambitious goals for the school, which serves the evangelical Protestant church in Colombia and Latin America and plans to offer master’s and Ph.D. programs in the next decade.

“We appreciate the opportunities people have to get their Ph.D.’s in different parts of the world, but many don’t return,” she said. “And sometimes the research they do, because of the conditions where they do their programs, doesn’t necessarily answer the questions of our context.”

The context is a challenging one. The school, called in Spanish Fundacion Universitaria Seminario Biblico de Colombia, was started in the 1940s by a missionary society. Since that time, the country has experienced a decadeslong civil war.

“My generation hasn’t known one year of peace -- one day of peace -- in Colombia,” Sendek said.

The school now offers two degree programs at the bachelor’s level, as well as continuing education and informal classes both online and in person. There are about 190 degree-seeking students and 2,500 students in non-degree programs.

Sendek and her husband, Donald, have ministered under the Latin America Mission (now United World Mission) more than 30 years, mostly in Colombia. In 1993, they joined the faculty of the Biblical Seminary of Colombia, where Elizabeth Sendek became president in 2011.

She spoke to Faith & Leadership editor Sally Hicks about peacemaking, being a woman in leadership, and why it’s important to educate indigenous scholars. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Give us some background on your institution, if you don’t mind.

Elizabeth Sendek: We are a 75-year-old institution, which is old by Colombian standards when you talk about theological education. From the early beginnings, it was a very interdenominational school.

I like to describe our school as the Baskin-Robbins of evangelicalism. In Colombia, we have the 31-plus flavors or faces of the church -- over 25 different denominations, a whole realm of independent churches, which is a phenomenon of the growing independent churches in the world. And our faculty also represent different theological traditions.

F&L: During the years that your school has been in operation, your country has been experiencing war. What are you doing in the peace efforts, and then more broadly, what do you see as the role of the church in peacemaking?

ES: The school was started in the beginnings of the civil war, the most recent civil war, that’s over six decades old.

Because we’ve had students who have been victims of the conflict themselves, or their parents or close relatives, we started reflecting on what does it mean to be a citizen from the perspective of the kingdom of God in the midst of violence.

In the ’80s, we were already doing reflection on faith and suffering, and faith and violence. We were very much involved with the work in the prisons, where we could reach out to some of the people who were suffering and [facilitate] meetings between victimizers and victims in reconciliation.

And most recently, the last five years -- well, this is the sixth year -- we have been doing more and have been focused more on the issue of internal displacement.

It is estimated that around 7 million people in Colombia live in conditions of internal displacement. We have the largest internal displaced population in the world at this moment, and displacement continues to happen.

So we have worked in the last years with six churches around the country and seven displaced communities in a project on how is it that, from a perspective of integral mission, the church can contribute to the flourishing of persons in situations of displacement.

[We are] learning a lot ourselves about resilience and the way the church has reached out to serve people in situations of displacement. Not out of sitting and reflecting, “Where is God when people are displaced?” But out of an understanding, “Oh, this is where the gospel is.”

You reach out and you serve and you welcome. People can camp out on your property and sleep on the bench inside your sanctuary and you help them become a community again, and then you help them settle.

It has been an amazing experience for us. You find communities that have suffered displacement once, twice, and they’re still resilient and still people of hope and people who have chosen forgiveness, which is the only thing that breaks the spiral of violence and counterviolence.

So it has been our privilege to work with over 20 researchers from different fields, very interdisciplinary, and an international team of researchers also.

The product of three years is teaching material, educational materials, for churches and for persons in situations of displacement dealing with issues of mental health, economic development, and how to participate, not from an electoral-process perspective mostly, but at grassroots levels.

We are encouraging churches to use their human capital -- of lawyers, psychologists, people who are in business, teachers -- to come alongside, as part of your mission, and help these communities.

Because we see our role as more helping the church in developing their own projects than starting our own projects. We focus on education.

So that is part of what we do, and it is very satisfying for us, just in the number of participants from different denominations in our peacemaking courses who are involved in the country, working in communities of reconciliation between victimizers and victims, reinsertion into society of people who have demobilized from the guerillas, and projects of restorative justice -- and as consultants in that part. So that is really exciting.

F&L: I also wanted to ask you about yourself. My understanding is you’re the second woman to serve as president of your institution. I wondered, as a woman leader in the church, do you see yourself as a role model?

ES: Yes, and I say this humbly, because I belong to the generation of women that in Colombia have had, as part of our role in the church and society at large, to open ways for other women.

And I have chosen not to resent in some situations being the token woman -- that I would accept that as part of my contribution, so other women wouldn’t be invited to speak in certain forums or whatever because they are women but because they have something to say.

The world of theological education is a very masculine world, around the world, and you don’t see many women presidents in theological schools. I really haven’t felt that I’ve been marginalized or treated without respect except for probably once or twice, but that would happen anywhere, for different reasons.

I see that it is important that what I do, I do well, with passion, with the aim of serving the mission of the school.

So it’s been challenging. It’s been exciting. I have been very fortunate in having great support from our board and our faculty and, I must say, from my husband, who has paid a very high price so I can do what I do. But he does it very gladly and really as a servant, which is amazing.

F&L: What price has he paid?

