On a hot Saturday afternoon, 200 adults and children are scattered on a grassy field for the singing of the national anthem, their hands over their hearts as a recording of “The Star-Spangled Banner” blares from a speaker.

A moment of silence follows -- on this July day, in memory of Master Sgt. Jonathan Dunbar, who died in Syria in March.

Then Sam Barnett, a veteran who spent his career in the U.S. Army Special Forces, speaks into a microphone from a wooden pergola.

“This place is for you,” he says, scanning the crowd and the fields. “You don’t have to ask, ‘Can my child do this?’ Please tell people about Rick’s Place. Come out and enjoy!”

Running and shrieking and laughter ensue, as scores of children from tots to teens descend on play stations scattered across the park’s 50 acres of green space, 5.5 miles from Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Some divide into teams, pick up water balloons, and at the sound of “Go!” begin hurling them across the field at each other. Others gear up for a water kickball event. In the midst of the action, a foam machine spews hypoallergenic suds as kids in bathing suits swarm underneath, lost in clouds of billowy white bubbles.

Rick’s Place, a 4-year-old park established to provide recreation and community for military families stationed at Fort Bragg, has come into its own. Named after a fallen soldier -- Sgt. 1st Class Rick J. Herrema, who died in Iraq in 2006 -- the park and its programs offer a new model for helping military families relieve stress, reconnect to one other and build relationships.

How can your organization help people flourish in difficult circumstances?

“Everybody struggles with bad things happening,” said Allegra Jordan, the executive director of the Rick Herrema Foundation, which runs the park. Jordan, whose father served in Vietnam and who holds an MBA from Harvard, came on a year ago.

“We try never to deny that reality. Someone died to make Rick’s Place happen. But in the midst of that, how do we prove to ourselves that we can flourish, even with this reality? How do we move from war to peace, from high-difficulty times to mundane family life?”

Rick’s Place has Fayetteville’s only free kids zip line, situated along an obstacle course. There are raised flower and vegetable beds, tiny lending libraries stocked with books for children and young adults, fire pits, walking trails, playgrounds, and plenty of open space to run free.

On special occasions, there are horses or goats or therapy dogs, archery classes, paintball games and cooking demonstrations.

“We want to take apart the stigma and really just provide families a place where you can go decompress,” said Barnett, the foundation’s president, referring to the shame many soldiers feel in admitting that they need social support.

While the Army offers several programs to help military families cultivate healthier habits, those require soldiers to step up and self-identify. Rick’s Place has no formal ties to the military, no paperwork and no fees.

“You can be who you are as a family unit and engage as a family in great activities outdoors,” Barnett said. “Meet out there. Fellowship. Create a platform that is separate and distinct from the stigma associated with [military] programs.”

From idea to reality

The idea for Rick’s Place took shape during a February 2014 snowstorm that kept Angelina Woehr and her husband, a career soldier, confined in their Fayetteville home for 48 hours.

A day earlier, they had gone with a real estate agent friend to inspect a 26-acre plot of land. The couple had always wanted to buy property where they and their friends could get away and relax from the stress of deployments.

The Woehrs began by thinking of ways to help themselves and expanded the mission to include an entire community. Are you thinking big enough?

But cooped up at home during the storm, they debated whether this property was too big for them and their closest friends. Perhaps it could serve a larger purpose.

“We thought, ‘What do we need most?’” says Woehr’s husband, who asked that his name not be used. “We need a place to connect. We need a place where we come back from deployments to figure out what our new normal is.”

Fort Bragg is the country’s largest Army base, serving a population of 52,000 active-duty soldiers, as well as thousands of reserves, civilian employees, contractors and retired military personnel.

Each spring, about 30 percent of the base turns over as soldiers and their families are deployed, retired or reassigned to other bases.

The constant moves and repeated deployments take a toll. About 50 percent of active-duty soldiers are married, and about 40 percent have children. Staying connected to family, both during and after deployment, is a major challenge.

