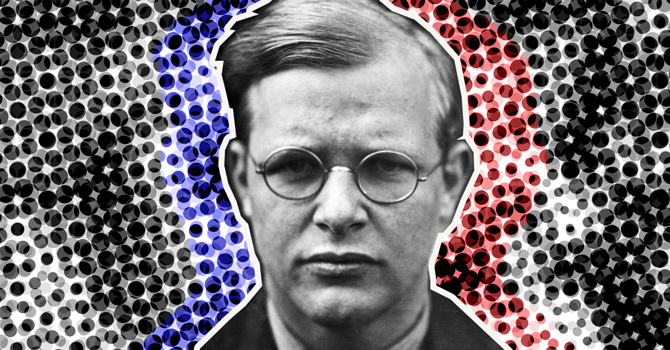

Would Dietrich Bonhoeffer vote for President Donald Trump or oppose him? Were he alive today, would he align with conservatives or liberals, evangelicals or mainliners? What is his legacy for contemporary Christians who would follow his teachings?

Bonhoeffer, who was 39 when he was hanged by the Nazis for his opposition to the regime, remains a compelling figure. Though his theological project was unfinished at the time of his death -- or perhaps in part because of this -- he continues to be taught and debated more than 70 years later.

Faith & Leadership invited five scholars to reflect on the legacy of Bonhoeffer and the relevance of his thought for American Christians. Here are their reflections on the question, Why is Dietrich Bonhoeffer relevant today?

The Bonhoeffer dilemma

By Stephen R. Haynes

By Stephen R. Haynes

Author of “The Battle for Bonhoeffer: Debating Discipleship in the Age of Trump”

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed that appeared a few weeks before the November 2016 presidential election, Eric Metaxas, best known for writing “Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy,” implored Christians to vote for Donald Trump.

He reasoned that support for Trump was incumbent upon Christians because, despite a recently released audiotape of the candidate making “horrifying” comments, the electoral alternative was simply unthinkable. As guidance for navigating these “strange times,” Metaxas compared Trump’s “odious” behavior to Bonhoeffer’s own willingness to do “things most Christians of his day were disgusted by.”

Bonhoeffer scholars like me were stunned that anyone -- let alone someone widely regarded as an authority on Bonhoeffer’s life -- would compare Trump to the author of “Discipleship.”

This was not because, as Metaxas would have it, we are a collection of liberals, radicals and death-of-God-ers who have abandoned orthodox Christianity; rather, it was because we have spent decades studying Bonhoeffer with particular attention to the ecclesiastical failures that made it necessary for him to oppose Hitler by radical means.

I responded to Metaxas after the election with a Bonhoeffer-themed call to resistance in The Huffington Post that eventually became my book “The Battle for Bonhoeffer: Debating Discipleship in the Age of Trump.” In a postscript called “An Open Letter to Christians Who Love Bonhoeffer but (Still) Support Trump,” I pleaded with evangelical Christians to recognize that their enthusiasm for the president was reminiscent of the church’s capitulation to Hitler in the 1930s.

I continue to believe that American Christians’ uncritical support for an ethnonationalist and would-be autocrat lies at the heart of Bonhoeffer’s relevance today. Bonhoeffer became the “Bonhoeffer” we celebrate because he concluded that he must step outside the mainstream of Christian opinion and resist Hitler alongside principled and patriotic military men, civil servants and intellectuals.

As the impeachment inquiry plays out, it feels as though American evangelicals are presenting the rest of us with a similar choice: be carried along by a wave of religiously sanctioned nationalism and hostility to “outsiders” or join forces with principled and patriotic men and women who are determined to resist an existential threat to our democracy.

At some point in the future, we may have the leisure to carefully assess how it happened that millions of American Christians came to understand themselves as lovers of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and avid supporters of Donald Trump.

For the moment, however, we seem to be caught in a dilemma that is eerily similar to the one Bonhoeffer faced: the untenable stance that our country’s preservation depends on the triumph of co-religionists who believe that our leader has been “chosen by God” or the difficult counterstance that it depends on the moral courage of politicians and civil servants with an abiding and sacrificial faith in American traditions and institutions.

Life guided by imagined ideals is a denial of the incarnation

By Reggie L. Williams

By Reggie L. Williams

Author of “Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance”

I encourage students of Dietrich Bonhoeffer to engage his work by way of analogy. To do that, they have to know the many ways that his context was both different from and similar to our own.

One major point of connection to his time is the political climate. During his era, it was animated by fantasies that are still very much with us. While manifested in various ways, those fantasies focus on some hoped-for idealized community.

Such fantasies resemble lethal pathogens. They are hegemonic -- in favor of some, against others, yet eventually harmful to everyone. They prohibit society from experiencing the life that we are meant to live together.

That is where we are today -- dealing with ideological pathogens that have been given a platform by the holder of the nation’s highest political office, fueling harmful fantasies of an idyllic national past.

