The telephone rang in the middle of the night. I was not sure whether I was dreaming but soon discovered that it was very real. A tragedy had befallen a congregant. I prepared myself and hurried to the hospital.

Close family members had arrived, some in tears. Fear was in the air, and uncertainty filled the space. The cold temperature, the loud beeps and the bright lights stood in stark contrast to the warm and quiet dark through which I had traveled.

Hours passed. The patient stabilized, but the prognosis was uncertain.

Then a neighbor-friend arrived, stood at the bedside of the patient, looked down tenderly and offered words of assurance: “Everything is going to be all right.” The neighbor-friend continued: “God does everything for a reason.” I was so angry that I did not know what to do.

The neighbor-friend was trying to be helpful. This well-meaning Christian was trying to offer hope. But how was it that the neighbor-friend could walk into the hospital room, stand at the side of the bed and look down on a seriously injured and frightened person without seeing the need for more than bland assurances?

Christians are resurrection people. “Up from the grave he arose,” we sing, and “life is worth the living just because he lives.” God raised Jesus with all power in his hand, we proclaim. All of that is true.

We live in the hope of the resurrection. And in this coronavirus context, preachers and Christian people are offering hope … or so we claim.

Media platforms are saturated with pontification, propagandization and proclamation all designed to give people hope -- whatever that is these days. But simply saying that things are going to get better or encouraging folks to hang in there or anything similar is neither hopeful nor helpful when the situation is dire.

There is generative power in the spoken word. Words can make things happen. Telling people that we all need to practice social distancing, cover our coughs and stay healthy at home, that we are all in this together, is true. But it doesn’t address the realities, for far too many, that predate this pandemic and are devastating within it.

What do we say to folks whose homes do not have comfortable -- or even adequate -- utilities, groceries or security?

Some people are bored being at home. Some people are gaining weight because they are snacking while binge watching TV or streaming services. Some people are inconvenienced because they cannot do what they want to do.

Some people are weary of being in the same house or apartment with others and are retreating to their own rooms to avoid someone else getting on their nerves. Some people, who have lived with the unearned inheritance of privilege, are experiencing fragility for the first time in their lives.

I get it. Life is uncomfortable. But for many, life is unbearable.

Our communities, country and world are filled with people who are not snacking, because they live with food insecurity daily. They are not binge watching anything, because they did not have access to that before the medical, social and economic crises from COVID-19.

They are not retreating to another room, because they are crowded into inadequate, substandard or slumlord-owned housing. Many, lacking even that, are living on the streets, under bridges and in shelters.

Many live in contexts of physical, sexual and psychological abuse. Domestic violence is rising. Substance abuse and addiction are escalating. Depression is deepening.

Sheltering in place is unbearable for many, those for whom being healthy at home has always been unimaginable. What hope shall we offer to them?

How might those of us who are blessed to be able to be healthy at home really bring hope in this season? Some are offering money to ministries and service providers. Some are volunteering. Some are practicing safe behavior to help “flatten the curve” of infections. Some are calling to check on vulnerable friends and family. Keep up the good work!

But there are bigger questions. How might we work now to address systemic injustices that make so many vulnerable? How might we work to ensure that people who are black and brown and First Nation and people who are living in poverty can get access to health care and healthier food?

How might we work to ensure that people are not forced to live in substandard housing? How might we work to ensure that people can find rescue from abuse and recovery from addictions?

Everything is not going to be all right unless we decide to make things right.

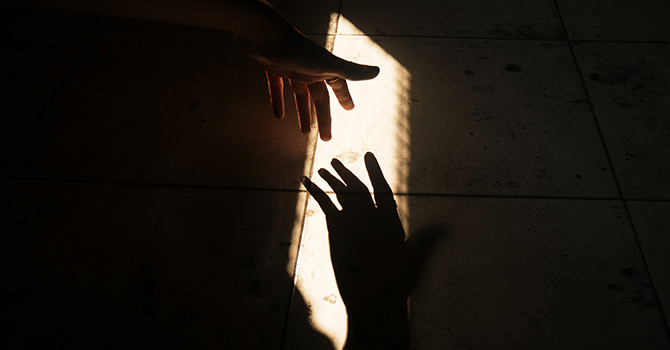

I was livid when the well-meaning Christian neighbor-friend stood at the hospital bed of someone who did not know what the future might hold -- or whether a future might exist at all -- and offered hope. If something needed to be said, it could have been a question: “How can I help?” Or “How can I pray?” Or a promise: “I will look in on your family.”

I am trying not to be incensed at politicians, preachers and media personalities who attempt to make people feel better and offer hope through their videoconferencing and multimedia messaging. But hope requires more than rhetoric.

We have to attend to the immediate crises and work for the next season simultaneously. We have to pray and work. We have to walk and chew. We have to pause and push forward. We have to offer compassion and ensure liberation. We have to speak and act. Then, by God’s grace, we will be available to offer hope -- and help.