Among the self-descriptors on J. Dana Trent’s website, the most unexpected would be “preschool drug dealer.”

At its best, Trent’s upbringing was unorthodox. At its worst, it was deeply traumatic. Her parents both lived with intractable mental illness, and from her earliest years, she was often their caretaker while the family navigated criminal activity, economic precarity and homelessness. Her father took her with him on drug runs.

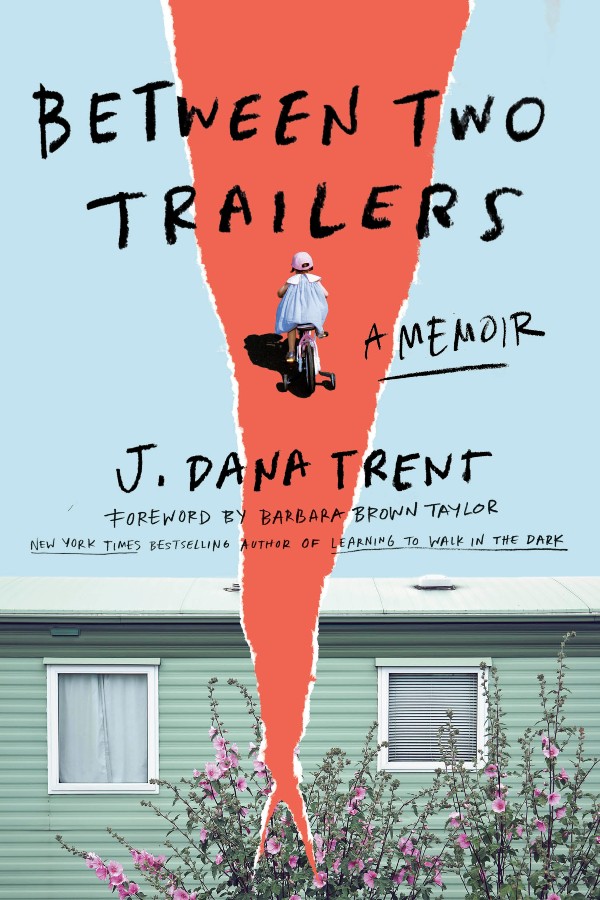

Now in her 40s, Trent is an accomplished educator and author whose knowledge of adverse childhood experiences and the benefits of therapy are neither purely theoretical nor academic. She’s lived them. Her new book is a memoir, “Between Two Trailers,” that draws on her experiences with her parents, with the people who saved her and with finding a way home.

She writes, “I’d emerged from this battlefield — its dirt and people and weapons and stories and wounds and rage — not unscathed but stronger. Courageous. Tenacious. Unbroken. Amid the casings of these blown-up lives, mine included, I uncovered healing and home in the very place where ‘you can get away with murder.’ It turns out this place — Vermillion County, western Indiana — was my home all along.”

Trent spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne ahead of the book’s release. She emphasized both the brain’s and the body’s resilience, as well as the importance of accessing professional therapy, setting boundaries when needed and lowering hurdles that block return.

The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Why was it important to you to write this book now?

J. Dana Trent: This book is literally for anyone who thinks they can’t go home. And I was one of those people. I imagine there are kiddos like me and adult children like me who also long for home, whatever that means to them, but aren’t really sure how to go about finding it.

It’s the idea that when we hit that crest of middle age — I’ll speak for myself; I’m 42, will be 43 here very soon — we start to think about life before 43 and life after 43. For me, it was very much a push-pull of longing for my roots and where I came from. Also, knowing that the way I perceive that home has shaped me and that it will continue to shape me in perpetuity. That longing for home is what pulled and pushed me forward.

I also have to write to think and to figure things out. I think it was Joan Didion who first said that. We write to figure things out. I needed to write it in order to figure out what home meant for me.

F&L: You had a harrowing childhood, on into adulthood, but even in some of those really hard moments, there were people who were trying to protect you.

JDT: The book is dedicated to them, because they are my home. They are where I find a home now. When you are a child, you don’t have a sense of who your angels are. You don’t have a clear sense of who the players are. But I always had the sense that they were proper adults. That’s the only way I know to describe it.

It seemed like my brother and my aunt and uncle and even my cousins who were my age had their wits about them. When you walked into a room with any of them, you felt like someone in the room was responsible, my grandparents included.

That was such a source of stability, because when I walked into a room with my mother or father, I felt like I was the responsible one, even as a child. I immediately began to assess their needs and sort of cup my hands open like a human Tupperware container in order to allow my mother and father to pour into that Tupperware container. Whatever they needed in that moment, I would hold it with them and for them.

When I entered into a room with my grandparents, my brother, my aunt, my uncle, my cousins, I could just let that go and I could be and be present. In some instances, a lot of instances, I could be cared for. That was such a shift. I knew it as a child, and I was grateful for it. Now I’m exponentially grateful for it, because I would not have made it through. The dedication in the book says, “I would not have survived without you.” That is 100% true.

F&L: Going into the book, what would you want people to know about your parents?

