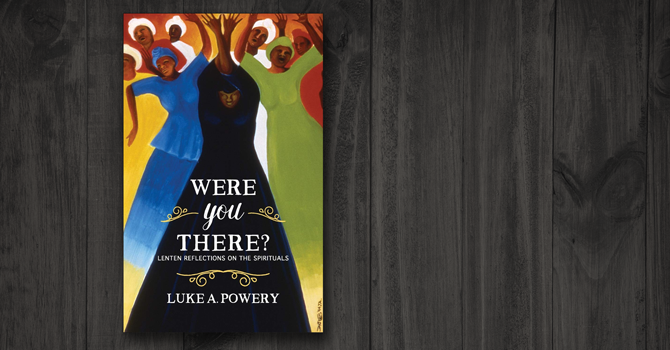

Editor's note: Read a free excerpt of “Were You There? Lenten Reflections on the Spirituals.”

Adapting African-American spirituals to the liturgical calendar is an act of reconciliation for the Rev. Dr. Luke A. Powery -- “a way to bridge worlds that don’t normally meet.”

Though the spirituals emerged from the worship of enslaved Americans and were not originally created for the liturgical calendar, their focus on the suffering Jesus makes them a good match for the Lenten season, Powery said.

“They’re earthy. They are simple yet deep. They’re not simplistic. If we allow them to work their way into our lives, I think they actually will become a part of our lives and our journeys,” said Powery, who also has written an Advent book of meditations drawn from the spirituals, “Rise Up, Shepherd! Advent Reflections on the Spirituals.”

In addition to his role as dean of Duke University Chapel, Powery is an associate professor of homiletics at Duke Divinity School. Before coming to Duke, he served as the Perry and Georgia Engle Assistant Professor of Homiletics at Princeton Theological Seminary.

He has a degree in music from Stanford University, an M.Div. from Princeton Theological Seminary and a Th.D. from Emmanuel College, University of Toronto. His teaching and research interests lie particularly in expressions of the African diaspora.

Powery spoke to Faith & Leadership about his book, “Were You There? Lenten Reflections on the Spirituals,” and why he hopes to share the spirituals with a wider audience. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: Why choose spirituals as the basis for a Lenten devotional book?

The backdrop to all of this is my work on the spirituals and preaching -- my research and book -- which was called “Dem Dry Bones.” And even predating that, my own journey and music background, singing in the church all kinds of different sacred music genres.

How do I bring this body of material, this genre of music -- what I call musical sermons -- how do I foreground them for a wider readership?

It was bringing the spirituals into conversation with the liturgical calendar. It was a way to bridge worlds that don’t normally meet, where you bring the enslaved tradition, wisdom tradition, the understanding of God, the Bible -- all of that life -- together with this generally high-church following of the liturgical calendar. Underneath this is a reconciliation of sorts.

The spirituals have been called the “Third Testament.” It is a way to say, “What can we learn from people who we don’t even know, don’t even know their names, out of the context of slavery?”

They must have something to teach us about suffering before God and the life of faith.

Someone sent me an email last night -- Day 1 in the book is Ash Wednesday, but they said, “Actually, that’s not Day 1. Day 1 is what you have at the beginning to dedicate the book.”

There are four women [in the dedication]. One is my mother, who is still alive, and three of her sisters, my aunts.

I write, “These are the St. Elizabeth sister-saints who laughed, even in their suffering.” I think about the juxtaposition, or the relationship, between laughing and suffering in this journey in Lent, and in the end, traveling to the cross. And obviously, we come out of Lent into Easter.

There is a saying, “You laugh to keep from crying.” That’s the blues. But in the end also, God has the last laugh, even in the face of death.

[Those] three of my aunts have died, and my mother is, out of 18 children, the only girl who is left. She was the youngest girl and really lived a spiritual life embodied by the spirituals.

Not enslavement, but suffering in various ways. But [the sisters] had such laughter and joy and humor on the journey, which to me was the gift of God. Even when Lent was life -- not a liturgical season -- they could laugh.

And so I remember them and I honor my mom with this little book. It’s remembering the ancestors who have paved the way for so many of us. It’s a book of memory. It’s a call to remember.

Q: What was the role of the spiritual historically? How do you see the present role of that form of music and worship?

The spirituals really came out of the context of worship, and primarily in settings in the context of slavery, in what might be “brush harbors,” or the “invisible institution,” which was where the enslaved would gather to worship God together.

In those settings, it was testimony, it was preaching, it was the songs that emerged out of a very improvisational worship experience. These songs are songs of the Spirit.

