When Nashville’s Christ Church Cathedral was looking to commission a new work in 2015, Marcus Hummon was the obvious candidate for the project. The self-avowed “theater nut” had previously written an Easter cantata for the historic congregation on the passion of Christ. This time, the cathedral’s request was simply that the work be inspired by “the prophetic,” however Hummon might understand that.

“It was that wide open,” Hummon said.

In response to the cathedral’s ask, he turned to the words of abolitionist and activist Frederick Douglass.

“‘The prophetic’ is a loose term these days, when not many people are churchgoers or familiar with Christocentric language,” Hummon said. But to him, the term is less about foretelling events than about being an intermediary between the divine and the nation.

“From my Judeo-Christian background, I think of [Frederick] Douglass as a Jeremiah,” he said. “The Almighty has something compelling to say, and it needs to be said. The prophet stands between.”

That initial work eight years ago set in motion a collaboration with Charles Randolph-Wright that has produced the now Broadway-bound “American Prophet: Frederick Douglass in His Own Words.”

“American Prophet” won an Edgerton Foundation New Play Award and was named to The Washington Post’s 2022 Top 10 Best of Theater list, in the esteemed company of Pulitzer and Tony winners and Broadway revivals.

According to Post critic Peter Marks, the musical “brought history exuberantly into three dimensions …, a fitting tribute to a man who gave voice to so many with no way of amplifying their own.”

Spiritual power of music

How would your faith community define “the prophetic”? How would you?

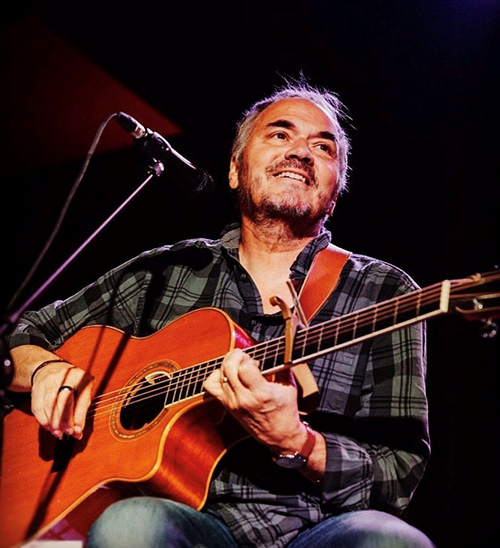

Not every country music writing room includes songwriters penning catchy lyrics and memorable guitar licks while pondering the meaning of the prophetic. But then not every Nashville musician has a theological background and a deep interest in faith and social justice like Hummon. He grew up attending D.C.-area churches with his diplomat parents, going on to study at Vanderbilt Divinity School. And he’s married to a priest.

The singer-songwriter, composer, playwright and instrumentalist takes his faith seriously and has made a career out of harnessing the power of music to frame words and messages.

In one of his best-known songs, “Bless the Broken Road” — made famous by Rascal Flatts — which won the 2005 Grammy for best country song, religious overtones are clear. In other tunes, like those that won him five #1 BMI songwriting awards, including hits for The Chicks, Tim McGraw, Wynonna Judd and others, the references are less overt but still there.

“As a songwriter and composer, I am writing the gospel as I understand it,” he said. “That’s always what’s going on, and music is the authentic way for me to express it. I’m grateful that my folks dragged me to church. When we’re given these stories as children, they go in really, really deep. For me, it’s about the love of community, and coming together to speak a word of peace and of the power of love in the world.”

And that too, he believes, is the spiritual power of music. “It can transport us. Particularly if you let it happen, if you let it wash over you. I think of it as living poetry.”

Poetic genius

Douglass’ language moved Hummon, who had dug deep into Douglass’ autobiographies and read numerous other scholarly works about him.

“His words rise to the level of poetry,” he said. “Frederick was a genius who intuited the moral arc of the nation and knew what we must become.”

Hummon initially wrote a 24-song cycle called “Frederick Douglass: The Making of an American Prophet,” which was performed at the cathedral and subsequently at Vanderbilt’s Benton Chapel.

While the work was well received, Hummon knew it had more potential. He also knew he needed help to take it to the next level. “It was bigger than me,” he said.

“When I met Charles, that’s when it really took off,” Hummon said, speaking of the acclaimed film and theater director, producer and playwright Randolph-Wright, whom Hummon calls “Broadway royalty.”

Randolph-Wright’s impressive credits include performing in the original cast of “Dreamgirls,” directing Broadway’s “Motown: The Musical,” and launching a national tour of “Porgy and Bess” for the opera’s 75th anniversary in 2010 — in addition to the extensive list of plays he has written and television he has produced.

When Randolph-Wright got a cold call suggesting that he go meet an artist in Nashville who was working on a Douglass musical, he was skeptical.

“I went because I had relatives to visit in Nashville, but I had no intention of getting involved in this project and had never thought of Frederick Douglass in terms of a musical. I mean, how can you take these extraordinary speeches and distill them to song?” he said.

Randolph-Wright didn’t even look up Hummon’s bio before they met.

“I just knew he was some white man in Nashville and thought, ‘Well, what kind of appropriation is this?’” he said. “But when Marcus played me the first song, it literally went through my body, this visceral response. His music felt prophetic, and I realized this is the exact way to express Douglass’ journey.”

