Nine-year-old Caleb Barnett of Edina, Minnesota, wasn’t the only one getting a bit teary in May when he reluctantly reached for his 2020 calendar and crossed off Christian camp, cancelled because of the coronavirus pandemic. His mother, Sarah, was as sad as he was. She runs camps for the Episcopal Church in Minnesota (ECMN) and knew he’d be missing a fun learning experience.

But she began to see raw material for Caleb’s ongoing spiritual formation in the community that started showing up on their doorstep. Every day at noon, a group of his bike-riding friends -- no longer tightly scheduled with organized activities -- would swing by to get him and cruise the neighborhood.

Having gotten to know their parents, she decided to invite the families over every Friday for a socially distant backyard camp that’s largely about Christian hospitality -- and they’ve been coming. There are even matching T-shirts for all the kids.

“I’ve actually thought of that as how I could empower my camp families to be that kind of local presence in their neighborhoods this summer,” said Barnett, the missioner for children, youth, camp and young adults with ECMN. “Maybe they just do a little picnic every Friday, invite their kids’ friends’ families and do this kind of relational ministry that Jesus was all about, even if it’s not vacation Bible school format.”

As the strange summer of 2020 arrives, families are finding that they can’t count on the usual seasonal programming to help kids keep making progress in spiritual formation. Short-term mission trips are canceled. Christian camps and vacation Bible schools are taking the season off or pivoting temporarily to new models that can be administered at home, in small, socially distanced groups or online.

That means parents can’t rely solely on professionals to move the faith formation process along. Indeed, those professionals are doubling down on their roles as supporters and partners of family-based ministries. They’re becoming equippers by innovating from within their formation traditions -- first by assessing families’ needs, then by adapting what they have to offer. Formation experts say it’s a sound approach: experimenting -- fully expecting failures -- and frequently reassessing.

What might your congregation learn with a license to experiment?

“Because we’re designing something new, all bets are off. We’re not dealing with sacred cows right now,” said Abigail Visco Rusert, the director of the Institute for Youth Ministry at Princeton Theological Seminary. “In some ways, it’s a clean slate for this summer. There are so many restrictions, so many hurdles -- but that’s where the opportunity lies, too.”

Parents consider the options

Many parents feel torn. Sacred Playgrounds, a consultancy that conducted an April survey of about 2,500 parents who’d previously sent kids to mostly mainline Protestant camps, found that only 19% said they would send their kids to virtual camp programs this year. Another 41% said maybe; 40% said no, not even if it’s free.

Parents who have already been looking beyond traditional programming for their kids find this summer nudging them further toward alternatives. A decade ago, Adrienne Davis of Durham, North Carolina, was a big believer in short-term mission trips and VBS, but now she and her husband use a broader array of tools for shaping their three elementary-age children.

“We really started interrogating, Are those [types of programs] the only ways that our kids are growing spiritually?” said Davis, who grew up in an African Methodist Episcopal church and now attends a United Methodist congregation with her family.

In what ways do you see children and youth growing spiritually outside your church’s traditional programming?

They also began to question, she said, whether long-distance mission trips are necessary when so many needs exist near home. She said they aim to foster an environment where their kids learn to confront racism, to integrate faith into daily life and to express whatever doubts they might have.

In past years, the Davis kids have attended a nonreligious anti-racism day camp that’s run by Christians whose values the Davises share. This year, they’ll be doing safe outdoor activities such as hiking among peers and adults who speak a language of faith.

“Just being in nature, being reconnected to people and land in particular, is kind of our focus right now as we’re trying to keep our kids sane,” said Davis, whose children are 6, 8 and 11.

Other parents are interested in giving virtual camp a try. For Kari Duong-Topp of Apple Valley, Minnesota, camps offered through the Episcopal Church in Minnesota have given her two children exposure to a cross section of youth. She hopes that her son, now 17, will say yes to ECMN’s alternative this year: weekly Zoom gatherings with his cabin mates from last year, interspersed with activities designed to be fun and reinforce faith commitments.

He’s resisted attending church since he was in fifth or sixth grade, Duong-Topp said. But camp was a different story: “Camp gave him a place to talk about some of these things and hear other people talking about it and learn about being of service in a way that he tolerated,” she said.

Formation as a process, not an end product

Pandemic restrictions have already forced local churches to cancel activities and rethink possibilities. At Paoli Presbyterian Church in Paoli, Pennsylvania, for example, adult leaders discerned that spreading joy in anxious times was a congregational need.

They assembled a youth advisory team that came up with challenges open to everyone in the church, such as chalking sidewalks with joyful words or filling bins with items for 13 graduating seniors. These efforts became known as The Joy Project and drew wide, enthusiastic participation.

“The reason it’s youth formation is that The Joy Project was led by young people and really did seem to engage young people,” said Paoli Presbyterian co-Pastor Becca Bruner. “When the young people come up with the ideas and say, ‘Yeah, that’s something I’d like to do,’ everybody jumps on board.”

