Katharina Wilkins still passes on things like alcohol and Facebook during the season of Lent, but what’s really important to her is giving up needless car rides and investment in fossil fuels. That’s because, for the third year in a row, Wilkins is participating in the annual Ecumenical Lenten Carbon Fast.

“I have done Lent before, but in comparison, there’s so much more sense of purpose now,” said Wilkins, a member of the Congregational Church of Weston, Mass. “It certainly is still an exercise in self-discipline in many ways, but somehow it fits better into a bigger picture.”

The Carbon Fast was started in 2011 by New England Regional Environmental Ministries (NEREM), which describes itself as “a loosely affiliated group of Christian environmental activists from throughout New England.”

It asks Christians to deepen their commitment to the fight against climate change between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday.

Participants receive a daily email with suggestions for reducing activities that emit carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases, advocating for change, and connecting with the broader climate movement. This year’s Carbon Fast has 3,800 participants by email and 2,350 via Facebook from at least 34 countries.

Traditionalists may dismiss the Carbon Fast as a quirky way for liberals to rebrand the church, but its organizers believe that Christians have a deep, biblical obligation to care for God’s creation.

They also hope that the church can reprise its historic role at the forefront of transformative struggles like the civil rights movement -- and maybe even come to have fresh relevance among socially conscious millennials.

“For me to give up chocolate -- sure, it’s an exercise in self-discipline, and that’s great,” Wilkins said. “But is that really the thing that my life needs to happen the most? Or that life in general needs to happen the most?”

Repentance on a larger scale

The Rev. Dr. Jim Antal, the conference minister and president of the Massachusetts Conference of the United Church of Christ, helped found NEREM in 2010 and writes the Carbon Fast's daily messages.

“I’m 63 years old,” Antal said, “so I think of all the 63 seasons of Lent that I have participated in. Virtually all of them have encouraged individual members to focus on their own personal need for repentance.”

At first, the Carbon Fast was little different. That started to change in its second year, when organizers added two entries per day -- one for individuals and the other for congregations.

They also started encouraging participants within congregations to form discussion groups and added more entries aimed at getting participants involved in the broader climate movement.

The goal is to reduce carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas driving human-made climate change. It is created when people burn fossil fuels and clear forests. In 2013, mean atmospheric carbon dioxide reached more than 395 parts per million (ppm), according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Many climate scientists believe that the safe upper limit is 350 ppm.

This year, each week of Lent has a different focus. Themes so far have included public witness, simplicity and fossil fuel divestment. One link has an online calculator so participants can figure out the carbon cost of their current lifestyle and develop a goal to reduce it. Other suggestions range from flying less and living more simply to talking to a congregation about divestment and joining with others to protest the proposed Keystone XL tar sands pipeline.

“That shifts the consciousness of what Lent is all about from me and my personal repentance to a larger scale. It begins to ask questions about, ‘What about us? What about humanity? What about our congregation? What about Christians in general?’ That was an important shift in the Carbon Fast itself, to begin to ask these larger questions,” Antal said.

As a Christian minister, Antal is acutely aware of the questions’ significance. He often tells other ministers that every third sermon should be about the climate. When they look at him in disbelief, Antal lays out what he believes is at stake for religious leaders: if every third sermon isn’t about climate change now, he tells them, then within 15 years every sermon will be about grief.

The gospel of climate change

Antal sees public witness on behalf of the climate as inseparable from the broader work of building the church and proclaiming the gospel.

“The thousands of young people through 350.org who have showed both surprise and respect at my leadership -- getting arrested a couple of times at the White House, and other brands of leadership -- it opens their eyes to say, ‘My goodness, maybe there is something in the church,’” he said.

The Carbon Fast’s popularity has certainly expanded beyond the Massachusetts church, and Antal hopes the Massachusetts Conference’s prominent stand on climate change will convince increasingly secular young people that the church has an important role to play.

“As churches voice their concern for future generations and begin organizing their towns and lobbying Congress and the White House to pass laws to protect the earth, ‘nones’ will begin to partner with church folk,” he said. “It’s already happening in Massachusetts, because the United Church of Christ has been one of the loudest public voices on behalf of the climate.”

That public witness is a big part of what attracted Wilkins, who grew up Roman Catholic, to the United Church of Christ.