“It’s tough to say goodbye to a service member that’s leaving,” said Pamela Wall, a psychiatric nurse practitioner at Duke University’s School of Nursing who served nearly 20 years in the Navy and helped Rick’s Place develop a satisfaction survey. “It’s even tougher when they come home.”

But as Angelina Woehr discovered, there are ways to reconnect after a monthslong deployment. One year, her husband planted her a vegetable garden; another year, he built her a studio for her artwork.

“Through our process, we learned that planting things, building stuff -- these are all things that are very different from what he does for work, but he really enjoys it,” she said.

Are there ways you could help people that don’t fit into the usual categories, such as “therapy” or “ministry”?

“We would never have used the word ‘therapeutic,’ but it was a form of therapy. He was giving me something, as a husband, as a friend. He was providing something for me, and that was really cool for him. But he was also enjoying the process. He was using tools and getting his hands dirty. And we thought, ‘We can’t be the only ones,’” she said.

By the time the snowstorm had subsided, the couple was eager to talk about their vision with other military couples and with their pastor, the Rev. Jonathan Fletcher at Fayetteville’s Manna Church.

Though they were regular churchgoers and were motivated by the Christian ideal of servant leadership, they didn’t want their retreat to serve only Christian military families but all military families.

Within a short time, the land was bought, teams of church volunteers had cleared brush and old horse stables, and a core group had formed to create the first board of directors. (Fletcher, their pastor, sits on the board.)

The couple also knew they wanted to name the park after friend and mentor Rick Herrema, who died in Iraq in 2006. Herrema was an especially caring and conscientious person who took his work and friendships seriously.

With a nonprofit designation on the way and 26 additional acres purchased soon thereafter, the idea was becoming a reality. From the start, the initial group thought that if they were successful, the park concept might be replicated elsewhere.

The reintegration challenge

America’s military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on for 17 years. More than 3 million service members have served in those campaigns, and 7,000 have died.

The toll taken on the lives of those who have returned has been grave. Many suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Others struggle with explosive anger, alcoholism, pornography addiction, divorce and thoughts of suicide. Recent studies have shown that the suicide rate among active-duty personnel has been rising over the past decade -- now at 20 per 100,000 for active-duty service members, vs. 13 per 100,000 for Americans generally.

Are there creative strategies you could employ to serve a demographic group in your community, as Rick’s Place serves military families?

“There’s an expectation that that reintegration would happen seamlessly and flawlessly and without a whole lot of effort, and that’s just not the case,” said Barnett, the foundation president. “You come back and you’ve changed. The culture of your home has changed. This person you’re married to has changed.”

It’s this particular challenge that Rick’s Place is designed to address.

While the Army offers soldiers suffering from PTSD various retreats in Alaska and Montana and California, it’s hard to win one of those plum vacations, and they are offered infrequently -- once every couple of years. Rick’s Place is designed for the times in between.

Its chief advantage is its proximity to Fort Bragg. Soldiers can drive to the park at lunchtime, sit at a picnic table under the shade of a tree, and be back on base within an hour. So far this year, the average monthly attendance is 400, up from an average of 300 in 2017.

Since receiving its nonprofit designation in 2014, the foundation has added land and staff. There’s an old clapboard house where meals are shared and administrative staff offices are located. There’s also a large storage shed and a woodworking workshop.

Among the park’s signature programs:

- Messy Mondays, weekly art experiences for preschoolers that incorporate sensory as well as visual play, using squirt guns or shaving cream and dyes to paint, for example.

- Work Days, monthly volunteer gatherings for soldiers that offer opportunities to clear land, mow grass or work on various carpentry projects. Child care and lunch are provided.

- Fun Days, monthly family-friendly events featuring a communal lunch followed by activities such as concerts, paintball and Nerf battles, water games in the summer, and marksmanship, archery, soccer, and volleyball in cooler weather.

- Homefront Hearts, weekly mentoring meetings for military spouses with topics such as budgeting, cooking, parenting and self-care. Child care is provided.

