The Rev. Sean Palmer savors the pageantry and performances of Easter almost as fervently as he loves recounting the story of a certain carpenter-turned-itinerant preacher from Nazareth.

In South Carolina, where Palmer grew up, his family color-coordinated their Easter outfits. One year, they were decked out in teal; the next year, in pastel linen. But the highlight of the resurrection celebration was the Easter speech program at Lexington, South Carolina’s New Bethel AME Church, founded more than a century and a half ago.

Palmer, now the pastor of Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church and director of the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Upperman African American Cultural Center, knew that every Easter without fail he would mount the dais and recite something.

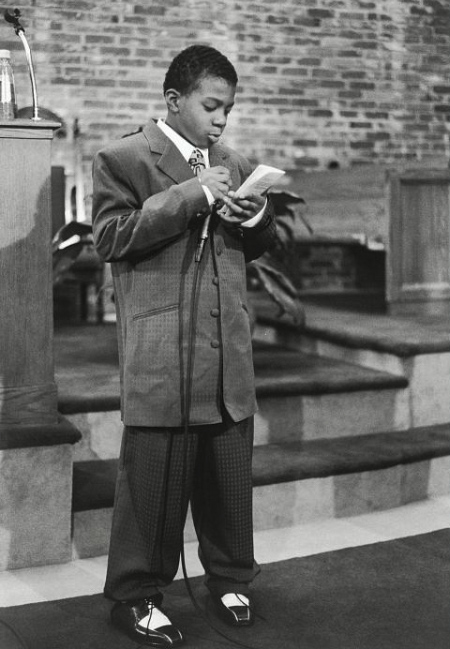

At first, it was a few lines with an obligatory Jesus mention. As he grew older, these performances became lengthier poems and disquisitions, which he wrote himself, about “the reason for the season,” he said.

The Easter speech has historically been an institution within an institution, coaching children in Black oratorical traditions. Earl H. Brooks, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, researches African American expressive culture and sound studies.

He said the Easter speech is one link in “the robust tradition of African American rhetoric, including speeches, toasts [and other forms]. Recognizing the power of language is fundamental to the Black experience in America and across the diaspora.

Tradition and training ground

“In the most current form, that could be the celebration of hip-hop and rap. But before hip-hop and rap, we’ve valued jokes, sermons,” he said. “They’re all part of valuing Black rhetorical sophistication and brilliance,” a tradition studied by scholars from Henry Louis Gates to Geneva Smitherman.

Black celebrities have called it a training ground. Oprah Winfrey said that her first Easter speech, at a Kosciusko, Mississippi, Baptist church at age 3 ½, launched her media career.

In the essay “Beauty: When the Other Dancer Is the Self,” Alice Walker wrote of her 6-year-old self wearing a green dress and new “biscuit-polished” patent leather shoes to deliver a particularly memorable Easter speech. She recalled:

When I rise to give my speech I do so on a great wave of love and pride and expectation. People in the church stop rustling their new crinolines. They seem to hold their breath. I can tell they admire my dress, but it is my spirit, bordering on sassiness (womanishness), they secretly applaud.

The writer E. Lynn Harris began his memoir, “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted,” by recounting Easter 1964. At age 8, he impatiently waited for Beverly, two years his elder, to remember the words of her short speech so he could rehearse his 22-line piece, the longest doled out to any child that year at Little Rock’s Metropolitan Baptist Church.

I wanted to shout out Easter Day is here. Why couldn’t she remember her speech? Even I knew her six-line speech.