When pursuing formation goals, such as youth leadership in ministry, one helpful practice is human-centered design thinking, said Rusert, of Princeton’s Institute for Youth Ministry. A concept borrowed from engineering, it begins with consideration of an end user’s needs and context, then works backward to develop systems that are continually tested for user friendliness.

In youth ministry, it can involve identifying core constituencies, naming perceived needs and being willing to keep trying even if initial attempts don’t deliver on a specific result, such as increasing biblical literacy among youth over the summer.

In what ways is your church seeking to unearth what God is doing in the lives of your young people?

Formation is ongoing, Rusert said, never finished in youth or adults. For youth, it is a process of “unearthing” what God is already doing in their lives, rather than trying to mold them into an ideal “product,” she said.

They’re most affected when this unearthing ministry, which makes youth more aware of who they are and where they feel called, flows from loved ones close to them, such as parents and guardians.

“The thing that has been most successful for the churches that we’ve worked with is when they’ve integrated young people on the front end,” Rusert said. “It has made all the difference to those young people feeling fed along the way.”

What kinds of faith lessons can be learned living with the constraints of a pandemic?

Formation happens in part by living out the faith’s lessons in real-life situations, according to Christian camp consultant Jacob Sorenson of Sacred Playgrounds. In his view, nothing can substitute for a physical camp setting where kids are away from home, differentiating what they believe as individuals and navigating life together.

If a child leaves clothes on someone’s bed, for example, and that person is annoyed, “there has to be some sort of reconciliation and forgiveness,” Sorenson said.

“So it’s not just learning about these things as a disembodied concept. … No, it’s like, ‘I have been forgiven. I ticked somebody off. I hurt somebody’s feelings when I didn’t mean to. I have been forgiven for it, and we now move forward as a community, because that’s what we do at camp.’”

This year, none of that seems likely, at least in a conventional form, as summer begins. Though some states haven’t ruled out mid- or late-summer camps for limited numbers, it’s not clear whether that will happen. For instance, as of June 9, at least 81 of the 119 sites affiliated with Lutheran Outdoor Ministries had decided not to open for traditional camp.

Rethinking VBS

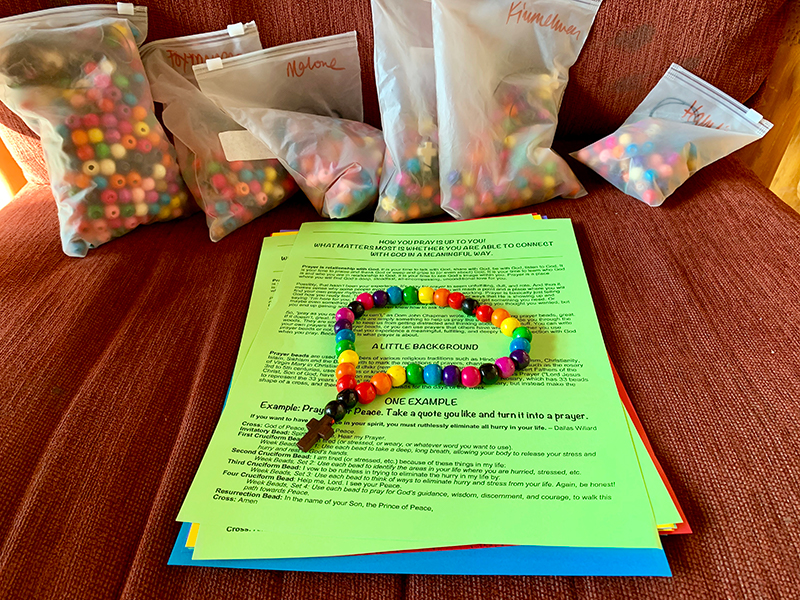

Vacation Bible school is getting a remake in terms of format this year, though reconfigurations vary in approach. In Johns Creek, Georgia, families are used to dropping kids off at Johns Creek Presbyterian Church for a four-day program that costs $40 for the week. This year, they’ll pay a suggested donation of just $10 for supplies that they’ll pick up, but they won’t be on their own, according to Allison Shearouse, the church’s director of Christian education.

VBS ambassadors, who might normally have led stations at the church during VBS, instead might organize two or three families to do some of the activities together.

“This is allowing us the opportunity to do VBS in a way that makes it more a part of their community and day-to-day life than maybe it had been in the past,” Shearouse said.

At Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., VBS organizers are taking a different approach. Vacation Bible school will still meet nightly for a week as usual, but instead of three hours at the church, this year’s program will be condensed into one hour per night by Zoom.

“Keep it engaging, keep it short, and don’t overwhelm our people” is the approach, said the Rev. Thomas Brackeen, the minister to youth and families at Metropolitan AME. “We can extend our outreach beyond the church walls by providing these virtual opportunities.”

How can your church use online opportunities to reinforce relationships rather than replace programming?

The online mode suits Metropolitan, Brackeen said, because it’s a commuter congregation. Most members live outside the city; many drive as far as 45 minutes each way. Unlike for Johns Creek, clustering in backyards for VBS activities won’t work for Metropolitan’s dispersed congregation. Yet the more frequently kids hop online to join friends and adults from church, the more they feel connected despite geographic distances. VBS will reinforce that habit this year.

