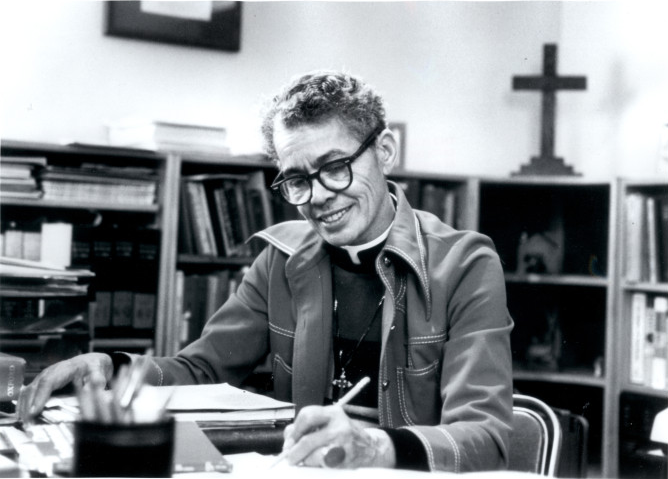

S. Charmaine McKissick-Melton grew up knowing about Pauli Murray. Murray, a civil rights icon, lawyer, writer and Episcopal priest, was born in McKissick-Melton’s hometown of Durham, North Carolina.

But it wasn’t until McKissick-Melton was in college that she really understood the depth of Murray’s impact on America — and the parallels to McKissick-Melton’s own life as a Black woman growing up in the South.

Murray is a renowned author, poet, and priest who paved the way for many African Americans in the United States. Murray wrote “Proud Shoes,” a book about her life growing up. Her legal research was used in the Brown v. Board of Education case, and she is a co-founder of the National Organization for Women.

Like Murray, McKissick-Melton came from a prominent Durham family and was active in the civil rights movement, making history of her own when she and her siblings desegregated all-white schools in the 1950s and ’60s. McKissick-Melton and her brother Floyd Jr. were among the first African American students to attend North Durham Elementary School. Their home, called Freedom House, was a gathering place for civil rights activists from across the country.

McKissick-Melton served as a founding board member of the Pauli Murray Center for History & Social Justice, which is housed in the home where Murray grew up in the West End neighborhood. She stepped down from the board June 30.