Beyond those held up in biblical narratives, who are the people your congregation reveres, and why?

Randolph-Wright signed on as director and co-writer of what would become “American Prophet.”

The two set about reenvisioning the work, incorporating more of Douglass’ relationship with Lincoln and, in consultation with Douglass family descendants, bringing the character of Anna, Douglass’ wife, to the fore in a way that had never been done before.

“They were married 44 years and had five children. Without Anna, there would be no Frederick. She ran the Underground Railroad, she did their finances, but history only tells us that she was illiterate,” said Randolph-Wright. “We literally gave voice to her. That’s the magic of a musical.”

Hummon wrote all the music and lyrics, based directly on Douglass’ own words, in the style of “a contemporary hymn, that deepest expression of something that is praising, or a lament, balanced with some levity, some groove,” he said, noting that only one song from his original work ended up in “American Prophet.”

Meanwhile, Hummon and Randolph-Wright collaborated on the book, and Randolph-Wright did the casting, tapping Cornelius Smith Jr. to star as Frederick and Kristolyn Lloyd as Anna.

“Having a great director and co-writer made all the difference,” said Hummon. “Charles is really the point of the spear for this production. He’s pushing me all the time, saying I need more here, need more there. And he was generally right.”

Timely pause

While the pandemic delayed the slated 2020 opening, the eventual July 2022 premiere at Arena Stage — in the heart of the nation’s capital and in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and Jan. 6 and all that the country had been through — felt even more timely.

“Audiences got to hear how relevant Douglass’ words from the mid-1800s still are and how they resonate, and how depressing it is that we’re still fighting those same battles,” Randolph-Wright said.

“For me, it is uplifting. It challenges the audience to agitate, to not sit back. And that’s where faith comes in. How did we find joy in the middle of devastation? That’s our responsibility as artists, to help in that discovery.”

The show is for all Americans, regardless of political leaning, Hummon said.

“Here’s a man who had every right to hate this country but found a way to love it. He believed in the Constitution as the path to justice and convinced Lincoln of that,” he said. “With white supremacy and anti-democratic forces on the rise, Douglass’ language feels like it is speaking to us right now.”

Broadway bound

Uplifting ovations became routine at every show. Audiences applauded, tickets sold well, and critics, uniformly, wrote positive reviews. “That never happens,” Randolph-Wright told his collaborator.

Acclaim for the musical has drawn the attention of Broadway, with talks currently in final stages for an “American Prophet” three-month run at New York City’s Roundabout Theatre and then in London’s West End, “where Douglass was beloved,” Hummon said.

After that, their real hope is for the show to go on national tour and eventually be licensed for schools and regional theater across the country. That’s quite a journey for an idea sparked by mulling on the prophetic.

“It’s pretty cool that this all began in a small church in Nashville and, hopefully, will move on to the world,” said Hummon.

How might people of faith help identify and magnify the voices of prophets who have been silenced, overlooked or ignored?

Randolph-Wright shares his collaborator’s hopes and delight.

“I came in with zero expectations, so I’ve been blown away, both by how Marcus’ music moves me — he’s truly a man of faith, and that comes through in every note — and also by this moment,” he said.

“Little did I know how imperative it was to tell this American story in this way, especially now with what’s happening with not teaching history and critical race history.”

Then again, Randolph-Wright reflects on something he learned as a religion (and theater) major at Duke University.

“One does not know how the prophetic happens; it comes in unexpected places and affects you in unexpected ways. That’s from Professor [John] Westerhoff!” he said. “You can’t plan prophecy.”

‘Words matter’

United States Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was newly appointed to the court when she was among several dignitaries who attended opening night at Washington’s Arena Stage last July for the musical’s world premiere.

Along with the sold-out house, Jackson cheered and applauded as the musical’s rousing finale, “We Need a Fire,” brought the audience to its feet. During the ovation, many people started singing along.

“There was so much energy, so many people joining the chorus. It felt like church or a political rally,” said Hummon, who had hoped for precisely that kind of reaction.

Are there ways for your congregation to support the arts that could benefit the wider community?

Jackson was stirred. “Because the show really is that good, I went to see it again a few weeks later, bringing my law clerks and staff,” she said, highlighting the musical’s enduring impact on her during a commencement speech to the Boston University School of Law last May, some 10 months after she’d first seen the production.

“American Prophet,” she told the cohort of newly minted lawyers, demonstrated that words matter. According to Jackson, the effective way in which the show repeated certain of Douglass’ phrases, perhaps first “in a speech, then in a conversation, then in a song, and then in a reprise version of that song,” allowed the show’s message to resonate with listeners “in a nuanced, complex and meaningful way.”

So, she emphasized to the graduates, “Words matter, and … the framing does too. It’s not just what you say that leaves an impact; it’s also how you say it and how you get your message through.”

Where is your church finding energy? How can that be cultivated further?

Questions to consider

- How would your faith community define “the prophetic”? How would you?

- Beyond those held up in biblical narratives, who are the people your congregation reveres, and why?

- How might people of faith help identify and magnify the voices of prophets who have been silenced, overlooked or ignored?

- Are there ways for your congregation to support the arts that could benefit the wider community?

- Where is your church finding energy? How can that be cultivated further?