Bonhoeffer was killed because he was a traitor to Hitler’s government, which was lusting for a society populated with people just like him. Bonhoeffer fit their imagined template of the pure German -- the Aryan. To them, he was the apotheosis of the human, the ideal human for the ideal community.

And for Bonhoeffer, that was precisely the problem. Life guided by imagined ideals renders us incapable of engaging life with real neighbors in the real world. The failure to engage life is a denial of the incarnation. Life lived in that way does not allow for the demands that embodied people make of us by their presence; we become faithful only in our imagination. By contrast, life lived through Christ compels us to love our neighbor in the concreteness of embodied interaction.

It is in that dichotomy, between the imagined and the real, where Bonhoeffer remains relevant for us today.

In our contexts, the very notion of human is overdetermined by baggage that disallows engagement with real life. The history of citizenship in the United States illustrates this point.

Citizenship is enmeshed with an ideology of human difference that equates white with human and citizen. The 1857 Dred Scott decision defined U.S. citizenship and its corresponding civil rights as goods for whites only. The 14th and 15th amendments were meant to correct the violence of Dred Scott and grant citizenship with rights to black people. But it wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that the nation was forced to legally confront this violent past.

Still, laws can’t defeat poisonous ideologies. We remain encumbered by the baggage that binds the notion of human being to white citizen. Our convictions about the way the world works are fixed within the way we see the world.

Bonhoeffer’s theology is embedded within a historical moment when most Germans were devoted to a fantasy of an ideal community. And although the year is different, we find ourselves in such a moment. It’s as important for Christians today to favor real, embodied life.

Bonhoeffer argued that we must make embodied encounter -- not “wish-dreams” of community -- the point of departure for discerning faithfulness to Christ, who said, “I am … life.”

To do that, we must simultaneously do the work of destroying toxic ideological pathogens that prohibit our ability to fulfill the commandment to love our neighbor as ourselves.

I imagine a world in which we recognize the face of Christ in others

By Lori Brandt Hale

By Lori Brandt Hale

Co-editor of and contributor to the forthcoming book “The Political Theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer”

Bonhoeffer is relevant today because he encourages us to see “the great events of world history from below,” to see the world “from the perspective of the outcasts, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed and reviled, in short from the perspective of the suffering” -- as he wrote in “Letters and Papers from Prison.”

I am both moved and guided by these theological and ethical insights. And these insights, shaped and compelled by the injustice and violence of Bonhoeffer’s political and historical context, can help us today in the midst of our own political and social turmoil.

More specifically, I return again and again to three ideas in Bonhoeffer’s work. First, Bonhoeffer says that when I encounter an “other,” that “other” places an ethical demand on me. Second, he links discipleship and vicarious representative action, which he calls in German “Stellvertretung.” Lastly, Bonhoeffer asks who Christ is for us today.

I would like to examine these ideas and imagine the ways in which each might shape our world today.

To the first point: in Bonhoeffer’s earliest work, his dissertation “Sanctorum Communio: A Theological Study of the Sociology of the Church,” he argues that a “person exists always and only in ethical responsibility … vis-à-vis an ‘other.’”

This is a foundational idea, tied inextricably to his Christology, that serves as the hermeneutical key for understanding his ideas about Christian discipleship and political resistance.

I imagine political policies shaped by considering the needs of others as our responsibility.

To the second point: Bonhoeffer’s famous book “Discipleship” explores, in the words of the English edition’s editors, “the problem of following Christ at a time when so many were in thrall to a seductive earthly lord.”

But following after Christ, in Bonhoeffer’s estimation, is straightforward. It requires two things: faith and obedience. And it is grounded on Bonhoeffer’s understanding that Jesus Christ acted vicariously on behalf of humanity, an idea Bonhoeffer introduced in theological terms in his dissertation and developed in ethical terms in his work “Ethics.”

I imagine the ways our communities would benefit if those with power and privilege acted on behalf of those without either.

To the third point: Bonhoeffer does not proclaim an abstract ethic, good for all times and places. Rather, he advances a concrete ethic in accordance with the humanity of Christ.

“Christ was not concerned about whether ‘the maxim of an action’ could become ‘a principle of universal law,’ but whether my action now helps my neighbor,” he wrote in “Ethics.” Bonhoeffer was concerned about “how Christ may take form among us today and here.”

I imagine all Christians recognizing Christ in the faces of immigrants and Muslims and transgender youth.

Bonhoeffer’s life, and death, remind me that I can do more than just imagine these things. I can work for a world in which all Christians recognize Christ in the faces of all others and act accordingly.

Bonhoeffer’s Christian humanism -- a theology forged in the crucible of modernity

By Jens Zimmermann

By Jens Zimmermann

Author of “Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Christian Humanism”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s relevance today seems obvious. Politicians of all stripes praise him as a Nazi resister, champion of human justice and defender of human rights. He also enjoys great popularity as a devotional writer, sanctified by his martyrdom at the hand of Hitler’s executioners.

