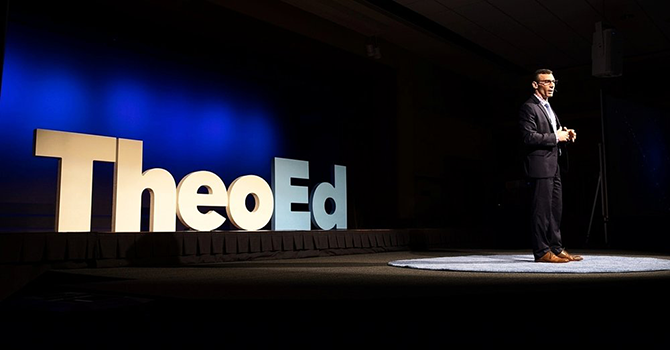

It was an hour before the doors would open. I was beginning to panic. The chairs were set, the sound check was done, and the speakers were ready. All I had left to do was set up the giant TheoEd letters on the stage. The problem was, the lowercase e would not stay in place. It leaned a little to the left, a little to the right, and sometimes it would flop over on its side.

After 18 months of planning and promoting, I thought, this e was about to ruin everything! In truth, it was the least of my concerns.

What I was trying to pull off back in 2017 was risky. At that time, I was a scholar-in-residence at a large church in Atlanta, and I was working with a group of lay leaders to re-imagine the congregation’s annual sermon and lecture series.

We wanted something fresh, something that could reach out into the community. We wanted to make the best learning available in a format that was accessible and engaging to a broader audience.

We wanted to bring a little bit of TED to church.

But could we really pull it off? Would leading thinkers in the church and the academy be willing to give the talk of their lives in 20 minutes or less, as TED Talks do? Would audiences show up? Could we produce the whole thing with the impeccable quality of TED?

We sold out that first TheoEd event, the speakers were fabulous, and the e stayed put.

Since then, we’ve put on seven TheoEd shows, with several thousand in attendance and more than 100,000 viewing our talks online. We have developed discussion guides to go along with each talk and a prize for graduate students. For the first time this February, we took TheoEd on the road, visiting Charlotte, North Carolina.

Through TheoEd, we’ve tried to do for the Bible, theology and spirituality what TED has done for technology, entertainment and design. In the process, we have been learning a lot about what it takes to engage public audiences in conversations about God, religion and the power of faith to shape lives and communities.

Here are three discoveries and how they might help churches and seminaries rethink their approach to education.

Re-imagining the sage on the stage

Conventional wisdom has it that the sage on the stage is dead. At least, that’s what I took away from Parker Palmer’s “The Courage to Teach” when I read it in seminary. Palmer describes a “community of learning” in which the expert is displaced from the center of attention and learning happens through a nonhierarchical web of relations between students, subject and teacher. I love this model and use it in the seminary classes I teach.

Much like Palmer, the TED organizers are convinced that the traditional academic lecture is not an effective vehicle for engaging most audiences. What Palmer solves through decentered, discussion-based learning, TED solves through well-coached speakers, compelling short-format talks, an attractive stage and high-end production.

We’ve followed a similar path in TheoEd. Getting there isn’t easy, as most of our speakers are more comfortable reading lectures from a lectern or delivering sermons from a pulpit. If there’s a secret sauce to TheoEd, it’s the insistence on the highly polished, no-notes, short-talk format that TED popularized.

What TED reminds us is that the church and the seminary of the future will need new wineskins, not just good ideas. We’ll have to let go of some well-established models of education, and we’ll have to lean into creative experiments. Some of those might look like what Palmer describes. Others might, like TED, try to re-imagine the role of the sage and the design of the stage.

Reaching the second audience

What sets TED apart from most speaker series is that its primary audience is not the people who attend in-person conferences. Rather, TED is all about the “second audience” — those who experience its content only digitally. Focusing on the second audience doesn’t just involve remembering to turn on the camera and set up the livestream. From how the speakers are coached to where the cameras are placed, the whole point of TED is to make the second audience feel like the primary audience.

We try to do the same with TheoEd. A case in point: During our February 2020 event, a speaker’s microphone malfunctioned during the first few minutes of the talk. The in-person audience could still hear the speaker, but the malfunction would render the digital recording unusable. Having prepared for this scenario, we paused the talk, fixed the microphone and asked the speaker to start over.

It was a bit awkward for the in-person audience, but we were convinced that this was worth it, because we knew that far more people would eventually listen to this talk through our website than were actually in the room that day.

If churches and seminaries are going to get serious about using digital media to reach new audiences, they will have to start designing offerings with the second audience squarely in mind.

How will that change things? It will mean paying more attention to elements like lighting, sound quality, camera angles, stage design and run of show. It will also mean making strategic decisions about which offerings should be online and which should not — doing less might well be the key to doing better when it comes to reaching the second audience.

Creating communities of curious souls

The look and feel of TED is inviting and inquisitive. The talks prompt the audience to ask questions and to consider new ideas — or to revisit old ones. The point of TED, as its website says, is to create “a community of curious souls.”

Isn’t that what a church should be — a community of curious souls? Becoming such a community will mean valuing questions over creeds, dialogue over dogmatism (whether conservative or liberal) and wrestling with difficult texts over trying to protect God from people’s doubts.

It will also mean rethinking where education happens. We’ve chosen to hold TheoEd in community centers and performance venues rather than church sanctuaries. We’ve found that these spaces can be more inviting to those for whom the institutional church has ceased to be a place of meaningful belonging.

Rather than inviting people to their buildings, perhaps it’s time for churches and seminaries to do their work out where their audiences are already gathering — coffee shops, pubs, community centers, art venues, gyms, parks.

Taking TED to church is no panacea for all that ails traditional models of Christian learning and theological education. But learning from TED is, as their tagline puts it, an idea worth spreading.

What TED reminds us is that the church and the seminary of the future will need new wineskins, not just good ideas.