Elizabeth Sendek, the president of the Biblical Seminary of Colombia, is determined that her school will be able to offer Ph.D. degrees in the next decade. But in order for the seminary to educate scholars at that level, it has to have the resources to support them.

Among those resources is something many students in the United States take as a given: a library with a robust collection of scholarly books.

“There is a great cost of investing in that, but if you don’t make an effort, … you don’t back [your offer of a quality education] up,” Sendek said.

In the United States, seminary libraries contain 100,000 to 400,000 volumes. But in many countries, the typical seminary library has well under 10,000 books; the best-resourced have just 25,000 to 30,000 books.

And building an academically rigorous library collection is one of the biggest challenges for seminaries with few resources, which includes many in the Majority World, said Jeff Clark, the president and CEO of the Theological Book Network, a nonprofit that provides theological books for little or no cost to underresourced seminaries around the world.

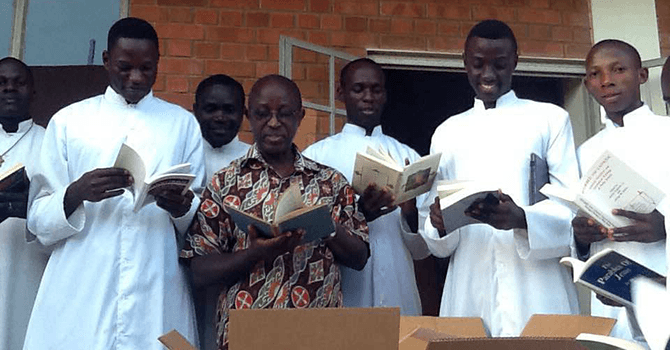

The organization, which was founded in 2004 and is based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, has given more than 2 million books so far to about 1,800 schools in 90 nations, mostly in South and Latin America, Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. This includes the Biblical Seminary of Colombia.

“Theological Book Network has played a key role for us,” Sendek said. “We have worked with faculty members to identify the areas of weakness in our library and tried to build up, because our aim is to be able to offer graduate degrees, and so we are really working on that.”

Matching resources to schools’ particular needs is an important aspect of TBN’s work; partner seminaries consult with TBN to identify categories of books they need, and TBN tries to find appropriate, high-quality books that are a good fit.

“We want to listen to our partners and hear what their needs are and do our best to meet their needs,” said Wayne Bornholdt, TBN’s director of acquisitions. “It gives us a much clearer idea of what their needs are and what strengths they want in their library.”

TBN seeks to support the Majority World church by supporting theological education, especially in countries with explosive church growth but few trained pastors.

Founder Kurt Berends (now president of Issachar Fund) recognized the need to bolster seminary libraries in his travels abroad and started the organization in his garage. Today, TBN receives donations of books from publishers, theological libraries in the U.S., professors, clergy and laypeople, which it then distributes to seminaries in the Majority World.

One of the biggest challenges is deciding which books to send -- collecting, curating and vetting the donations.

There are some basic guidelines, based on the nature and affiliation of the various schools. Catholic institutions, for example, do not typically seek evangelical resources. Methodist schools are likely to prioritize the works of John Wesley over those of Martin Luther. And the network doesn’t even bother with books about church growth in the American context; in the Majority World, growth is a nonissue.

But TBN wants to support the schools’ goals and actively seeks their input. A partner seminary fills out an online survey that offers information about the school and its needs, and TBN works with the librarians, faculty and administration.

“In the beginning, we thought we could make good decisions about what was good and fitting. But there came a point when if you are going to have a partnership, you have to pay attention to listening,” Bornholdt said.

The organization also helps support individual indigenous scholars and helps libraries access digital resources.

One goal is to help the schools build a core collection that any theological library needs. But Clark and Bornholdt say they also are aware that the books they offer tend to be from a Western perspective, and in English.

And although most of the seminaries are conservative and orthodox, Clark and Bornholdt say they aren’t trying to push a theological agenda beyond supporting rigorous theological education.

“We’re not trying to control outcomes. The church is our end goal. There are many, many roads that can take you down a path that leads to that,” Bornholdt said.