Scene 19

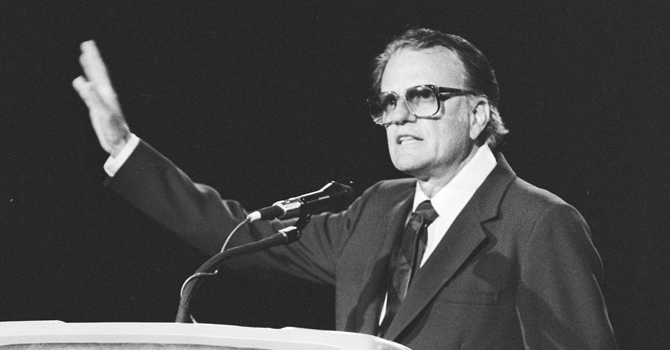

How Graham preached was just as important as what he preached. His authority lay in his words, but his words were inseparable from how he presented them.

The how started with his own preparation. We have seen that sustained Bible study and prayer were woven into his daily life routine. Those habits intensified as he geared up for crusades and during the meetings themselves. In the hours before he preached, he ran over his notes, which his secretary had typed up in sketchy outline form. Here and there he inserted cryptic handwritten comments about current events or illustrative stories or scriptural passages to weave in.

In the hotel room, Graham locked the door, pulled the shades, took a nap (with a baseball cap on to keep his long, wavy hair from crinkling up). He ate lightly if at all, reserving dinner for after the meeting. And fretted.

In the hotel room, Graham locked the door, pulled the shades, took a nap (with a baseball cap on to keep his long, wavy hair from crinkling up). He ate lightly if at all, reserving dinner for after the meeting. And fretted.

Though Graham spoke in public thousands of times, he never took his performance for granted. Before the opening night at Harringay, he remembered, he was so frightened of failure he almost turned back. At the end of a sermon, sometimes he was so exhausted associates had to help him, soaked with sweat, off the platform and directly into a waiting car.

No wonder. Tom Allen, an organizer of Graham’s 1955 Scotland crusade, said that before Graham preached he saw in him “an inner and very finely controlled tension.” But once the meeting started, “All the strain is gone, and from then on the man has forgotten himself.”

If in Los Angeles in 1949 he had preached “fast and loud,” by the time he got to New York in 1957 he had learned to dial down the speed and let the microphone do the heavy lifting. Yet his ability to hold listeners’ attention remained, or even grew. Whatever he lost by reducing the pace and dropping decibels, he gained by intensifying the forcefulness of the words.

Reporters commented on three more aspects of Graham’s preaching: his accent, his voice, and his energy. Earlier we saw that his particular accent -- “Carolina stage English” -- was just different enough to sound intriguing. It also told listeners where he came from. In the years when Graham was soaring into public prominence, the South had expanded culturally everywhere. Jim Crow was beginning to crack, and the Christian Right had not yet emerged as a polarizing stereotype of Southern religion. Southerners like the semimythical Colonel Sanders and avuncular Andy Griffith offered a vision of genteel civility.

This vision overlooked a great deal, of course, including racism, heat, and poverty, but it still rang true enough to seem attractive. Graham reminded folks of Mayberry, a receding world of small towns, summer nights, and stable values.

The preacher’s voice, a timbered baritone, sounded remarkably like that of a professional newscaster. It proved crisp enough to capture attention yet mellow enough to feel inviting. Reporters compared it with that of the nation’s most famous newscaster, Walter Cronkite. One journalist aptly called it “an instrument of vast range and power.” Graham perhaps sensed that his voice was the most recognizable part of his calling card. He took care to protect it before he preached, and between meetings he practiced how he would use it.

Energy was part of Graham’s calling card too. He never fell into the platform acrobatics of Billy Sunday, his high-profile predecessor on the revival circuit, but no one fell asleep during his sermons either. As noted, in the early days Graham prowled the platform, with Barrows furling and unfurling the microphone cord behind him. Graham rapidly bounced from standing ramrod straight behind the pulpit to crouching beside it. His right hand shot forward, fingers cocked like a man holding a pistol, while his left hand thrust aloft a large black leather Bible. In time these pyrotechnics mellowed to a more dignified style, forceful yet measured.

Graham spoke plainly and directly. Convinced that the average person had a working vocabulary of six hundred words, he made a point to stick with common words and short sentences. Though he never put it exactly this way, he instinctively grasped the import of Sister Aimee Semple McPherson’s recipe for rabbit stew: first “you have to catch the rabbit.”

If plain words formed half of Graham’s repertoire, direct ones formed the other half. In his early work with Youth for Christ, he later remembered, he used “every modern means to catch the ear of the unconverted and then we punched them straight between the eyes with the gospel.” To the end of his preaching career, qualifications such as “I think” or “on the whole” or “in general” rarely softened the rhetoric, and abstractions rarely inflated it. Illustrations drawn from ordinary life turned up constantly. Graham knew the perils of ambiguity.

