If the white man has inflicted the wound of racism upon black men, the cost has been that he would receive the mirror image of that wound into himself. … The wound is there, and it is a profound disorder.

— Wendell Berry, “The Hidden Wound”

The glorification of one race and the consequent debasement of another — or others —always has been and always will be a recipe for murder. … Whoever debases others is debasing himself.

— James Baldwin, “The Fire Next Time”

I have been a pastor for 43 years in predominantly white churches. That means that I have been complicit in maintaining a religious system that has, often outside our awareness, demeaned, disrespected and harmed our Black neighbors.

It has taken me years to claim this understanding of myself; but now at age 78, it’s time to make a clear statement about my learnings and my identity.

In the 1960s and ’70s, we white, progressive clergy thought we knew exactly what to do — sign the anti-segregation petitions, write letters to the editor, take clear stands from the pulpit, go to marches in the street. Most all of these actions were “out there” — in the public square, the house of worship, the pastor’s witness.

But following George Floyd’s knee-on-the-neck murder by a white police officer, the time of reckoning emerged for me — and the white faith community of which I’m a part. I needed new ways to engage in the struggle.

I know now that I am a racist, complicit in a racist system, which includes all our institutions: education, housing, health care, employment, criminal-legal and the church.

What do I do about it?

As I consider new ways to engage in anti-racism work, I’ve made some commitments based on what I’ve learned. They include taking the time to develop relationships across the lines of race and class, finding ways to move white money into Black-led justice initiatives, and intentional self-examination.

I believe that God needs white people to work for justice (Micah 6:8). As Cornel West put it, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” And justice can emerge from relationships.

So I will be intentional in developing relationships, taking the time to establish trusting friendships with Black colleagues and friends. It does take time — something that can be hard to accept when you are on fire to change the world.

My church worked in Walltown, a historic, predominantly Black Durham neighborhood with a rich civil rights history facing the issues that arise from high rates of poverty and crime. Five pastors — three Black and two white — met together monthly for three years before launching a joint ministry in 1999.

I was the one who kept insisting that we need to “do something together.” One of my Black colleagues, the Rev. Robert Daniels of St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church in Walltown, would say, “It’s not time yet, Mel.”

I learned during this process that once we have genuine, trusting relationships with our Black neighbors, we are beginning the work of overcoming racism. We are human beings together. We belong together. We are members of the same human family. But it takes time in a broken world to earn that trust.

Racism is the root cause of poverty. My Black friends keep teaching me this truth. My job now is to follow the leadership of those who live the struggle, because racial justice is inextricably linked to economic justice.

Aided by our privilege, many of us white folks have accumulated more money than we need. As part of my anti-racism commitment, I have resolved to encourage a “ministry of liberation” — liberating individuals, foundations, endowments and churches from their money.

What about contributing a portion of all endowments and savings? Let’s start with the biblical 10%, then move to 40%, disbursing those funds to Black-led initiatives — to support businesses, home ownership and education.

At the beginning of the 2020 pandemic, a coalition of five of our Durham organizations came together to develop a local “transformative strategy.” Our Black friends led the way in proposing that we establish a Thriving Communities Fund, with a goal of raising $100,000 to distribute in grants to Black-led businesses that did not receive federal funding. The fund was housed in a nonprofit led by Black women, Communities in Partnership.

Within eight months, we had raised $120,000. This is one example of a local equity-enhancing strategy, Black-led, that aims to reduce the racial wealth gap.

Likewise, I have pledged half of my retirement fund to go, upon my death, to Black-led justice initiatives. My two adult children have agreed to make the decisions about specific initiatives that will receive funding.

At the local level, we need to be involved in repairing the harm, making restitution for the racial and economic injustices perpetrated on our Black neighbors. We can do this through developing specific equity-enhancing transformative strategies that help reduce the racial wealth gap.