And yet for anyone who cares to dig a little deeper, Bonhoeffer’s actual relevance lies elsewhere. The reason he remains one of the most studied modern theologians is his Christian humanism.

By Christian humanism I mean the overall character of his theology, a theology certainly tested by Nazi politics, but more importantly, a theology forged in the crucible of modernity, shaped by the intellectual climate that still influences us today.

Bonhoeffer wrote at a time when philosophers criticized the facile positivism of science and when many had become disenchanted with the traditional pieties of religion. He thought about God and reality at the beginning of what we now call postmodernity and wondered how God still speaks to us in a largely secular age.

Bonhoeffer’s answer to this question was the incarnation. His theology is a Christian humanism because it centers on God’s becoming a human being and entering into creation in order to restore it. Among the many consequences of this theological outlook, two especially ensure Bonhoeffer’s relevance for our current intellectual climate.

First, because God became human in order to save creation, Bonhoeffer affirms the importance of the body, creation care and human rights. He claimed that we exist only as bodies. “To live as a human being,” he wrote in “Creation and Fall,” “means to live as a body in the spirit. Flight from the body is as much flight from being human as is flight from the spirit.”

For Bonhoeffer, the body was part of God’s image in us, tying us in responsibility to the earth and to one another. “For in their bodily nature human beings are related to the earth and to other bodies; they are there for others and are dependent upon others. In their bodily existence human beings find their brothers and sisters and find the earth,” he wrote in “Creation and Fall.”

Not only did he insist on our care for creation, but he was also the first Protestant of his time to promulgate natural human rights based on the right to bodily life.

Second, Bonhoeffer developed what we now call an interpretive or hermeneutic view of revelation. Our knowledge about God, he believed, has to follow the pattern of the incarnation itself, in which God reveals his truth via a concrete person within a certain historical context of language and culture.

Consequently, God’s will has to be discerned within the human domain. As Bonhoeffer put it in his “Ethics,” “Just as the reality of God has entered the reality of the world in Christ, what is Christian cannot be had otherwise than in what is worldly, the ‘supernatural’ only in the natural, the holy only in the profane, the revelational only in the rational.”

Truth, we’d say today, requires interpretation.

The Christian life, Bonhoeffer concluded, is all about becoming truly human, by living faithfully by discerning God’s will, caring for creation and one another. That’s what it means to become like Christ, God’s exemplar of true humanity. And it is this Christian humanism that makes Bonhoeffer relevant today.

A church that loves the world more than the world loves itself: Bonhoeffer’s question and ours

By Robert C. Saler

By Robert C. Saler

Teaches courses on Bonhoeffer at Christian Theological Seminary

Dietrich Bonhoeffer saw two pieces of a vision: a church that is deeply invested in its own practices and a church that forms disciples to be more worldly than the world -- to be as deep in the world as God is, in Christ.

He never reconciled those two pieces of his vision; it is left to us to do that work.

Today the church needs to be a community whose actions take on less the character of public religion and more the quiet disciplines of worship and genuine community that form disciples of Christ apart from institutional respectability.

The church should break free of its role as underwriter of social “ethics” and enter into the world’s brokenness in weakness and in service. Bonhoeffer’s life and theology give us a hint of what that looks like.

One of the most pathos-laden aspects of Bonhoeffer’s theology is that while he was one of the most pro-church theologians of the 20th century, in a very real sense he was ecclesially homeless.

Having grown up in a household that rarely attended church, he experienced in only brief glimpses -- in Rome, Abyssinian Baptist Church, the illegal seminary at Finkenwalde -- the embodied community of faith he described in “Discipleship” and “Life Together.” Indeed, for the most part, he experienced the church as a failure.

Not only was the German church united under Nazification, but even the Confessing Church movement, of which Bonhoeffer was an early and enthusiastic supporter, eventually disintegrated once the Nazis granted some basic concessions.

This led him to argue for what he would call “this-worldly,” or “religionless,” Christianity in which the Christian would be fully invested in the world and its brokenness without recourse to the distance characteristic of “religion.”

In Bonhoeffer’s early and midcareer works, he was interested in how discipleship in Christ establishes the church as a community set apart within the world for the sake of the world, one in which the call to obedience in Christ provides an apocalyptic counterpoint to the denatured Christian ethics of classical liberalism.

But he later became fascinated with what it would mean for the path of discipleship to engage a “world come of age” by becoming more worldly, precisely because this is what the God of weakness chooses to do in the incarnation and the crucifixion.

Bonhoeffer himself died before he could fully flesh out the connection between deep Christian communal life and a discipleship that is more worldly than the world. He bequeaths that conundrum to us, and in many ways the question is the most valuable aspect of his legacy.

If we take up Bonhoeffer’s challenge, then we can learn what it means to abide in a church whose practices teach us to love the world more than the world loves itself, all for Christ’s sake.