“I think the reason I ended up in the UCC is that this church ties in things that I think about anyway with my faith -- social justice issues, the environment,” she said. “For me, [the Lenten Carbon Fast] is really close to my faith, because it’s in the end about loving all people. How could I love all people if I didn’t care about people in island nations or people who get their land taken away by a pipeline?”

Her words recall the verses from the prophet Isaiah that many Christian churches read to mark the beginning of Lent:

"Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?" (Isaiah 58:6-7 NRSV)

That sentiment is familiar at Wilkins’ church, where the Rev. Dr. Joseph Mayher regularly preaches on climate change. The church has a strong environmental action group, and it even hosted two talks by 350.org founder Bill McKibben in 2011.

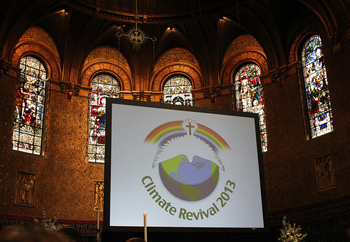

in April 2013 at Old South Church in Boston for a

climate revival.

Photo courtesy of the Diocese of Maine

“The key is to help pastors recognize that it really is about being an anchor for moral witness. It is certainly not about institutions for institutions’ sake,” explains Antal. “There is a world that needs to be changed. If you spend a lot of time focused on climate the way I do, change can’t be big enough and can’t be soon enough.”

That may seem like mission drift when mainline churches are facing existential threats. According to the Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, the number of white mainline Protestants declined by three percentage points between 2007 and 2012 alone. Church closures tell the same story: the Barna Group found that some 8,000 mainline congregations across the country closed their doors between 1950 and 2009.

Still, Antal believes the church has a critical role to play in creating that change. Drawing on examples from the civil rights movement and other causes, Antal argues that religious leaders have long been at the forefront of America’s fights for social change.

“We have the capacity to do it,” he said. “We just have to manifest the determination.”

It’s a message that the Rev. Reebee Girash gets loud and clear. About three years ago, she had a “wake-up moment” that she credits to public witness by Antal, McKibben and Religious Witness for the Earth. Now, she is active in the climate justice movement and serves on the board of directors for the Cambridge-based Better Future Project, which convenes 350 Massachusetts.

“In a time of mainline shrinkage where we’re all anxious about our institutional survival, it can be really hard to step out into the world,” Girash said. “And yet if we really want to be serving the world and relevant to the world -- and particularly relevant to socially conscious young adults -- this is a place we need to go. God didn’t tell us to hide our lamps under bushels.”

Institutional commitment to activism

Antal devotes 15 to 20 percent of his time at the Massachusetts Conference to climate work, with the blessing of its board of directors and member congregations. That includes national speaking engagements, running the Carbon Fast and even getting arrested in front of the White House protesting the Keystone XL pipeline with groups like 350.org and the Sierra Club.

Photo courtesy of Shadia Fayne Wood

Last year, the conference took an even bolder stance by spearheading a successful effort to make the United Church of Christ the nation’s first religious body -- and the first national body of any kind -- to divest from fossil fuel companies.

People concerned about the scientists’ predictions on climate change may wonder whether efforts like the Ecumenical Lenten Carbon Fast aren’t too little, too late. Others might accuse it of giving middle-class, white liberals a way to ease their guilt without engaging in real, systemic change. But Antal sees things differently.

“I tell congregations, ‘I want to trade a shriveled hope that you will recycle, or maybe walk or bicycle a little more instead of using your car -- I want to trade in that tiny hope for a much grander hope. … I have 100 percent confidence that the people in this congregation know exactly where the railroad tracks are, and that soon enough you will put your bodies on the tracks and block the transport of oil from the Canadian tar sands to our processing plants,’” he said.

He’s fully aware of how radical that sounds.

“I know I’m way out ahead,” he said. “That’s what leadership is all about. Leadership is about being far enough out ahead to cast a vision, to extend the horizon and to then invite people to come with you.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- The Carbon Fast encourages individual and collective repentence. In your organization are there ways to broaden individual practices to a “larger scale”?

- For Jim Antal, innovating on the traditional Lenten practice is a way to make the church relevant. Are there practices that could be made more relevant in your institution?

- The Massachusetts UCC supports Antal’s work on climate change, even though it doesn’t fall within traditional ministry. If you could spend 15 to 20 percent of your time on a project, what would it be?

- Antal sees his role as a leader as being “way out ahead” of those whom he leads. What are the pros and cons of this leadership style? Would it suit you?