“We are focusing on, 'How can we leverage this technology so that we can make this a staple of what we do?'” Brackeen said.

What can be better this year?

Camps are crafting their approaches to take advantage of what they still have at their disposal, ranging from facilities to networks of ministry partners. The tailoring varies according to what’s needed, what’s valued and what’s doable.

At Flathead Lutheran Bible Camp on a lake near Kalispell, Montana, families and other small groups will be able to visit this summer, stay in cabins and get a modified taste of camp. They’ll stay with their own cohorts, such as a family or other small group, so as to mitigate public health risks. They’ll eat in a dining hall where capacity will be capped at 50, rather than the usual 300. Each group will have a camp staffer assigned to facilitate activities both physical and spiritual, such as morning archery or time on the ropes course, followed by an afternoon Bible study.

“We’ll still be offering program, just on a more individualized basis,” said Executive Director Margie Fiedler. “So many families that we talk to don’t have a lot of faith development in their home. We’re bringing this as a start to that, where they feel comfortable doing family devotions or it becomes a pattern for them.”

At Luther Crest Bible Camp in Alexandria, Minnesota, the approach is more of a hybrid, with an emphasis on virtual ministry in hopes of growing the camp’s reach beyond its relatively small physical site. Families may rent cabins and have staffers lead them in activities, but much of this year’s preparation has gone toward building an online camp experience called Bold Transformational Faith.

One day a week for the month of July, kids will come together on Zoom for live worship, community building and Bible study sessions in age-based “cabin” groups, and other camp activities. The evenings will have options for Bible studies tailored to families.

“What we know people will come away with is a way of seeing where the Holy Spirit is moving in their day-to-day lives,” said Maddie Elliott, the camp’s associate director. “We want people to walk away saying, ‘These are questions I can ask every day.’”

The virtual camp approach is not without critics. While Luther Crest Executive Director David Holtz envisions a virtual camp option enduring after the pandemic ends, Sorenson, who conducted the Sacred Playgrounds survey of parents, cautions against normalizing a pathway that doesn’t bring kids together in person for unplugged activities.

“Camp is a place to unplug from home, … to develop independence, to think through your own faith, and also to unplug literally from devices,” Sorenson said. “What’s happening with virtual camp is the exact opposite of what we are trying to do at camp.”

Limitations notwithstanding, some churches are giving virtual formation a try this year. Five congregations have signed up for virtual mission trips with Incredible Days, a mission trip planning agency offering virtual experiences this year. One incentive is the cost. For $300, a group of middle schoolers from Bloomfield Congregational Church in Connecticut can have a virtual weekend exploring Los Angeles, versus the $1200 that they’d budgeted for an actual weekend in Boston.

“The kids are pretty burned out from school online,” and need a break, said Dorine DeCarli, the director of Christian education at Bloomfield Congregational, a United Church of Christ congregation. “But I still truly believe they can get something from [the virtual trip]. It still gets them together and gives them a taste of what’s out there in the world, rather than in their own little world.”

Instead of packing duffle bags for a bus ride this June, the kids were getting ready for Zoom meetings with Los Angeles neighborhood advocates, Google Earth tours and online games.

It wouldn’t make up for the face-to-face encounters they had planned to have at a Boston food ministry and domestic violence shelter. But it might help fill gaps in a child’s formation that would normally be neglected in conventional programming, according to Andrew Wicks of Incredible Days. At least that’s the hope.

“It doesn’t matter how many meals we serve … if we’re not dealing with bigger systemic change to deal with urban poverty,” Wicks said. “But when you’re online with remote access to digital tools, it is so much easier.”

How can your congregation use this season to educate one another about larger systemic issues facing your community?

Participants on one virtual trip this summer will videoconference with a denominational lobbyist, state lawmakers and a community organizer from the local area they’re virtually visiting. That wouldn’t be possible, Wicks said, if each meeting required sitting down in person. And the kids will learn how to advocate online about issues in the future.

As families face the challenge of bringing youth spiritual formation literally in-house this year, experts say they should be confident that they’re up to the task -- perhaps to a greater degree than they realize. And they’ve got a license to experiment -- even to fail sometimes -- because the terrain is unknown to everyone.

In the absence of familiar vehicles like camp, experimentation has a chance to flourish this summer, Rusert said, with formation programs shifting to new roles as supporting cast for intergenerational outreach.

“We have a whole summer of not having camp to go ahead and try things out,” she said.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- What might your congregation learn with a license to experiment?

- In what ways do you see children and youth growing spiritually outside your church’s traditional programming?

- In what ways is your church seeking to unearth what God is doing in the lives of your young people?

- What kinds of faith lessons can be learned living with the constraints of a pandemic?

- How can your church use online opportunities to reinforce relationships rather than replace programming?

- How can your congregation use this season to educate one another about larger systemic issues facing your community?