But what about inner conversion? How can we move from our heads to our hearts? I found it enormously helpful to be a part of a Confronting Whiteness group, led by the Rev. Ben Boswell of Myers Park Baptist Church in Charlotte, North Carolina. This group focused on reading Black writers such as James Baldwin and bell hooks and watching films by Black filmmakers.

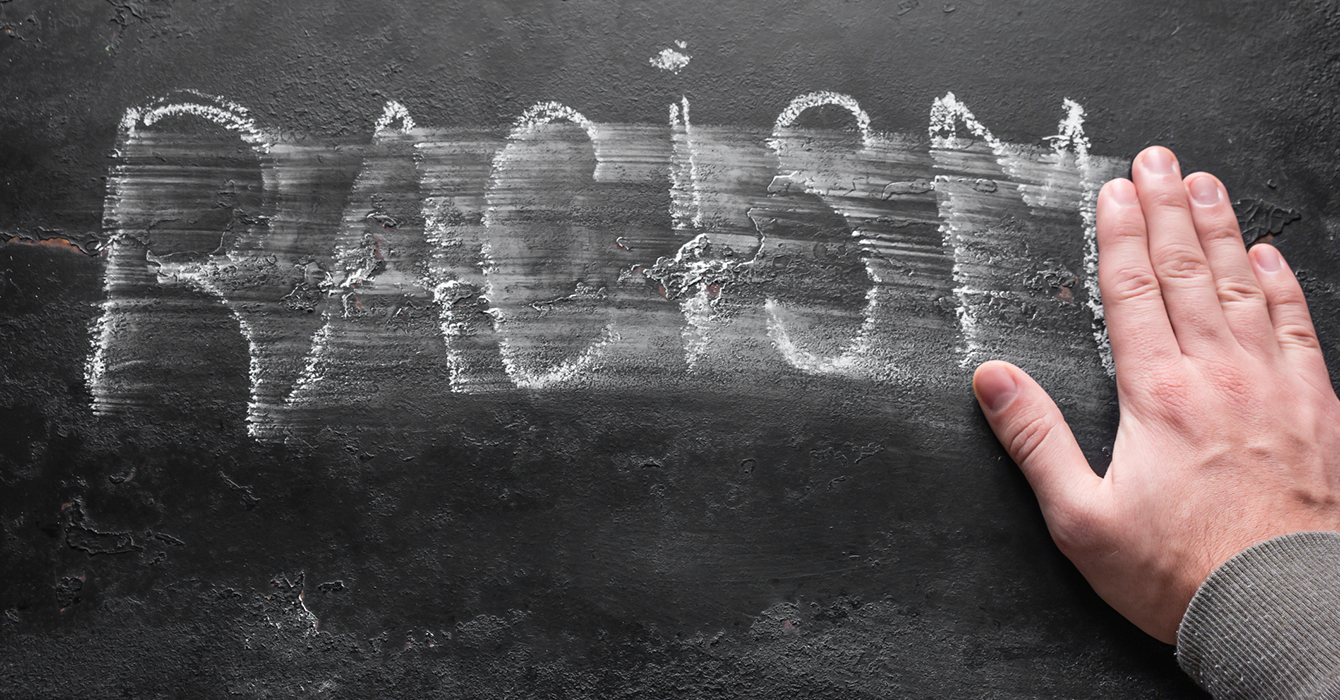

The group led me into a visceral experience — a descent into the heart — of my own whiteness and the harm that whiteness has caused. This experience has led me to see that we white people carry an inner disorder, an intergenerational illness — the “wound” that Wendell Berry writes about.

As our Black brother the Rev. Dr. James A. Forbes once asked a group of whites, “How does it feel to be bound in the clutches of racism?”

Through the years of my pulpit ministry, I have heard myself say repeatedly to my worshipping congregation, “Pick up the near edge of some great problem and act at some cost to yourself.” I am trying to practice what I preach.

We belong together — boundless belonging. I believe that there are steps we white people can take that release new energy and create new opportunities to repair the harm, to make restitution and to heal the wound of racism. And that can move us all toward a more just and fair beloved community.