Black women have always been called. For generations, we have pastored as evangelists, intercessors, teachers, midwives of faith, and community builders. We preached without pulpits, shepherded without titles and carried congregations without recognition. Often denied ordination, we led anyway.

More and more, Black women are being officially appointed to the position of pastor, from small congregations to historic pulpits. They are also working as ordained ministers across many contexts, like hospitals and nonprofit sectors. This awakening, though well overdue, also carries significance that deserves deeper attention.

I say this from experience. There is a cost in being the “historic first.” The appointment often comes with theft and quiet exploitation, where your work is used, your ideas repackaged — and yet you remain unpaid, uncredited and unseen. Institutions issue press releases that praise your appointment even as actions betray both their words and God’s will.

As a Black woman leader in ministry, I’ve been a pawn in someone else’s strategy, never told I was even in their game. Oftentimes I have been forced into administrative roles and mentored to remain in my place. The pressure to do everything with nothing is a quiet violence I endured across church and secular spaces.

While interviewing Black women pastors for research and through my work with Black Women Write for Freedom, I have heard many painful stories. One woman shared that she was sent to lead a congregation after a male pastor abruptly stepped down mid-year. For more than two years, she carried out every pastoral responsibility: preaching, offering pastoral care, managing the budget and leading the church. Yet she was denied both the benefits and the official title of senior pastor. Despite feeling deeply slighted, she continued her assignment unrecognized and unprotected with full awareness that she was being treated unfairly.

What happens to the mental and spiritual health of Black women when they realize they were chosen not to lead, but to clean up? Not to thrive, but to survive? Not to partner, but to be admin support? The appointment itself is not enough; there must be support and belief in the calling from the congregation and those who appoint.