ES: Time. Though he works -- until last year, he worked full time at the school -- he became the househusband. He did groceries and cooked and did most of the laundry and really kept our house running, because I was traveling or busy or too tired on many occasions.

Time -- postponing some of his desires to travel somewhere, because I would be committed to something else, or too tired to do it.

And in that, I see him also as a role model. Because if you’re married and you’re in a position like I am, if you don’t have the support of your spouse, that’s very hard.

F&L: What is your personal background as a theologian and a leader?

ES: I am a Colombian, and I studied business administration and then switched to educational administration.

Working with university students is where I realized I needed to have a clearer understanding of theology and biblical studies to be able to respond to the questions and issues that were being raised by university students.

My husband is from the States and came originally to Colombia as an exchange student to study abroad with the University of California and fell in love with the country.

He had already gotten a master’s in theology before coming to Colombia as a missionary. We went back to the States and I got a master’s in New Testament, and at that time we were invited to join the faculty of the seminary.

So my focus has been New Testament, and in the last 10 years, it was mostly the writings of John.

And most recently, because of my role in the school and my relation with the regional accrediting agency in Latin America and other organizations, I’ve been doing more writing on leadership from a Latin American perspective.

So just last year, a book came out where I’m a co-author of one of the chapters on working with teams. I also participate in a projects of continuing education with and for faculty and deans of seminaries in Latin America, building capacity for other schools.

So that’s where my training and educational administration and what I do now in theology fit in the jigsaw puzzle.

F&L: Let me shift to a different question about the function of your institution. You have plans to expand to graduate degree offerings. Talk a little about that.

ES: Our aim is to offer a master’s so that students could enter Ph.D. programs abroad. In Spanish-speaking Latin America, I think there are two accredited master’s programs that offer degrees that are acceptable for [prospective] Ph.D.’s.

Our ambition is to have a research center of biblical studies and theology that would become a resource for Latin America and that would be the place where a Ph.D. program would be developed, around that research center.

How did we come about that? In our evolution of our context and of our strengths and weaknesses and possibilities, we realized that if theological education is to continue growing in Latin America, we need to develop more faculty for our schools.

As an institution, we have maintained a very strong position that although we need international cooperation to continue going, because theological education is not self-sustained, we would never sell out to someone else’s agenda and to the questions that were not relevant theologically and educationally to our contacts.

Not out of rebellion but out of a deep commitment to be contextual and relevant.

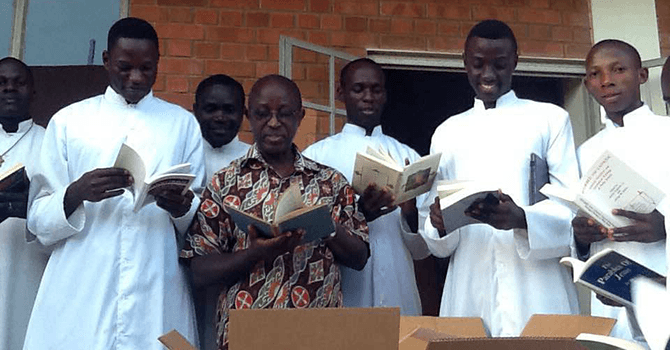

F&L: I know that you seek to form pastors in a holistic way -- intellectually, spiritually and emotionally. I wanted to ask about the intellectual training and how your seminary is equipped in terms of the library and the intellectual resources. For example, I know you’ve worked with the Theological Book Network.

ES: In the most recent years, and that’s where the Theological Book Network comes into the picture, we have worked on a program of enriching our library. So our library has really grown in quality and in numbers.

At this moment, we have the best theological library in the city of Medellín. That doesn’t mean a whole lot for a school like Duke, or for Oxford or wherever, with years and years and years of tradition and building up a library. But for us, the growth in our library has been very significant, and Theological Book Network has played a key role for us.

We have worked with faculty members to identify the areas of weakness in our library and tried to build up, because our aim is to be able to offer graduate degrees, and so we are really working on that.

One of the difficulties, though, is as you think of library resources, and that includes journals and all the bibliographical production, a whole lot more is produced in English.

So we require an English reading competency level for our students when they’re halfway through their program. They have to be able to read at a certain level, because from then on, their bibliography for their courses will include resources in English.

And there is a great cost of investing in that, but if you don’t make an effort and you don’t look out for the resources, then you say you can offer a good quality education, but really you don’t back it up.

F&L: What are the big questions for you in your context?

ES: One of the big questions has to do with ecclesiology. The Protestant church in Latin America historically defined itself in terms of reaction. Whatever the Catholics do or are, we’re not and we didn’t do.

And we continued to do that, reacting to others, but we have weak ecclesiology. So one of the questions is, Who are we, and what should we be in a pluralistic world? That’s a huge issue that shapes how we engage.

One of the other issues that I see is the great challenge of corruption and how is it that as the church we can become pockets of integrity. Because the greatest problem in our country is not violence or drugs; it’s corruption, that pervading power of corruption that has come even into the church. And we don’t see it necessarily, and that is huge.

You also have this great gap between the numbers of people who are coming to churches and the lack of trained leaders to lead those congregations. So the health of the church, medium-term and long-term, is at stake. Theological education, formal or informal -- both are very necessary for the long-term health of the church.