If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call, chat or text 988, a national, 24-hour service.

When psychologist Karen Mason managed the Colorado Office of Suicide Prevention in the early 2000s, she wanted to engage faith leaders to help educate the public and respond to warning signs of crisis.

But her research since then has revealed a paradox. Though pastors are uniquely positioned to help prevent suicides, they’re often hesitant to embrace the role.

“Clergy are very reluctant to talk about the topic because they don’t know what to say and they’re afraid to say the wrong thing,” said Mason, now a professor of psychology at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and the author of “Preventing Suicide: A Handbook for Pastors, Chaplains and Pastoral Counselors.”

Faith leaders’ silence, no matter how well-intentioned, comes at a price. It can reinforce stigma associated with suicidal thinking, Mason said, including the assumption that contemplating suicide signals a weak faith. When people feel that their struggles can’t be disclosed, even at church, social isolation and risk of suicide can increase.

Pastors have “a moral responsibility to help this person sort through, ‘What other options do [I] have besides death?’” Mason said.

Suicide is increasingly recognized as a prevalent and largely preventable problem. The U.S. suicide rate increased by 30% from 2000 to 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s now the nation’s 12th leading cause of death, responsible for the loss of almost 46,000 lives in 2020.

When clergy look out at the pews and see middle-aged faces, they’re looking at the group most likely to need help: 80% of suicide deaths occur among men and women ages 45 to 54. Rates across age groups are especially high for certain demographic groups, including men, Native Americans, LGBTQ folks, rural dwellers, farm workers, military service members and veterans.

Efforts are now proliferating to help pastors rethink assumptions, prepare for conversations about suicide, and recognize that they don’t have to be therapists in order to discuss people’s hopeless feelings and influence their life-and-death choices.

Many pastors express a feeling of powerlessness, said Michelle Snyder, the executive director of Soul Shop, a nonprofit that equips faith leaders to train congregations in ministering to those pondering suicide.

“To which I say ‘no’; I reject that. I think pastors have the power of persuasion,” she said. “So leverage your position for suicide prevention.”

Resources and training

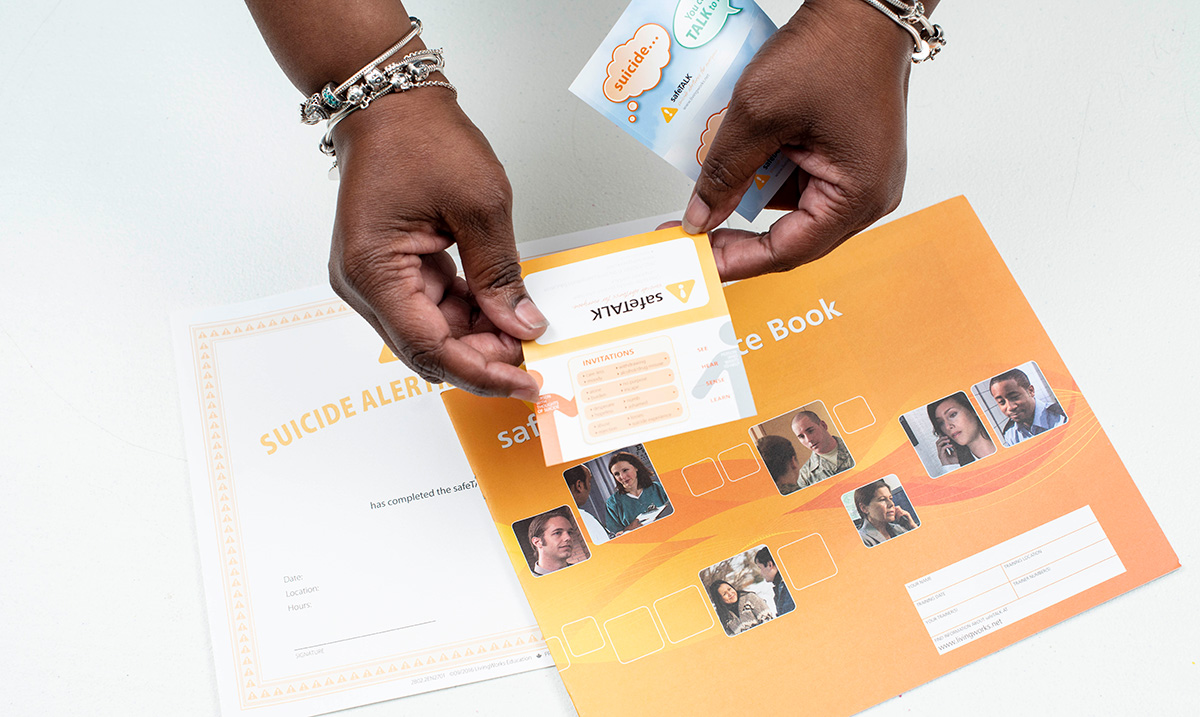

Resources have been expanding to help pastors do that leveraging. For example, in October 2020, the LivingWorks company launched LivingWorks Faith, a self-paced online program that guides faith leaders in how to intervene, minister to the bereaved post-suicide and promote purposeful living.

