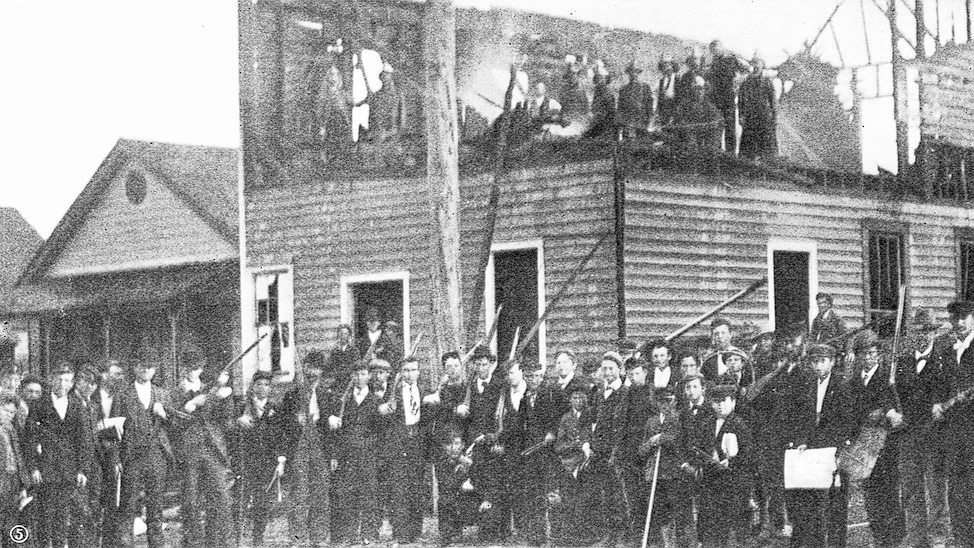

Nov. 10 marks 125 years since the massacre and coup d’etat in Wilmington, North Carolina. The city has never recovered from that unspeakable violence, in which untold numbers of Black residents were murdered or driven away.

At the time, many white Wilmington churches supported racial oppression, and today some of their congregants descend from perpetrators of that tragedy. Wilmington’s traditionally Black churches tried to protect their congregations but were unable to stop the momentum of 1898. Strengthened Jim Crow and disenfranchisement legislation followed, as did decades of lynchings and expulsions within Black communities across the South.

How are we to respond to such a painful history, in Wilmington and in the U.S.? How can we work through the ancestral trauma of racialized violence and injustice rather than unwittingly carrying it into the future?

We both have deep roots in Wilmington, but neither of us learned about 1898 in our youth; the truth wasn’t acknowledged publicly until the mid-1990s. Today, we are members of Wilmington’s chapter of Coming to the Table, a national organization focused on racial healing. During this year’s remembrance week, we have invited church leaders and others from Wilmington’s white and Black communities to a moderated discussion to forge connections and consider how to move forward together.

Here are our stories.

Reggie

Growing up in Wilmington in the 1970s and ’80s was hard. I am the third of five children, and our single mother raised us on government assistance supplemented by work as a domestic. We were food insecure and housing insecure.

I recall the shame of using food stamps at the grocery store, the importance of free lunch at school, and the sad humiliation of my highly intelligent, loving mother being forced to clean other people’s houses, unable to realize her dreams. I remember going surreptitiously to neighbors’ houses after dark to borrow jugs of water for flushing the toilet and cooking, or to heat dinner when our electricity had been shut off.

After years of trying, we finally were allowed to move from the drafty, ultimately condemned house we rented into the Creekwood housing project. Water and electricity were covered by the rent. I was 9, and to me, it felt like the Jeffersons movin’ on up to the East Side.

While my younger self lacked the words or perspective to fully comprehend what was happening around me, I intuitively knew that something was off. Institutional, residential and social forms of segregation were rampant. Opportunity existed along a racial divide, with Black folks mostly on the losing side.

Reflecting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous words that 11 on Sunday morning was the most segregated hour of the week in America, so too were Wilmington’s churches segregated. They largely remain so today. Those we attended were exclusively Black, very poor, and sustained by small but devoted congregations.

Schools remained segregated until the early 1970s in New Hanover County, which bitterly fought integration long after Brown v. Board of Education outlawed “separate but equal” in 1954. They remain largely divided by race today. In fact, Cape Fear Academy — where I received an academic scholarship and became the school’s first Black graduate in 1984 — had been founded as a “segregation academy.” I have written about my experience at CFA; suffice it to say, not everyone was thrilled that I was there.

Long after the end of de jure segregation, there remained places we simply could not go. Even Wilmington’s famed beaches were segregated. For families like mine who didn’t own a car, missing the school bus often meant missing school entirely. As kids, we were sternly warned about areas where it wasn’t safe for Black people, including certain neighborhoods on the way to school. There was always a sense of danger permeating the air.

It all makes sense to me now. The massacre of 1898 explains so much about Wilmington’s current reality: the persistent residential segregation, the lack of meaningful opportunity along racial lines, the hostility, the sense of despair. It’s largely why I became a civil rights lawyer and activist, although I knew nothing about 1898 until relatively recently.

It’s also why I believe that a truth and reconciliation process is essential to healing and transforming this legacy. I dream of someday leading a delegation of 1898 descendants to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama — dedicated to victims of racial terror lynchings in America. Many of those murdered on Nov. 10, 1898, are memorialized there. Such a pilgrimage will be critical to the healing process — of Wilmingtonians and of the city once considered “the jewel of the Cape Fear.”

Lucy

Visiting Wilmington as a child, I would sit with my grandmother at First Presbyterian Church, gazing at the enormous rose window that glowed cobalt and ruby. Even then, I understood that my ancestors had sat in that sanctuary for generations. When I turned 15 and my family moved permanently to Wilmington, I again found myself on many Sundays in those pews.

It wasn’t until I was middle-aged that I learned about the 1898 Wilmington massacre and coup d’etat — and that First Presbyterian’s pastor at that time, the Rev. Peyton Hoge, had been complicit. Like several other Wilmington ministers, Hoge had preached white supremacy. On Nov. 10, 1898, he’d “carried a Winchester on his shoulder during the shootings,” according to David Zucchino’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Wilmington’s Lie.”

And then I learned that my own great-grandfather, William Berry McKoy — who’d taught the Bible at a mission Sunday school — had also been a perpetrator of 1898.

During the centennial remembrance in 1998, First Presbyterian’s choir combined voices with St. Luke’s AME to sing “Let There Be Peace on Earth.” Today, First Presbyterian continues to evolve, promoting racial and gender equity and supporting refugees, including a Congolese family. Some members formed a book club with Black congregants from nearby Chestnut Street Presbyterian to study racism.

Such changes felt deeply encouraging as I considered my own journey of reckoning. After discovering McKoy’s involvement in 1898 — and my family’s history as enslavers — addressing Wilmington’s legacy of injustice became a personal mission. I wondered: What might white people like me owe to people whose ancestors were harmed by our forebears?

Today, I engage in conversations and action planning with descendants of 1898’s victims, promoting racial healing and equity. This has meant unlearning assumptions I absorbed growing up and scrutinizing benefits I enjoyed simply because of skin tone. How didn’t I notice that during those early years at First Presbyterian or in my family’s clubs and social groups, I never saw a single African American? Fish swimming in our singular pale stream, we were utterly oblivious to our privilege.

Sometimes even now, I recognize in myself shocking, ugly detritus of generational racism. I try to remember there’s no way to get it totally “right.” I can only stumble, then step again onto a path toward change.