The unmistakable scent of curry permeates the spacious commercial kitchen in Richmond, Virginia’s East End, where a half-dozen teenagers in spotless white chef coats are sharpening their culinary skills while feeding their community.

The teens scrub, peel and chop several buckets of turnips and radishes donated by a nearby farm, the rhythmic ka-THONK, ka-THONK of metal knives against plastic cutting boards broken only by whispered guidance from chef Duane Brown: Slow down, slow down. Take your time. And watch your fingers. Yep, yep, perfect.

Brown, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, has been meeting weekly since November with some of these teens, teaching them first the art of “mise en place” — having all needed tools and ingredients organized and close at hand — before branching out into food prep and production. On this particular evening, Brown will show them how to braise the chopped-up root vegetables in a curry sauce before pouring them over a bed of steamed rice and dividing them into 50 separate meals for low-income seniors and families in a nearby apartment complex.

At one end of a prep table, 16-year-old Malachi Sottile scrutinizes a red onion before peeling and finely dicing it. Sottile said he’s always enjoyed cooking. He was learning some tips from his grandmother before enrolling in the culinary training class, which falls under the auspices of Church Hill Activities & Tutoring, or CHAT, a nonprofit where Brown serves as the director of workforce development. Sottile’s skill set has expanded considerably over the last seven months.

“At first, it was challenging, keeping track of all the new information,” Sottile said. “But after a while, you get the hang of it.”

Alongside their knife skills, class participants pick up life skills, learning the importance of showing up on time, asking for help, working with a team, focusing on a task and communicating clearly, Brown said. At the end of the day, participants are gaining not only the ability to earn a paycheck but also the confidence to try new things, solve problems and advocate for themselves.

In addition to offering culinary training, CHAT operates three distinct businesses that also serve as training grounds for young people in an economically depressed part of Richmond: a coffee shop and cafe, a silk-screening studio, and an urban farming outfit that includes a cutting-edge hydroponic grow operation. Those businesses employ about 20 young people, most between the ages of 16 and 22; last year, 51 young people either worked for one of CHAT’s enterprises or participated in its training programs, said Hannah Teague, the director of marketing and communications for the organization.

“Ultimately,” she said, “as an organization, we want to create more and more opportunities for students and young people to help them grow personally, spiritually, socially and academically so they’re ready for whatever’s next.”

Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

‘A rebalancing of the scales’

CHAT has what Teague calls a “scrappy origin story.” It launched in 2003 after a couple moved into the Church Hill neighborhood and turned their front porch into an informal gathering place, where neighborhood children could safely hang out and get some help with their homework. They were part of a wave of Christians, mostly white, who began moving into Church Hill from the suburbs, hoping to advance the cause of racial reconciliation and redevelopment in the state’s capital city.

That couple has since moved to South Carolina. But with guidance from the community, CHAT has expanded its scope, formalizing its after-school program, opening a fully accredited private Christian high school with priority given to low-income students from Richmond’s East End, and adding workforce training.

While there are spiritual components to CHAT's programs, students can be of any faith — or no faith, and the organization doesn't consider evangelism to be a primary focus. But, Teague said, “Christianity is in the ethos of everything we do.” In addition, she said, in a place that was once the capital of the Confederacy, CHAT’s programming is meant to prioritize the Black experience and center Black voices.

Brown said the seeds of CHAT’s workforce development piece were planted around 2005 or 2006 when the nonprofit launched Nehemiah’s Workshop, a woodworking operation where students handcrafted coasters, charcuterie boards, tables and rocking chairs. Jobs in the neighborhood were scarce, he said, and CHAT wanted to offer young people a “wholesome” activity where they could learn a lucrative trade.