All the programs are free, including meals. Donations and grants support the ongoing work and staff salaries. Several church groups volunteer there as well, including members of Rick Herrema’s home church, who come down from Michigan twice a year for weeklong sessions to help with larger projects such as building sheds and wheelchair ramps.

Could you offer simple opportunities for people to form friendships and experience “playful joy”?

A user survey completed this year by 54 Rick’s Place participants offered proof that the park is succeeding in its mission. Most of the respondents said the activities weren’t the critical draw. Rather, what appealed to most of them was a space to be outdoors with each other and to form friendships.

“That was an aha! moment for us,” said Jordan, the executive director. “We don’t have to have the best horse program. What we need to do is consistently make sure that we can provide a nutritious meal and a few activities for kids to gather around to create that sense of playful joy.”

Fostering community

On a recent Fun Day at Rick’s Place, Jordan greets as many people as possible, as is her habit.

“I heard you had a scare this week,” she says to one woman. “Are you feeling OK?”

“Awesome dogs! Thanks so much for coming out. It’s good to see you. I’m the executive director, Allegra,” she tells a group of three young people as they approach with puppies on leashes. They are part of Continuing the Mission, a nonprofit that provides service dogs for veterans living with PTSD, and they often bring puppies to Rick’s Place to let the kids play with them.

This warm welcome is one of the reasons people like Rick’s Place.

Amy Covey, the wife of an active-duty soldier, washes dishes in the park kitchen after lunch. She and her family just returned from two and a half years at Fort Drum in upstate New York, but she said she immediately found her niche at Rick’s Place.

“It’s so important to have a place to go to feel loved and appreciated,” Covey said. “They do it very well here.”

The degree to which the park can foster community and wholesome family routines off base may be its biggest asset. Though there is talk of replicating Rick’s Place in other cities with large military bases, so far this site is the only one.

Kirsten Brunson, a retired military judge whose husband is still on active duty, comes to Rick’s Place with her son, who loves to simply run.

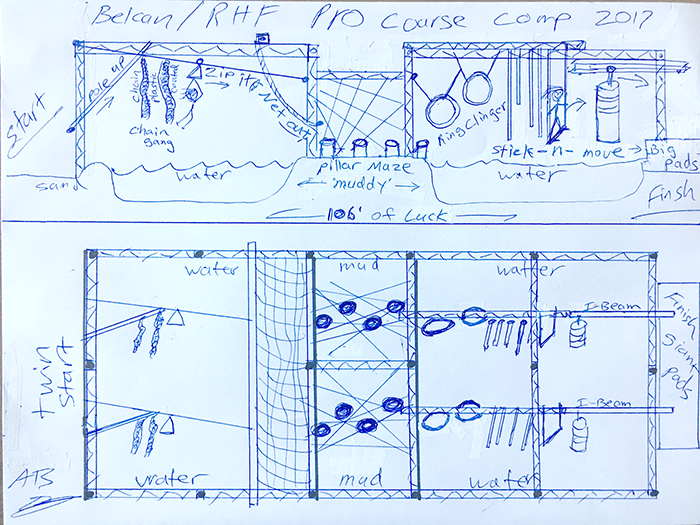

Last year, Brunson volunteered to oversee an adult obstacle course at Rick’s Place and has wanted to remain involved ever since, because the people, she says, are “phenomenal.”

“There are wonderful programs at Fort Bragg for soldiers and their families,” she explained. “But it’s on Fort Bragg. You’re around soldiers all day. This gets you away from all of that, so you can take a deep breath and relax. You’re not going to run into somebody in uniform. You’re not worried about who outranks you.

“You’re just out here with your family, enjoying nature, enjoying each other in a peaceful setting. It’s built as a respite, and it really is.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- How can your organization help people flourish in difficult circumstances?

- The Woehrs began by thinking of ways to help themselves and expanded the mission to include an entire community. Are you thinking big enough?

- Are there ways you could help people that don’t fit into the usual categories, such as “therapy” or “ministry”?

- Are there creative strategies you could employ to serve a large group of people in your community, as Rick’s Place serves military families?

- Could you offer simple opportunities for people to form friendships and experience “playful joy”?