JDT: They were wild characters who still echo in my brain. Every day, I encounter some piece of life advice that they would tell me, whether it’s, “Don’t count your cash while someone is watching you,” as my father would’ve said.

Or my mother would’ve said, “Every morning, make sure you get up and act like you’re somebody.” Even though she didn’t, she always wanted me to move around the world as if I had it together, because she knew that would instill confidence.

Whether it was the street smarts of my father or the sort of proper Southern debutante-ness of my mother, between the two of them, they had all the bases of these two cultures covered — gritty Midwestern culture and polite Southern culture.

My parents were also very, very sick. We just finished recording the audiobook for “Between Two Trailers,” and the audio engineer and marketer were asking me what it felt like to get to those really hard spaces in the audiobook where I’m a child and I’m alone with my father and he has a severe, severe psychotic episode.

He’s beyond sick, and he’s suicidal, and it’s just the two of us. I’ve got to hold his suicidal ideation, which is no longer an ideation — it’s a spoken, “I am going to commit suicide.” I cried and cried during the audiobook.

Even then when we were recording, and even today when I’m thinking about it, I have more empathy than I ever have for both of my parents, because both of them had unquiet minds. I can’t imagine what it must have been like for each of them — my father being schizophrenic and my mother having all these personality disorders — what it must have been like in their brains to live in that swirl of emotion and distorted reality.

I’m grateful that I could be a witness to their illnesses and help hold that in the moment, even though I was a very small child. I would say to the reader, “You’re going to meet two characters who echo and who had a lot of challenges. But their advice, their personalities are going to shine through the book, and you will find them lovable anyway, and as you should.”

All of us, most of the time, are doing the best we can, even though we’re coping with some really excruciating circumstances.

F&L: You sort of stumbled into divinity school. Yours was not perhaps that call we think everyone will experience.

JDT: Very much so. My parents were always motivated by religion. The drug business itself became its own sort of religion within our household, with rules and rituals and litanies and liturgies. Religion was always a factor, certainly evangelical Christianity.

My parents cared about one thing, and that was whose daughter I would turn out to be. Would I be my father’s drug-trafficking daughter or my mother’s polite Southern debutante?

My mother won out in the end, because we moved to North Carolina. She wanted me to inherit the Southern charm and be her “Reverend.” That was really her motivation. She wanted a minister. She used to call me her chaplain and “Revy,” even before I was ordained.

My divinity school education, which was encouraged by my mother, really enabled me to care for both of them, because I learned lots of tools like chaplaincy and emotional support and active listening in addition to theological education.

While divinity school was not my first choice by any means, I realize now that it gave me the helping skills that I needed to care for both of them at the end of their lives, and to care for my community and my partner and my friends and church folk.

[Without those skills] I would not be able to teach world religions and critical thinking. My divinity school degree allows me to now care for community college students, many of whom are experiencing adverse childhood experiences and who aren’t sure how to navigate it.

When I walk into my world religions classroom, I obviously put on my professor hat, and I have them meet their student learning outcomes. But more than that, I consider myself a cheerleader, an encourager, someone who holds space, someone who knows how to create community and a sense of belonging, because that is exactly what Duke Divinity School taught me how to do.

F&L: When I look at the totality of your book, there are some beautiful moments in it, and there are some really, really hard moments in it. Where do you see God in this?

JDT: My view of God has always been Protector, always and forever. When I think of God, I think of capital-p Protector. I see God as that hovering, transcendental, immanent, personal Triune being who was always my Protector in the darkest days — from eating ketchup sandwiches because we only had a loaf of bread and a bottle of ketchup in our refrigerator, to doing drug drops, to my parents’ suicidal threats, to going bankrupt, experiencing homelessness, acting out in school, coping with my own trauma as it relates to my own addictions and my own body dysmorphia. God has always been Protector for me.

As a minister, I relate to that language, and it helps me extend those aspects of God to those who feel that they don’t have a protector and that they are incredibly vulnerable and left behind and forgotten. My call to ministry feels like part of my journey is not only to listen and to hold that pain, for sure — that absolute pain — and feel empathy with them, sit in the hole with them, but also to remind them that God is indeed a protector. God is many things, but God is first and foremost, for me, Protector.

F&L: What more should people know from your book?

JDT: We’re heading into a fraught time, what will be another fraught time in American culture and history. We are divided within our churches, within our communities, within our families. I think it’s hard to find reconciliation on all fronts, especially if you’re coping with past trauma.

I want folks to remember that finding reconciliation with your upbringing or finding reconciliation with folks who think differently from how you do isn’t an easy process, but it isn’t impossible. For those who want it, whether it’s reconciliation or healing or going home, there is always a path, always.

Sometimes, it means finding home in new people and places and experiences. Sometimes, it means finding home and reconciliation in reshaping those painful memories into new, positive experiences that then you have the privilege and the honor to share with others so that they can see themselves in the story as well.

Even though the stories are very different — and I had a unique experience — I’m hopeful that readers will be able to find themselves somewhere in this story. If nothing else, to be entertained, informed, and to maybe ask a few reflective, introspective questions of their own journeys. That’s my hope.