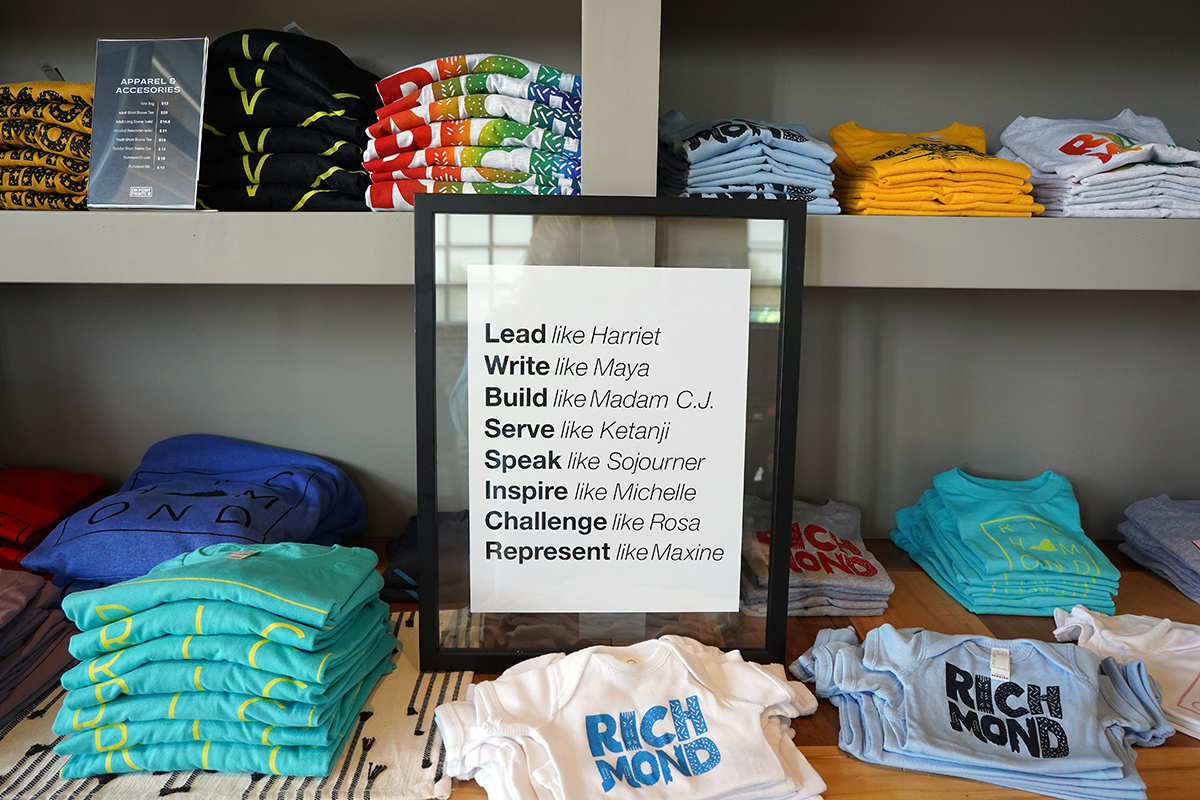

Next came lessons in sewing and silk-screening, which led to the creation of On Point Prints, a screenprinting studio that produces everything from tote bags and T-shirts to tea towels and hoodies.

In fall 2017, CHAT opened its primary food service training facility, the Front Porch Cafe, which is a breakfast and lunch spot housed in the Bon Secours Richmond Community Hospital’s Center for Healthy Living. There, about a mile north of CHAT’s main office, diners settle into comfy blue easy chairs while enjoying pastries, coffee, tea and sandwiches.

Framed photographs of neighborhood residents enjoying their front porches adorn the exposed brick walls of the interior. And some of the ingredients used in the cafe’s meals are grown at Legacy Farm, an urban gardening project, which encompasses a few parcels on CHAT’s quarter-acre property and some space in a church-owned greenhouse nearby.

Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

In addition, CHAT was invited last year to participate in a three-year pilot project, where students learn how to grow microgreens using hydroponic equipment. The equipment was purchased and installed by Dominion Energy, and maintenance and seeds are donated by Richmond-based Babylon Micro-Farms.

The entire nonprofit has an annual budget of about $3 million, most of which comes from private donations. Roughly 20% of that is set aside to support workforce development, said Jonathan Chan, CHAT’s executive director.

CHAT’s businesses are not motivated by profit as much as by a desire to equip young people with life and professional skills, so the enterprises are not expected to be self-sustaining. The goal, said Brown, is for the revenue from each business to cover about 80% of its expenses.

While not focused purely on money, the effort is still strategic. The organization paused Nehemiah’s Workshop to assess and research similar trainings and to gain a better understanding of the industry trends and student interest. The primary focus is on aligning with regional workforce goals and technology. Some of the workshop’s woodcraft items remain for sale online, as are items from On Point Prints. Shoppers can also pick up On Point’s tote bags, T-shirts and onesies inside the Front Porch Cafe.

All of the businesses have popped up at local farmers markets and neighborhood festivals to showcase their wares. The culinary trainees have hosted cooking demonstrations and tastings for family, friends and cafe customers. And, in anticipation of sourcing its lettuce from the hydroponic farm this summer, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts invited the Front Porch Cafe staff to host a pop-up event in late May, debuting its Summer Crunch salad, a mix of green leaf lettuce, quinoa, carrots, lentils, almonds and an apple cider vinaigrette that will be featured in the museum’s cafe.

Rebranding and exploring

Because the organization has evolved quite a bit over the last two decades, Teague said, CHAT is working on a rebranding effort that draws clear connections between all of CHAT’s initiatives: the social-emotional work of the after-school care program, the academic focus of the high school, and the vocational aspect of the workforce training initiatives. The organization is also exploring how best to leverage its connections to alumni so they can share their talents and life experiences with CHAT’s current participants.

Gentrification within the Church Hill neighborhood is also a challenge CHAT is trying to address, Chan said. Rising property values have meant that some of the families the organization has traditionally served have been pushed into neighboring communities, leading CHAT to expand its own service area beyond Church Hill proper into Richmond’s East End — even as far as neighboring Henrico County.

Right now, CHAT’s main office, along with On Point Prints and the Legacy garden, stands in the heart of Church Hill, within walking distance of several elementary schools and a Boys & Girls Club. But that may need to change down the road as families are displaced, Chan said.