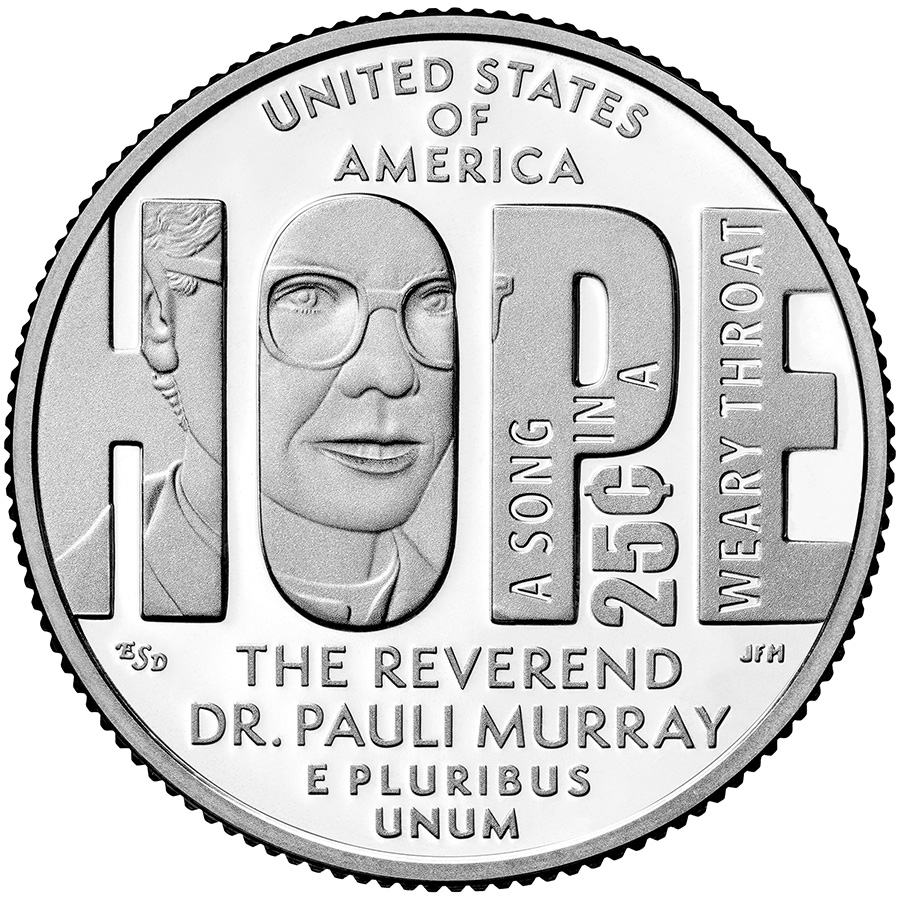

And when Murray was honored with the 11th coin in the U.S. Mint’s American Women Quarters Program, McKissick-Melton was on hand to see the ceremony in Washington, D.C.

“As a Durhamite, born here, I am really proud that I can say, ‘Yes, a Black woman is on the quarter. Her name is Pauli Murray.’ So I bought a whole batch of them from the mint, and I’ve been passing them out,” McKissick-Melton said.

McKissick-Melton earned her undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a master’s degree from Northern Illinois University and a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky. She began her career in broadcasting, working for a decade in radio and television sales and management, before moving to academia. Fondly known as “Dr. Mac,” she taught at Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina, and then North Carolina Central University. She retired in 2022.

At NCCU, she founded what would become the Charmaine McKissick-Melton Communications Fellowship, an internship program through Duke University for NCCU students. In May 2017, she received the UNC Board of Governors Excellence in Teaching Award.

McKissick-Melton spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Julia Zaree French, a 2024 Charmaine McKissick-Melton Communications Fellow, about her involvement in lifting up the legacy of one of the 20th century’s most important human rights activists. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: What was your reaction when you found out there was going to be a quarter honoring Pauli Murray?

S. Charmaine McKissick-Melton: It’s just an honor she really deserves. She’s an amazing person. For a Black woman to be on any coin in the United States of America is truly, truly a statement.

I love the fact that she is on the quarter and that the word is “hope,” with her face inside the O. I actually went to D.C. when the United States Mint honored her for the quarter.

F&L: How did you get involved with the Pauli Murray Center?

SCMM: Barbara Lau, who was head of the Pauli Murray Project before we became a board, reached out to me and said, “Do you know about Pauli?” Since then, three or four people came to me with the concept of “We think you’d be interested — would you consider working with this group?”

Back then, it was just a project, and we were just brainstorming on how we could uplift her name and make sure that people in Durham know who she is. We did lots of different things, like putting placards up in downtown Durham, having book clubs, reading “Proud Shoes,” which is one of the books she wrote particularly about living in the West End of Durham.

I really related to reading “Proud Shoes.” I think I began to love her more, like, “Oh yeah, I can relate to that. I did that too in Durham.”

It was a group of around 20 people: Black women, gay people and City Council members that would come together during lunchtime and brainstorm on what else could be done.

We came up with the concept to become a 501(c)(3) in order to really continue to promote and deal with the house. I later became vice chair of the board and served for about 10 years.

F&L: What does Pauli Murray’s contribution to justice and civil rights mean to you?

SCMM: Pauli brings a whole lot of intersectionality, because she crossed so many barriers in regard to race, sex, gender and identity. This is why we came up with the name Pauli Murray Center for History & Social Justice. We think that embodies the full being of who she was and what she stood for.

She was the first African American female to get an S.J.D., the equivalent to a Ph.D. in law. My father happened to be the first African American to sue and win to go to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, back in 1951. Pauli had actually tried to get into Carolina 10-plus years before my dad.

People thought my dad was crazy. He and three of his friends who were at North Carolina Central University (back then, North Carolina College), a segregated institution, all sued. The case is called McKissick v. Carmichael, and he in fact won in 1951. Even though they were all married and had kids, they all wanted to integrate everything they could over at Carolina.

F&L: Pauli Murray was born in 1910 and died in 1985, so she was from an older generation than you and your parents. Does her story resonate with you?