Those seeking to go deeper can attend the company’s two-day in-person program in Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), which has been used by the U.S. military for more than 20 years.

Soul Shop offers a one-day in-person workshop for faith leaders that covers how to help congregants have conversations about suicide and how to solicit testimonies from those who’ve been suicidal in the past.

In August, it announced a new one-day workshop specifically for pastors, church staffers and lay leaders in the Black church. The Soul Shop for Black Churches training works to address the recent rise in suicides among Black people. The suicide rate for non-Hispanic Black Americans jumped 3.5% from 2019 to 2020, even as the general population saw a 3% decline in the same period.

And in July, the national suicide prevention hotline got a new, easy-to-remember number: 988. This gives pastors another tool to use in crisis situations, Mason said. If someone calls expressing thoughts about suicide, a pastor can keep the person on the phone and they can call 988 together.

On what topics are you silent? What is the price of that silence?

In trainings, pastors learn to spot warning signs. Some are actions, such as giving away all of one’s personal possessions, not showing up for work or nonstop sobbing. Others might be comments such as, “I think the world would be better off without me.” Major setbacks in a person’s life, such as a divorce, bankruptcy or public humiliation, can also be associated with heightened suicidal risk.

Then what? When a pastor learns that someone is contemplating suicide, next steps could involve removing the intended means, connecting the person to mental health services and promising to follow up with a check-in call soon. All are doable by pastors with no specialized suicide prevention training, experts say.

When clergy hear someone say they're considering suicide, they are not legally obligated to report the suicidal person or to take other preventative actions unless they live in a state that requires such steps, according to Mason. She added that she does not know of any states that require clergy such reporting.

How can you foster a sense of belonging in your congregation?

Guns and suicide

Removing the means that a suicidal person plans to use can be crucial, especially if the plan involves a gun. That’s because guns are so lethal.

They’re used in fewer than 5% of suicide attempts, yet they’re responsible for more than half of all suicide deaths, according to CDC data. And 54% of gun deaths are suicides, according to 2020 data from the National Safety Council, a nonprofit focused on eliminating causes of preventable death.

Mason points out that guns are different from other methods because they don’t allow a person to reconsider.

“If you were to swallow pills, you could say, ‘Gosh, this is not what I wanted to do,’ and you could call 911. But with guns, you don’t get a second chance, and your reasons to live don’t get a chance to emerge.”

This is an area where pastors can make a difference.

Do the questions you ask invite honest responses?

Being effective starts with asking directly, “Are you considering suicide?” That’s a common question for the Rev. Kenya Procter to ask in her ministry as executive pastor at Ambassadors for Christ Worship Center in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Raising the topic doesn’t make suicidal thinking more likely, experts say, but rather creates a safe environment for people to express their desire for help. Procter also trains pastors in suicide prevention through the LivingWorks ASIST program, which emphasizes the need to be clear and direct.

The reason? If she were to ask something indirect, such as, “You’re not thinking about doing something crazy, right?” she’d be prejudging the response, she said. Because a person who answered “yes” would be admitting to lunacy, he or she is apt to say “no” instead, even if the answer isn’t sincere. Asking the question directly makes a clear and honest response more likely.

If a person answers “yes” and is a gun owner, Procter said, she might suggest storing the guns temporarily with the police department, which will return them when the person is ready. And for anyone possessing guns, whether presently in a crisis of suicidal thinking or not, she suggests keeping guns locked.

“The three seconds that it takes to unlock might be the three seconds that deter that person from using that firearm,” Procter said. “Because then you have to get the key. You have to put the key in the lock. And people with thoughts of suicide are not always thinking rationally. … So those three seconds could make the difference.”

Procter speaks as someone who’s felt the pain of suicide’s ripple effects. She and her husband, Fallon, had a mutual friend, Jay, whom they’d known when Fallon and Jay were soldiers stationed at Fort Bragg. Jay always seemed to have something about him that “never sat right, but I couldn’t put my finger on it,” she said. They later learned that Jay had been involved in another person’s death and eventually killed himself.

When she got an opportunity to work in suicide prevention, she embraced it as a chance to help others do what she had not been equipped to do for Jay, such as know which warning signs to look for.

In talking with congregants, it’s important to convey that God is near, according to Glen Bloomstrom, the director of faith community engagement for LivingWorks. Isolation can intensify thoughts of “My life is worthless; I don’t belong” and needs to be met with messages of love.

“The healthy way to talk about this is …, ‘We are here for you,’” Bloomstrom said. “‘Don’t isolate. Speak with us. We can get you help. You are very valuable to us. You are loved as part of our congregation.’”

In these situations, pastors don’t have to guess at what to say. The hotline can guide them in the moment as they speak with a suicidal person and conference in 988.

“Let 988 help the clergyperson or whoever is calling figure out the right thing to do next,” Mason said. “The situations differ so much. It is hard to give advice [for faith leaders] that’s going to blanket every situation.”

Pastors can be most effective when they aren’t acting as salvation agents but rather as equippers of a team effort to encourage life-affirming choices. For instance, a pastor who knows a responsible gun owner might ask, “If the situation arises, would you hold a gun for someone temporarily?”