Everything Graham said and did behind the pulpit pointed toward one goal: the invitation at the end of the sermon to stand up, walk to the front, and decide to follow Christ. “No matter how large the crowd,” said journalist Laurie Goodstein, he knew that “he had to move each man and woman there personally.”

Night after night the words took a familiar pattern. “Are you prepared to meet God? Does he have first place in your life? Is he the Lord of your life?” Graham assured people he would stay as long as it took. “The buses will wait.” “Come. You come. We will wait.” And wait he did.

In Graham’s mind, potential inquirers had to turn inclination into concrete action. Quietly accepting Christ in one’s heart was not good enough. It was too easy to back out when the euphoria melted into the ups and downs of everyday life.

The preacher understood the importance of perfectly spaced pauses of precise duration. He also understood the power of stillness in the audience. Standing ramrod straight, right fist tucked under his chin, right elbow cupped in his left hand, he called for absolute silence. Even in a stadium packed with a hundred thousand people, he insisted that the slightest noise or movement might thwart the Holy Spirit’s work.

A big part of Graham’s reputation -- and legacy -- rested on the response to the invitation. Admittedly, sometimes -- especially early on -- few people came forward. Occasionally no one did. But usually the response proved encouraging. Even Chuck Templeton, Graham’s early rival for superstardom in the pulpit, knew when he was beaten. “We would travel together and preach on consecutive nights,” Templeton remembered. “He would get 41 (people to answer the altar call); I would get 32.”

At the height of Graham’s career, people streamed forward by the hundreds and sometimes by the thousands. If Billy just stood there and read a telephone directory, one associate said, people still would come. When Graham died, megachurch pastor Rick Warren captured Graham’s pulpit art in five words: he knew “how to draw the net.”

But there was more. Critics charged that the seemingly endless streams of inquirers showed that the masses succumbed to the power of suggestion at best, that they were gullible at worst. Yet critics -- and admirers too for that matter -- often missed the subtleties. Anthropologist Susan Harding discerned the inner texture of the process. “At first,” she said, “you don’t get it. He seems so ordinary and accessible. He doesn’t make you think instantly that he is going to change your life. You are taken in gradually. You get captured. … [He] made Christianity come true.”

Graham knew perfectly well that inquirers came for a variety of reasons, some superficial, some profound, and some undoubtedly both at once. But the main point held. Publicly declaring a new direction for one’s life implicitly acknowledged that things had gone astray and it was time to set them right.

Visiting journalists repeatedly said that inquirers showed little overt emotion. Photographs show that some descended the steep concrete steps in the great stadiums of the world with moist eyes. Yet the emotion likely came from the hymns, not his preaching. Graham never suggested that emotion was bad, just secondary to the business at hand.

The preacher’s own tearless conversion experience, back when he was fifteen, set the precedent. And so did his deportment in the pulpit. Unlike many evangelical revivalists, he never cried. In the 1980s audiences started applauding when inquirers stood to walk forward. Graham did not like it (just as Shea did not like applause when he sang), but eventually he accepted it as a sign of the times that he could do little to change.

Also, too many inquirers -- likely a majority -- were already church members who had grown lax in their faith or former church members who had dropped out altogether. For some the decision represented a radical transformation from nonbelief to belief. One writer called transformations of that sort “sky-blue” conversions, as though they had tumbled from realms above as a sacred meteor. BGEA publicists sometimes implied that the sky-blue conversions were the only ones that really counted. Not Graham. In God’s eyes, he affirmed, new birth and renewed birth were the same.

How many inquirers stayed with their decision for five or more years? Though the evidence is both sketchy and inconsistent, it seems safe to say that for a majority the decision marked a permanent turning point in their lives.

For a sizable minority, however, it did not. Few took to the streets to renounce their decisions. They simply drifted away. Graham often compared this pattern to Jesus’s parable of the seed and the sower. Not every seed that was sowed sprouted or grew to maturity. Even so, for many the long walk to the front surely lingered in memory.

In sum, Graham possessed the gift. With a dash of dramatic flourish, we might call it “The Gift.” Newsweek’s veteran religion writer Kenneth Woodward captured it precisely: Graham, he said, could make “the simplest sentence sound like Sacred Scripture.” He combined accent, voice, animation, vocabulary, humor, timing, and, above all, authority, in a manner that proved inimitable.

The evangelist knew that the point was not to impress but to connect. Reading Graham’s sermons could be a test of endurance. But hearing them, preached live in front of one hundred thousand people, was entirely different. The message pulsed with energy as flesh became words. If numbers can be taken as an index of accomplishment, he was easily the best in the world at what he did. Maybe the best ever.

From the book "One Soul at a Time: The Story of Billy Graham" (Eerdmans, 2019), by Grant Wacker. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.