SCMM: Oh, absolutely. She was just inspirational. She would keep getting turned down for things but just kept trying and just kept trying. Every step along the way, there were people telling her, “No, you can’t do this. Why should you do that?”

I related in the respect that almost every single job I’ve had in life was not designed or meant to be for a woman or a Black person or both. I have plenty of horror tales to tell about being a Black person, a woman, a Black woman or the only Black woman.

I was sales manager for WDUR Foxy Radio — first Black, first woman in this market, to my knowledge. I went with my general manager to the National Association of Broadcasters meeting. When I walked in, they actually turned to him and said, “Is this your girl?” Now, granted, this is decades ago, but still, it was inappropriate then.

I looked at him and thought, “You better say the right answer. ‘Your girl’ — what does that mean?" I assumed they kind of meant like your secretary. They were all white men in the room, and these were sales managers and general managers of radio and TV in the Raleigh-Durham market.

Fortunately, he said, “No, this is my sales manager.” And their mouths literally fell open.

F&L: What’s your advice for the Black women who are the first in their spaces?

SCMM: Have a little patience. I bit my tongue a few times, but I’ll be honest, I used to say this all the time in class at Central: I did what felt right in my soul. I refuse to do things that are unethical or immoral from my personal perspective. And sometimes people don’t like you, but that’s OK as long as I get the respect I deserve. That’s the key.

There are people right now who probably didn’t like me — still don’t like me — and they would not cross me, because they know that I know the law. That’s another thing: know your rights, know your law, know the paperwork, and read the fine print. Knowing the basics is important, so that when you step out there, you’re on solid ground.

I’ve heard this sometimes: “Well, I didn’t get it because I’m Black” or “I didn’t get it because I’m a Black woman.” Well, sometimes you didn’t get it because you aren’t qualified. You are not prepared. I’m just being blunt. You cannot blame it all on that.

Now, it is frequently that too, but you better be sure you have your stuff together before you go claiming that. Do a real self-analysis here. Do I have what it takes for this job? Did I really read that job description again? Did I have all those qualifications? Did I have half of them?

On the other hand, I have sued places because of many problems.

F&L: Your father’s law practice specialized in civil rights litigation, and your family was heavily involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Did you understand at a young age that you were making history?

SCMM: We absolutely knew what we were doing. There’s even a picture that’s now circulated of my brother and me picketing in front of what was Royal Ice Cream, which is now the Durham Union Baptist Church school. I was probably 5 or 6 years old when that photo was taken.

It was an ice cream facility that basically had colored on one side and whites-only on the other side. I talked about it on video for PBS a few years back. We always went as a family to almost all these kinds of functions.

My mother had a station wagon for a while, primarily to keep picket signs in the back of the car, so when we had an occasion or were helping kids, we could stop and picket places that were segregated.

My siblings, in 1959, were not treated well at all. I was only 4 or 5, but I remember my mother would drive my sister to [high] school every day. The kids would hold the door and not let my sister in. Every day, we’d have to get out and park the car and walk to the principal’s office.

She fortunately only had to live with trauma for one year, because the lawsuit did not go through until she was a senior in high school. The only other Black people in that building, other than Larry and Joycelyn, were the cafeteria workers and the janitorial workers. One day, the students cornered Joycelyn and knocked her down a flight of steps. They left her there, unconscious. Fortunately, somebody happened to go down that back staircase, and it happened to be a cafeteria worker, who was actually a [fellow] church member of ours, and they took care of my sister.

My brother and I had some issues also, but because [our classmates] were younger, they just didn’t have as much built-up hostility, so they did not know how to treat us as badly.

F&L: Do you have any advice for the new generation of activists? Is there anything we need to be doing differently?

SCMM: This generation gets it. But we’ve been there, so when we see something happen, we know what’s coming next. We are really frustrated and disappointed right now, because we thought those things we fought for were rights that were in the law that would not change, and it has.

What we did won’t work; it’s just a different world now. I do think that sometimes younger folk blow off the old folks, but a lot of us can offer some valuable insight. We might provide some structural analysis, some strategies that are broad concepts, but we think it’s going to rely upon your generation to figure out.