Then if a crisis arises, the pastor can suggest to the suicidal gun owner, “How about if so-and-so, whom you know and trust, holds on to your guns for a while until you’re ready to have them back?”

Cultivating community and hope

In crisis situations, disabling a suicide plan sometimes happens by moving the person to a new environment, such as a hospital emergency department, where mental health resources are available and firearms are not.

How can you form and equip a team to encourage life-affirming choices in a crisis?

That’s the approach used by the Rev. Leon Sampson, an Indigenous Episcopal priest at Good Shepherd Mission on the Navajo reservation in Fort Defiance, Arizona.

When they say they want to hurt themselves, “they want help,” Sampson said.

“The first step we’ll do is take them to the emergency room. We tell them, ‘This person has said they want to hurt themselves.’ Through the Indian health system, they will receive counseling and be able to get the resources they need.”

But Sampson also knows that contributors to despair on the reservation are unfortunately common, including abuse, cyclical poverty and lingering effects from past traumas.

As an antidote, Good Shepherd hosts programs in which teens and young adults learn Navajo traditions, from agriculture and cooking to spiritual practices and the Navajo language. Sampson helps them proudly share their heritage and identity by inviting them to address church groups visiting on pilgrimage or mission trips.

As part of cultural pride building, Sampson lifts up appreciation for responsible gun ownership as a component of Navajo culture. He traces it to the tribe’s long history of sending men and women into military service and having guns for protection and hunting.

With this honorable gun-owning tradition comes a duty, Sampson tells young Navajos, to store firearms and ammunition responsibly.

“Gun education and gun safety have been part of the community,” Sampson said. “Very rarely do you hear of a teenager [here] self-inflicting harm with a gun. I think that’s because of the history of families. … They have a deep understanding of how to handle and keep guns.”

Theology, taboos and false assumptions

Shaping culture to support choosing life might look different on the reservation, on a Midwestern farm or in a coastal city. But in each setting, the pastor is drawing on a frequently used skill.

Pastors shape worlds by weaving narratives and elevating particular values in community life. In suicide prevention, that means grappling with how suicide has traditionally been viewed through a theological lens as well as parishioners’ deeply ingrained taboos and assumptions.

Suicide is complicated for pastors, because it’s loaded with theological baggage. It’s been understood as sin, self-murder, cause for exclusion from Christian cemeteries, even an automatic ticket to hell. Such concepts presume that the final act was a grave misdeed and left no margin for repentance or forgiveness.

Such ideas trace back in part to Augustine of Hippo, the fourth-century African bishop who taught that life is a divine gift to be cherished and put to use, not something to extinguish in hopes of entering a better world in the hereafter.

New thinking about suicide and morality is needed to foster more compassion toward those struggling without hope, according to the Rev. Rhonda Mawhood Lee, an Episcopal priest in the Diocese of North Carolina. With support from a Louisville Institute grant, Lee is writing a book that develops a new theology of suicide.

Lee has been touched by suicide directly. Going back generations, several members of her family have taken their own lives. Her mother made multiple attempts at suicide while Lee was growing up before dying by suicide in 1995, when Lee was in her 20s.

She’s careful with her terminology, using “died by” rather than “committed” suicide, because the latter connotes sin and crime.

“Saying that suicide and other complicated ills like substance use disorder reveal the fallen nature of our world does not have to mean assigning culpability to people who kill themselves, or sitting in judgment of them,” Lee said in an email.

“It does mean we can lament suicides, have a range of feelings about them, and do what we can to prevent them.”

In working through the repercussions of her mother’s suicide, Lee has spent years researching her family history and noticing patterns that help her understand it.

A number of theological ideas about suicide need reexamining, she said. The one who dies by suicide shouldn’t be seen as unsavable, she said, because that would “tie God’s hands” and leave no room for grace. Instead, suicide, while always lamentable, should be seen in light of conditions that might have driven the person to desperation.

Taboos around suicide are tenacious, and today’s work involves probing which ones, if any, still serve a useful purpose. The taboo describing suicide as self-murder is too harsh and diminishes compassion toward those struggling with suicidal ideation, Lee said. But the general cultural taboo against dying by suicide might help prevent suicide in some cases by marshaling social pressure to choose life instead, she said.

As pastors gain appreciation for how much they can do to prevent suicides, they’re discovering how much needs to be done on fronts ranging from pastoral care and preaching to theology. Wherever they begin, it’s with growing conviction that this is the church’s work to do.

“We’re trying to demystify the idea that [suicidal thinking] is somehow this untouchable thing that is so medical that it requires the professionals,” Soul Shop's Snyder said. “In fact, what it requires is communities that can respond with community and with hope.”

What do your congregation’s theological ideas about suicide say about God?

Suicide prevention resources

Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call, chat or text 988, a 24-hour service for anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress.

Questions to consider

- On what topics are you silent? What is the price of that silence?

- How can you foster a sense of belonging in your congregation?

- Do the questions you ask invite honest responses?

- How can you form and equip a team to encourage life-affirming choices in a crisis?

- What do your congregation’s theological ideas about suicide say about God?