The young people who participate in CHAT’s programs are full of promise, and their drive challenges false notions the general public may have about people who live in the East End of Richmond, Chan said.

How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

“I think we want people to have a sense of the potential, assets and gifts of our students and that we have a rebalancing of the scales to do. We want people to interrogate their own assumptions of how the world works,” he said. “If they have negative perceptions of Black and brown students, the people who live in this area, we want those to change, to be disrupted, so they can learn how they can be part of God’s work of justice.”

‘They truly want to help you grow’

In a cramped room at the rear of CHAT’s headquarters, Timond Billie, 19, is flooding a silk-screen frame with all the colors of the rainbow to create one of On Point Prints’ popular tote bags. A senior at Church Hill Academy, CHAT’s private high school, Billie said he started working at the shop in October 2021 after hearing about it from his twin sister, Jamea, who had completed a six-week summer internship there.

How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

Billie said he hopes to pursue careers in music production and real estate. The networking and marketing skills he’s picked up at On Point will help with both of those pursuits, he said. And learning about color schemes and design should come in handy when it comes to flipping houses, he said.

“I didn’t know there were so many colors — or that you could make colors out of other colors,” he said, laughing, as he pulled a squeegee through the ink, pushing the colors through the screen and onto the canvas bag beneath his tray.

Initially, Billie said, he was anxious about interacting with other people. But On Point manager Stephanie Albert was so welcoming, encouraging him to work at his own pace and to just be himself, he said, that he quickly felt comfortable. And after selling items at the neighborhood farmers markets, he doesn’t worry about chatting with strangers anymore, he said.

“I used to be really shy. But you’ve gotta break out of your shell,” Billie said. “Now, I’m confident with it.”

Like Billie, most of those who apply to CHAT’s training programs or to its job openings hear about those opportunities through word-of-mouth. Brown said he’s in regular contact with local schools, pastors and community liaisons in nearby housing complexes, letting them know when positions and new training programs open up.

In terms of tracking the progress of the program’s participants, Brown monitors whether they show up consistently and on time, how present they are when it comes to listening to instruction and completing tasks, and how well their communication skills progress, he said.

Though each workspace is a little different, Brown has accessed some youth-specific tutorials and webinars through the Federal Department of Labor’s WorkforceGPS, he said, and has gotten good advice from Catalyst Kitchens, a national network of nonprofits and regional workforce boards that operate cafes and restaurants offering job training and life skills exposure. Brown said he also makes use of industry tools, like keeping track of how many culinary trainees go on to earn their ServSafe certification through the National Restaurant Association.

The top measure of success, however, is how well CHAT instills confidence in those who participate in its workforce training initiatives, Brown said. Many of the young people who work for CHAT’s enterprises have never held a job before, he said, and many of them have little, if any, exposure to life management skills. Some face challenges with housing and transportation or are self-conscious about their struggles with math or reading comprehension. But Brown works hard to earn their trust and make CHAT a space where they feel safe enough to be honest about their needs and their goals. It’s rewarding when they share their victories with him, he said.

“There’s a point in the mentoring process where they’ve launched or moved on and you kind of stop hearing from the students,” Brown said. “And then you hear, ‘Hey, I’ve got this job interview.’ Or, ‘I got my ID.’ Or, ‘I got an apartment and a full-time job.’ And they’re demonstrating that they’ve got what they need and that they feel self-sufficient.”

Mareesha Randolph, 20, said she never really felt free to express herself or speak up about how others made her feel when she worked in retail.

“I kind of just stood in the shadows,” said Randolph, who applied for barista training at the Front Porch Cafe after a friend who was familiar with CHAT recommended it.

On her first day of work, Feb. 27, she met fellow trainee Rashá Coleman, 19, and the two have basically been finishing each other’s sentences since then. Both women said they were encouraged to ask questions and try new things, something they hadn’t experienced at their previous jobs.

What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?

“With other jobs, they just throw you right in. And back in my old job, they used to stand over you,” Randolph said. “Here, if you need help, they’re here for you, but they’re not all in your face. Over here, it’s OK to make a mistake.”

She said she still gets nervous every time she hands a customer a cup of coffee, worrying about whether she nailed the order or not. But it’s gratifying when the person takes a sip and smiles or gives her a nod of appreciation, she said.

“You shouldn’t let fear stop you from doing things you could be great at,” Randolph said. “It’s OK to try new things. That’s how you figure out what you like and what you don’t like.”

Randolph said she’s been surprised by how much she’s learned, everything from how to steam milk “so it’s not screaming at you” to how to create latte art — she’s recently mastered making a heart pattern.

She hopes to use the practical skills to get a job at a coffee shop in New York when she moves there in the fall for acting school. But the other experience she’s gained — speaking with members of the public at pop-up events, working during the high-pressure lunch rush, learning how to read customers’ body language and respond with empathy — will be invaluable in any work environment, she said.

“They’re just so friendly, and you can feel that they truly want to help you grow. They gently push you into the areas you need,” Randolph said. “And the way they do it, you didn’t realize you really needed those skills until you have them.”

Questions to consider

- Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

- Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

- How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

- How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

- What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?