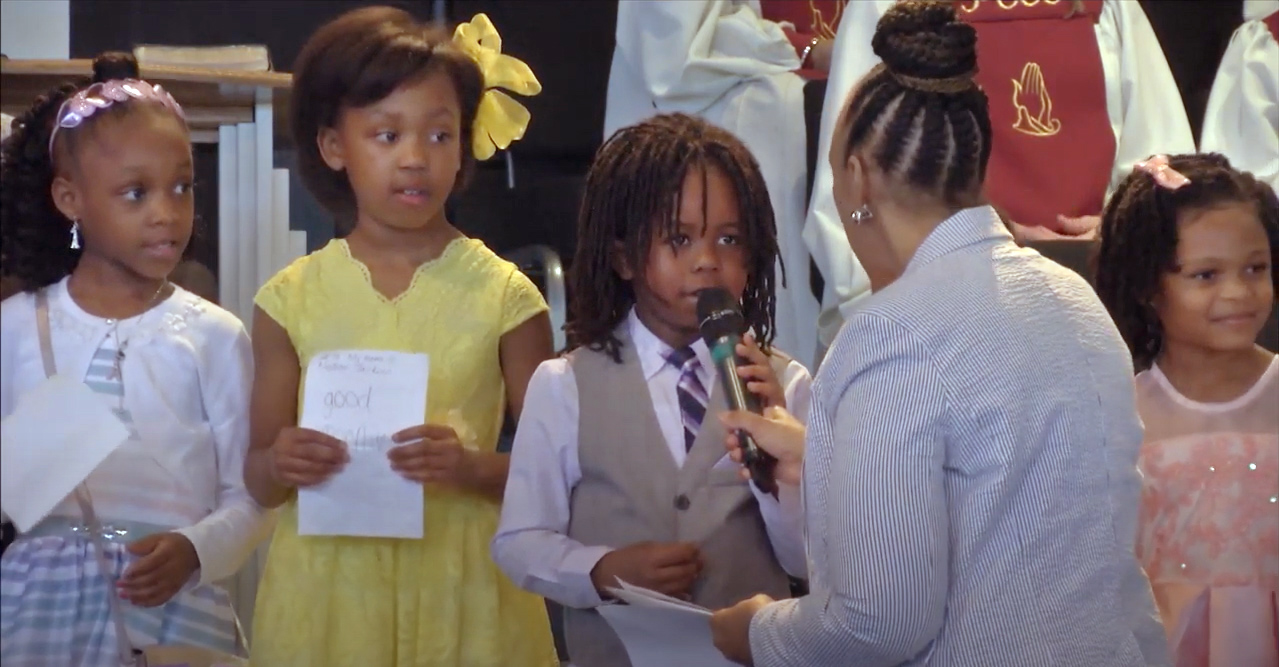

Winfrey, Walker and Harris all participated in the time-honored procession of children, maybe arranged in toddler-to-preteen, stair-step fashion, who share a line, a song lyric from “Jesus Loves Me,” or a bit of Scripture.

How has faith formation from your childhood influenced your life outside church settings?

These brief performances are typically assigned by a Sunday school teacher or church director. Some very small child inevitably forgets his or her lines — or just a single line — after weeks of drilling and rehearsal at home or church. There may be tears and dresses with flounces. But there’s always a congregation that’s willing to feed the young orator that forgotten line and applaud every effort.

The Easter speech is both lesson and African American liturgy, often with a church-specific set of rituals, texts and practices. In the varied milieu that is the Black church — particularly smaller, rural or Southern congregations — it has long inculcated youth with the religious ABCs and introduced them to community, a debut of sorts.

“It’s a ritual that builds community efficacy and connection,” Brooks said. “Even conservatives will acknowledge high levels of alienation and disconnectivity and the loss of communal institutions in this country. But this communicates to you as a child, ‘You can have a platform, too.’ Your voice is literally affirmed in that moment.”

While few children who recite their Easter speeches will go on to become clergy as Palmer did, it’s an all-purpose exercise in leadership and the profession of faith, as well as an informal progress report on children’s development — even if the public aspect of it makes many youngsters quake with annual trepidation.

Who are the nonclergy leaders in your church who make a difference in the lives of others? How does your church acknowledge their contributions?

Command performances

Palmer, 41, sees and hears Easter speeches less and less these days. His congregation, about 70 regular and mostly older members, has few youngsters and doesn’t follow this practice; his son is the only regular attendee under the age of 10.

Still, Palmer misses these literal command performances with the passion of a man who as a small boy would turn his passages into theater.

Aging parishioners, declining religiosity among younger people and overall dwindling church membership (though Black Americans are the most likely of any U.S. racial group to attend church regularly, according to the Pew Research Center) may play a role in the perception that the Easter speech has become an artifact, and further ground has been lost with the growth of megachurches, where “children’s church” often separates worshippers by age.

While Easter speeches aren’t solely a feature of African American congregations, Palmer believes that newer, often multiracial worship spaces are much more likely not to keep this tradition alive. He argues that an apparent overall decline in Easter speeches is doubly troubling when arts and cultural programming that give children the opportunity to be literarily creative are also decreasing.

UMBC’s Brooks agreed, saying today’s youngsters may be pushed toward rote learning for standardized testing, affording fewer opportunities for them to flex creative memory. Brain-powered public presentations have lost out in the age of PowerPoint and other technological assists.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which shut down in-person services in many churches, has also wiped out the practice in some congregations, though others did move it online. And there is also a logistical challenge: in congregations with a large juvenile population, a full slate of Easter speeches makes that holiday service — frequently lengthened by communion and an additional sunrise service — even longer.

What are some traditions that your faith community is resuming post-pandemic, and what are some you will let go?

On the stage

While many Christian communities may opt out of Easter speeches, in those that do provide the opportunity, rarely has participation been optional. Courtney Thomas, a 28-year-old “P.K.” (preacher’s kid) and nonprofit communications professional from Columbia, South Carolina, grew up in a Missionary Baptist church.

Her father also directed Christian education for a denominational association. What’s more, her mother was part of a Toastmasters public-speaking group at work. That meant Thomas was always going to be on the stage.

“I learned how to read, basically, in Sunday school. We did Black history speeches, and we would roll almost immediately into preparation for Easter,” she said.

“Because I grew up in the family I grew up in, we practiced way more than [my peers’ families]. I remember distinctly when my entire family — four of us — would sit on the couch and my mom would drill us on our speeches,” divvying up lengthier pieces on index cards.