The enslaved would call them spirituals. We might put the adjective on there -- African-American, black, Negro spirituals -- but they called them spirituals because they were seen as revelations of the Spirit in their midst.

So we have expressions of the Spirit among the people that were dehumanized, and so in many ways, these are songs of life and hope, joy.

Of course, they detail suffering as well, but they are the Spirit singing through these people that were not even seen as human. It’s almost a reclamation of the Spirit, reclaiming God’s children as human beings through these songs.

We hear in the early church, “He who sings prays twice.” We hear the African proverb “The gods will not defend without a song.” Singing was a matter of life and death. As long as you had a song, you were alive.

These songs are portable, transferrable, cross-cultural, cross-geographical, because they are songs of the Spirit and you cannot contain the Spirit’s work. Even if you are enslaved, the Spirit can still give you a song.

Q: Is there something about this art form that lends itself to a daily practice?

I think there’s something about their resonance with human experience, which is why they are sung all over the world, and have been since the late 19th century. These songs connect with the human experience, and in that way, they are connected to daily life. Having some sort of daily liturgy [that draws on them] makes sense, because they do speak to our daily existence.

They’re earthy. They are simple yet deep. They’re not simplistic. If we allow them to work their way into our lives, I think they actually will become a part of our lives and our journeys. It’s like it’s the hymnal of the church in many ways.

They are a part of the life of faith and walk with Christ before God. In that way, they’re fitting for a daily devotional format. We walk with God every day, and these are people who have walked with God through serious, sinful circumstances. We sit at their feet to learn something about God that we might not have known, or maybe something we’ve never considered before.

“Black and unknown bards,” James Weldon Johnson called them, and they’re often forgotten voices even of our day. What do we have to learn from them? [This book is] an offering to say, “Let’s pay attention to what the Spirit might be saying through these spirituals.”

What you have is a great focus on the suffering Jesus in the spirituals, the idea that Jesus’ suffering was our suffering or is our suffering.

Q: The book contains only the words, obviously. Was that frustrating for you as a lover of music?

Often when I do presentations, I’m singing them or having people sing them, because the sound has so much meaning, and not just the mere words on the page. That’s the limitation of a book.

Many people have said to me, “I need to hear these songs.” I am thinking about putting together a kind of audio companion and recording.

Q: Are there places you’d send people whose curiosity is sparked by reading the book?

The University of Denver has something called The Spirituals Project, where you can learn about the spirituals and hear various spirituals.

One thing that’s interesting is [the WPA Slave Narrative Collection of] the Federal Writers’ Project, which was from the early 20th century.

They have some recordings -- obviously, they wouldn’t be of the enslaved -- but sounds of the field hollers and singing or even little preaching moments.

There’s a book called “The Sounds of Slavery.” This is in some ways the closest we can get to the tenor or texture of the acoustics of that time, and I love that.

I use this when I do a class on the spirituals. They’re not necessarily the spirituals, but I do think this is an interesting way to help people get a sense of the mood, the tone, the sounds of that time.

Q: Some of the songs in your book are likely to be very familiar, such as “We Shall Overcome” or “Kum Ba Yah,” but others less so. Tell me a little bit about one of your favorites that people might not know as well.

“The Blind Man Stood on the Road and Cried.” This is one that I first came across in reading Howard Thurman, in his book called “Deep River,” one of the few books in the theological world of reflections on the spirituals.

“The Blind Man Stood on the Road and Cried” is really based on Luke 18 -- there’s a version of [the story] in Mark -- but what’s so interesting to me is the way that in the Bible, the blind man is healed, but in the spiritual, there is no healing. All there is is the crying.

For some, that may be morbid, but I think sometimes all we have is to cry; all we have is to lament. There are moments that we have to keep standing on the road and crying. There isn’t always a resolution, at least in our time.

For me, it gets at this idea of the importance of lament in the Christian life. Sometimes that’s all we have, especially as we travel to the cross, where Jesus himself cries, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

I think there’s just something so honest about that, and so truthful -- so human.

Q: At the end of the book, as the prayer for the day on Holy Saturday, you write, “Word of God, help me to know when to speak and when not to say a word.” I wonder why you chose that as your closing thought of the Lenten season.

On Holy Saturday, what can you say? Holy Saturday is the time for the holy hush. When the holy horror sets in that God has died, there is no good news. There’s no recognition of what’s going to happen early the next morning.

There’s so much emphasis on the word in the Protestant tradition, but sometimes we don’t need to speak. We have to have that discerning wisdom of when we should speak. Words are powerful and shape worlds. The tongue is a fire.

Even for preachers, sometimes silence is the best word and silence is the answer. When Jesus has died -- God has died -- what can you say?