Today, in post-apartheid South Africa, the church and the seminary have an important role in helping to build and sustain democratic institutions, says Simangaliso Kumalo, the president of Seth Mokitimi Methodist Seminary.

“It is critical that we train our people to participate in developing those institutions and initiatives that enable their liberation and freedom, but also in developing and safeguarding democracy and the rule of law,” Kumalo said.

And that, in turn, shapes the kind of theological education that Seth Mokitimi seminary tries to provide, he said. Even today, South Africa struggles with poverty and injustice.

“We need leaders who are driven by higher ideals to make society function better and help people get those things that they need,” Kumalo said. “So that’s our commitment -- to form leaders who have a passion for developing the church and making sure that the church is relevant and enables people to experience life in its fullness.”

More than any other institution, the church exists for the betterment of others, Kumalo said.

“You are not just preparing people for heaven; you are wanting to make them be able to experience the kingdom of God on earth, where they are,” he said.

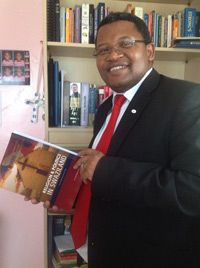

Kumalo has a Ph.D. in theology and development from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. In January, he was inducted as the fourth president of Seth Mokitimi Methodist Seminary, located in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal. An initiative of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa, the school opened in January 2009.

Kumalo was at Duke Divinity School recently and spoke with Faith & Leadership. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: In your acceptance speech at your induction as president of Seth Mokitimi Methodist Seminary, you said your goal for the school was to be an institution that “trains 21st-century leaders, with the dignity of 18th-century Methodism, which trained for social transformation and liberation of the oppressed.” Talk a little bit about that.

Well, Methodism became one of the most influential institutions when it came to South Africa and other African countries. It established institutions -- first the church itself, but also schools that enabled people to develop their lives and become better people. We need to learn from those experiences, especially regarding the kind of leadership that developed institutions that have helped people better their lives.

That’s what I hope we are going to do as we develop these church leaders, especially in an age where people sometimes separate spirituality from real life. We want to build leaders who are going to bring the two together in a synergy that will help transform our society.

Q: Since its founding in 2009, Seth Mokitimi has worked to balance the contextual, the academic and the spiritual in its approach to theological education. How do you do that?

First, we are committed to academic theological reflection. It is important that ministry students understand theology as a discipline, an academic discipline, with an integrity and excellence that is accepted by other theological institutions.

It’s not a second-class kind of academic knowledge. We are committed to training for the church and for people who are going to go and save the church. So we work very closely with the church.

Our students pick up courses that are relevant for ministry. In addition to their academic subjects, they take practical ministerial courses. We also station them in congregations and church-related institutions, including faith-based and faith-inspired organizations, where they can do the theory and practice and learn in the process.

During the weekend, they are also placed in congregations, where they participate. And the seminary itself has a vibrant church community that the students are exposed to.

So that’s what we are trying to do.

Q: What is the role of the church and seminary in developing leaders in a post-apartheid South Africa?

It is critical. It is critical.

During apartheid, our people were not necessarily running the country and were not necessarily responsible for building and sustaining institutions that would facilitate their own development and freedom. All those institutions were there, but they were there because the white government had built them up, and they were serving the interest of that minority population in the country.

Now that you’ve got a democratic government, the people who were not in government before are now running the government. Now they are the ones who are expected to build and sustain these institutions.

So it is critical that we train our people to participate in developing those institutions and initiatives that enable their liberation and freedom, but also in developing and safeguarding democracy and the rule of law. Those are things that people didn’t have to worry about before. Now they do, if the democracy is going to work.

And the church cannot keep distant from those things. It is critical that the church be part of those processes and initiatives that are going to sustain our democracy. Otherwise, if you leave the democracy at the mercy of politicians, you’re losing a contribution that is very, very important that should be made by people of faith.

Q: That’s interesting. There’s a very different conversation in the United States about the church’s role in politics. Talk a little more about that. As a seminary president, what kind of leaders do you hope to form?

The point of departure for us is that we are driven by the understanding that God has a vision of a better world, a better South Africa, even a better Africa than the one we have. It is a vision of life in its fullness, where people’s spiritual needs are met, but also their physical and material needs.

That’s when life is complete and holistic. When any of these is missing, life is not complete. So we want to develop leaders that are going to transform society.

In South Africa, people are struggling so much. Material poverty is rampant. There is violence. There is abuse of women and children. People’s rights are not respected all the time. Justice is not accessed by all people at all times. And as long as you have those situations, then life is not lived in its fullness by people.

So we need leaders who are driven by higher ideals to make society function better and help people get those things that they need. And the church is better-placed to do that.

So that’s our commitment -- to form leaders who have a passion for developing the church and making sure that the church is relevant and enables people to experience life in its fullness.

If you don’t do that, then people separate the church from society. They are concerned just about spiritual needs and developing the church, which is not really complete. People are not just spiritual beings, they’re not just physical beings; they are both. And we need to bring the two worlds together to make things work.