Decades later, Thomas can recite one Easter speech on the spot and not miss a beat. She can’t remember when she gave her first one but thinks it was likely before kindergarten; she stopped around age 12 because, newly adolescent, she had decided that Easter speeches were “for babies.”

“You’d see kids as young as 3, still working on trying to make actual words. The younger the kid is that does an Easter speech, the bigger deal it is,” she said.

“You’d call out their name, and that child would take the mic and say, ‘Happy Easter!’ and then curtsy. I didn’t want to curtsy or be in front of the church. Maybe it’s a literacy thing, but the more cynical part of me thinks it’s also about performance and keeping up with the Joneses and using your children to show, ‘My kids aren’t out in street.’”

Palmer also noted, laughing, the scripted and compulsory elements of the Easter speech. One day in the early 1990s, the golden age of hip-hop, a friend tried to rap his contribution — an innovation that wasn’t received well in a church that hadn’t updated its Easter program in some time.

And if an adult “came to church twice and [other congregation members] thought that you might show up on Easter Sunday and you had children, the Sunday school teacher was calling your house or your grandmother’s house or your auntie’s house” to sign up your youngsters for a brief say on Easter Sunday, Palmer said.

Retired educator and librarian Eve Francois directs Christian programming at Christian Unity Baptist Church in New Orleans. She’s run Sunday schools, invited children to her house for Easter egg dying and tea parties, and assigned those Easter speeches. Now in her 70s, she performed her own Easter speeches in her small hometown of Rayville in northeast Louisiana.

“We only got new shoes like maybe twice a year, but Easter was one of those times,” she said. “From the time that I was 3, I grew up reciting poems. That was just part of our upbringing. And what was wonderful about the Easter speech was that even if you messed up, you were in a nurturing environment. No one laughed at you. They would just encourage you: ‘Go on, baby. You could do it, baby.’”

Are there liturgical or formation traditions in your church that would be considered too institutionally sacred for innovation?

Ability and motivation

Using her educator’s eye, Francois said that the art of the Easter speech lies in tailoring passages to a child’s abilities and motivation.

“If a child was reluctant or had difficulty learning their part, there was a little poem I used to use that went something like this: ‘Why are you looking at me so hard? I don’t have much to say. I just came to tell you that today is Easter day.’”

New Orleans-based poet Kelly Harris-DeBerry also attends Christian Unity, and her 9-year-old daughter, Naomi, will recite her Easter speech this month under Francois’ direction. It will be the first time since spring 2019 that the church will have in-person Easter speeches and a parade.

Naomi has long since outgrown her Easter dress from that year.

Performing an Easter speech “is very exciting for me this year in particular, because I haven’t been able to do an Easter speech since I was 6,” Naomi said. “I guess I did not understand all the way back then, but I feel I can have more of a brave and bold Easter speech [this year].”

She has the elements of the Easter speech down pat: introducing herself, welcoming the congregation with a shoutout, delivering a short religious homily with confidence. And before all that happens, pulling together a look befitting the occasion. “Girls in particular have to get their hair done the night before, dress, tights, hat, and it’s kind of fun to pick out those things,” she said.

Naomi’s mother especially cherishes the women like Francois — often legendary long-term Sunday school superintendents — tutoring girls like her daughter now, and herself decades ago.

“I think back on all those Easter speeches, and even currently in my community of faith, there was always a presence of a Black woman educator somewhere. They were embedded inside of church, like pre-speech or debate teams, teaching the building blocks we needed about communication and presentation,” Harris-DeBerry said.

Growing up denominationally in the Church of God in Christ, she said, she’d receive her annual Easter assignment on a tiny slip of paper early on. That paper got larger and larger as she grew older, and her mother would fold it carefully and stash it in her purse.

What practices from your church connect people across generations? What are the activities everyone remembers years later?

“My parents were serious about it. I would practice in the living room, and my dad would give me a brush and a comb to hold [like the mic]. He’d say, ‘Hold it up to your mouth.’ ‘Speak up.’

“My mom would be cooking in the kitchen, and she’d say, ‘Start your speech,’ just randomly, and give me the first line. … And my dad wasn’t just satisfied with me doing [a simple] Easter speech. He was like, ‘You’re going to do an Easter speech and name all the 12 disciples.’ It was about Black excellence.

“I think it was the precursor for me being a poet, because there’s a certain way, even now, I hold the mic. If I’m in front of a podium, there’s a certain way that I check the sound of my voice. I don’t need a sound guy to adjust my voice; I can almost hear it. All that comes from being in the church and Easter speeches. It began with the brush and the comb.”

Questions to consider

- How has faith formation from your childhood influenced your life outside church settings?

- Who are the nonclergy leaders in your church who make a difference in the lives of others? How does your church acknowledge their contributions?

- What are some traditions that your faith community is resuming post-pandemic, and what are some you will let go?

- Are there liturgical or formation traditions in your church that would be considered too institutionally sacred for innovation?

- What practices from your church connect people across generations? What are the activities everyone remembers years later?