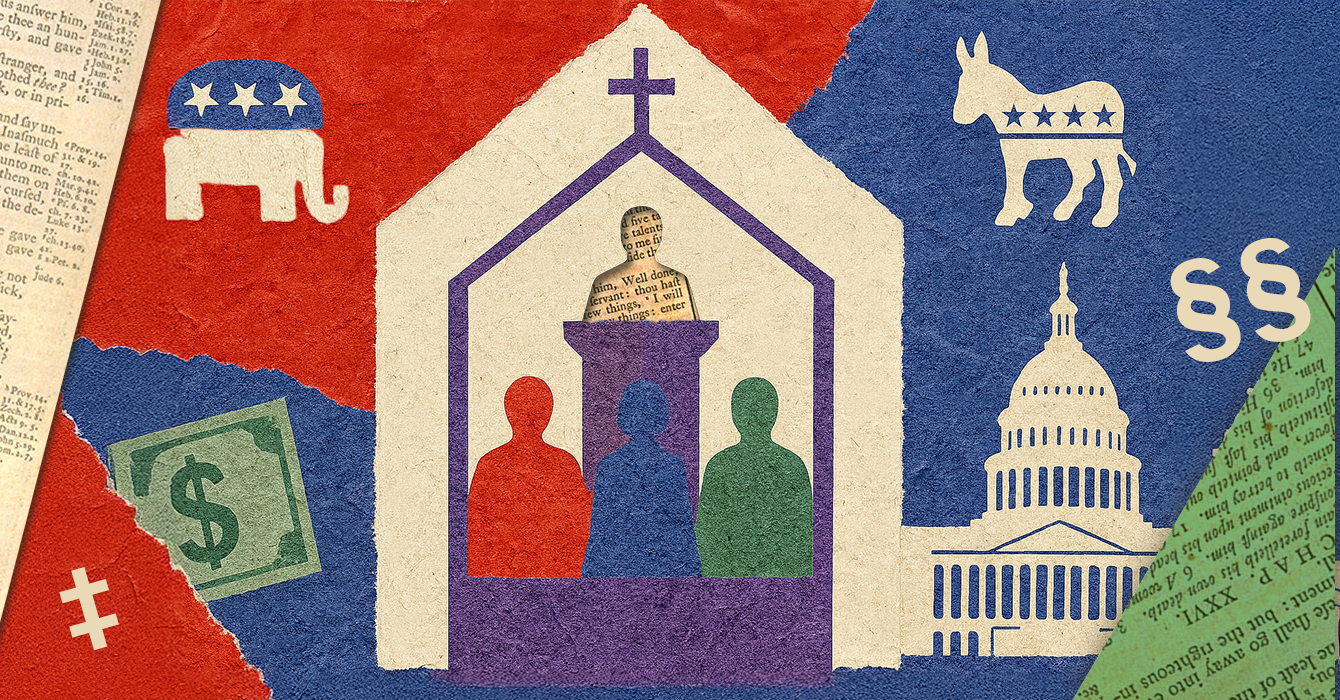

When denominations send Black women into churches that male leaders have damaged and ask them to rebuild from the wreckage, we are being thrown into the deep end and expected to swim, often with little to no support. And when things don’t turn around fast enough, the blame quietly shifts to us. The system asks us to revive dying churches without providing what we need to thrive.

I am deeply concerned about the well-being of Black women in church leadership. I often find myself watching with one eye closed — not because I don’t believe Black women should be in positions of authority, but because in my experience institutions are hard to trust. The celebration of our presence is not always matched with the protection or respect needed to allow us to succeed.

Black women continue to face second-guessing, diminished authority and outright dismissal. We are called “sister” instead of “reverend.” We are asked to preach from the floor rather than the pulpit. We are made to feel, explicitly or subtly, that we do not belong. One pastor said it plainly: “There’s this idea that Black women don’t have to be loved or appreciated.”

I spoke with Black women serving in historically Black denominations and in predominantly white ones, often in what are called cross-racial or cross-cultural appointments, and a clear pattern emerged.

Even when Black women are appointed, boards and leadership bodies often function in ways that undermine us. The systems that should support our leadership can, instead, work against us. Whether through gatekeeping, unequal pay or the absence of spiritual care, the message remains clear: You may be present, but you are not fully welcomed, and you must labor twice as hard for what others receive with ease. One pastor, reflecting on the emotional toll, said, “You can have the tools and intelligence, but if your soul is not protected, that’s dangerous.”

What has been most helpful to me, and to other Black women leaders I know, is being told the truth of what the work will actually require. Too often, that truth is camouflaged by shame, manipulation, or fear that leaders won’t come or stay if they know what they’re walking into. But withholding reality does more harm than good.

We need honesty. We need mentorship. We need resources. We need trust. These are not extras. They are the foundation that allows us to lead, stay well and do the work with integrity.

This is why networks like the RISE Together Mentorship Network and WomanPreach! Inc. are essential. Black women need holistic support: mentorship, mental health care and tangible resources. Without that, the appointment alone can feel more like a setup than a step forward.

Black women are not just navigating unjust systems; we are imagining and building new ones. When we are met with equity, sacred space, honest communication and tangible resources, we are free to lead from our deepest strength.

We are not projects to manage, tokens to showcase or obstacles to overcome. We are full partners. It’s time to move beyond symbolic inclusion. We deserve environments that invest in our well-being, honor our authority and equip us to thrive.

We have always answered the call, leading with vision shaped by generations of resilience. Now, systems and communities must answer our call with trust, equity and real partnership. As one United Methodist woman pastor said, “No place is perfect, but every place doesn’t have to be hell.”

The appointment alone is never enough. Perhaps someone in leadership will read this and have enough faith to believe that our experiences are enough. As one woman shared, “I don’t want future Black women pastors to endure what we did.”

Our faith compels us to go, to create and to innovate — regardless. But it would be holy for others to join us, not as gatekeepers, but as co-creators.

Because when systems fail to support us, when justice is delayed or denied, it doesn’t just harm Black women — it disrupts what God is trying to do through us. These disruptions are not only institutional; they are spiritual. And too often, they result in unexpected and cruel experiences, not because we weren’t called, but because we weren’t cared for.