Politics has religion in it; I do not know of any politics anywhere in the world that is free of religion. People claim that they are not religious in politics and that they are secular. But I don’t know anyone that is really secular. Religion itself is political. The two are interdependent; they work with one another.

So we envision a leadership that will find a way of bringing the two together so that there is holistic life for all people.

Q: You are a new leader in a relatively new institution in a time of transition in your country and in your region. How does your school’s approach to education reflect the history of your country, and of theological education in your country?

We are products of liberation theology in many ways, which reminds us that the ultimate goal for humanity is that human beings are free -- they enjoy life, they have justice and equality and dignity, their basic needs are met.

We deal with issues of class and privilege and access to resources, and issues of color, because that’s where we’re coming from.

The education that we are embarking upon makes sure that first, there is access to knowledge by all people. But second, we learn from people’s experiences. We were informed very much by Paulo Freire’s view that education is a process of liberation because it takes into account people’s experiences. You move people from the known to the unknown in education. So education has to be rooted in people’s experiences and their own journey.

In terms of the church, we believe very much that education is a tool through which any member of society can be uplifted and placed into a queue of opportunity where you can reverse the cycle of poverty.

For us, the church is the one unique institution that lives, exists and works for the betterment of others -- more than any other institution. It is the one unique institution that is there to spend itself and be spent for the upliftment of other people in a capitalist world where the emphasis is getting as much as I can for myself. The church doesn’t work from that perspective, and as a result, it is the safe space that can pick up everybody and make a person out of them.

So it is with that perspective that we approach and try to do education. We inculcate in our students the faith that, in their work in the church, you are not just preparing people for heaven; you are wanting to make them be able to experience the kingdom of God on earth, where they are.

Q: At the same time, you’re in a very diverse nation and region, with many religions, cultures, ethnicities and languages. What are the challenges of theological education in that setting?

You are right. It’s a very, very complex society that we live in.

The religions themselves are so diverse. The moment you talk about the church, you are excluding a bigger group that does not adhere to the church. But you can collaborate with those who want to collaborate with you.

There are also different streams of being church. In Africa today, there is much growth in prosperity Christianity, which emphasizes wealth for myself at all costs.

So you then have to bring about a theology that disputes these kinds of toxic theologies that are being taught, theologies that marginalize women or people with different sexual orientations, theologies that emphasize differences and perpetuate ethnic stereotypes and so on.

In my institution, we are continuously challenged to speak about these things -- that our theology is inclusive and embraces people, and promotes rather than denies life, and builds freedom for all people. We emphasize this both in the content and in the methodology that we use in our teaching.

Politically, we bring to the attention of students that the moment they join the ministry and go to college, they join the class of educated people. So they have a responsibility, as part of their faith, to make sure that they educate people about their political rights and the fact that they can improve the political systems through their vote and participation.

In countries where those are nonissues, people can be free without emphasizing them, but we cannot. It is part of the church’s mission to highlight and make people aware of their rights and the significance of those rights in changing their lives and others’.

We are faced with issues of xenophobia, where people are killed and suffering because they come from other countries. That is a very painful experience. So you want to reinforce certain things to the pastors that you produce: What does it mean to be in a country that is xenophobic when you are part of a church that believes that all people are the children of God, created in the image of God? What does it mean to be a church leader in a country where there is so much economic disparity?

Those are issues that we deal with all the time -- in our lectures and during worship, as a worshipping community in the school. That’s how we address those issues. It’s a big challenge, but it is work that needs to be done, and we are doing it.

Q: In your speech at your induction, you said the seminary is open to all and does not discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation or nationality. And you went on to say:

We are committed to teaching men that [you] can be unchauvinistic, Africans that you can subvert the demon of ethnicity, whites that you can be free of the demon of racial superiority, heterosexuals that you can be embracing to people struggling with issues of sexual identity in a homophobic church and society, that you can be your brother or sister’s keeper in a xenophobic country and that you can hold public office without being corrupt.

Do you ever feel that it’s risky, as the seminary’s leader, to speak out so forcefully?

I don’t. I am guided by the fact that there is nothing else that I can say other than that. There’s just no way, because that’s how I understand the seminary to be. If I can’t say these things, then I shouldn’t have picked up the job, you know?

And if this makes it dangerous, that means that I’ve allowed myself to take a dangerous job. This is what I believe in. And as a leader of the seminary and as a Methodist who understands Methodist theology, I expect that when I articulate these things, Methodists will say, “Yes, they’re difficult, but that’s us. You are talking about us when you say this.”

So in that sense, it shouldn’t be dangerous. But I have been made aware by people who have raised the same question. They say to me, “Oh, that was radical, that was prophetic, that was …”

I don’t understand it. Because for me, if I didn’t say this, what else would I have said? This is what summarizes who we are as Methodists. This is what Methodists would like our ministers to believe in.

If one cannot see things this way, then one shouldn’t be picking up this job. Maybe it’s the job that’s dangerous.