Touch the pews with your hands, the Rev. Troy K. Venning told the crowd of grassroots activists gathered at Quinn Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church on a November evening.

“It has been said that the oils of our ancestors are on these pews,” Venning said, quoting the chief architect working on the church restoration. “You never know who was sitting where you’re sitting.”

It’s an illustrious roster: Quinn Chapel has hosted figures such as Ida B. Wells, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Frederick Douglass, in addition to all the faithful who have been part of its long history. It is the oldest African American congregation in Chicago, dating back to seven people who gathered for prayer in 1844.

Under the leadership of Venning and his predecessor, the congregation has undertaken a restoration of its historic building and its connection to the neighborhood, revitalizing itself in the process. Quinn Chapel is not only a place to learn about the past but also a place where people can find connection in the present.

“There’s a West African teaching that urges us to reclaim what the past offers so that we can walk into the future with clarity and courage,” Venning said to those gathered for the November meeting about the city of Chicago’s budget.

The meeting was convened by United Working Families, an independent political organization funded by labor unions. Several members of the city council attended, as did Mayor Brandon Johnson. For all of them, UWF is a source of grassroots political support.

“This church is no stranger to the fight for the moral good,” Johnson said, recounting Quinn Chapel’s role as a stop on the Underground Railroad. “Thank you for understanding the collective assignment of liberation.”

Operation Midway Blitz

In the weeks before the meeting, federal agents were swarming the city and detaining thousands of Chicago-area residents in immigration-enforcement raids as part of Operation Midway Blitz.

Groups formed across the city and suburbs seeking to prevent their neighbors from being taken, actions that recall the role of Quinn Chapel members in resisting the Fugitive Slave Act in the 1850s. The congregation was part of a group of Chicagoans who formed patrols to thwart catchers trying to return people to slavery.

“There was a group of people from this church who started a vigilance society,” Venning said, “to keep people free.”

During the Great Migration in the first half of the 20th century, the church building was a welcoming center for people leaving the segregated South. The late Timuel Black, a historian born in Alabama and raised in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, said when his family arrived in the city, their first stop after Union Station was Quinn Chapel. They had been told that people at Quinn would tell them where to go next, Venning said.

Venning emphasizes that Quinn Chapel’s story is not only Black Chicago history but U.S. history. Susan B. Anthony spoke at Quinn about giving women the right to vote. A two-seater pew from the sanctuary is at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“Quinn Chapel has always been more than a church: It’s been a landing place, a launching place, a liberating place for generations seeking freedom, safety and belonging,” Venning said.

Does your congregation have a history that inspires action in the present?

Vision for restoration

Even with its historical significance, by the late 1990s Quinn Chapel was in danger of closing.

Not only had the congregation shrunk, but the grand building in the South Loop neighborhood near downtown urgently needed repairs. Rain and snow were seeping in and damaging the interior, among other problems.

The Rev. James Moody became pastor in 2002 with a vision for restoration. Under his leadership the congregation grew not only in numbers — from 35 to 400 — but in energy. With concerted effort from his wife, First Lady Corlis Moody, and the restoration team, the congregation began to repair the historic building.

Corlis Moody oversaw grant writing and connected with historic preservation groups. James Moody, who is now a presiding elder for the AME denomination in the Chicago North District, stressed that it was not only the leadership of the church who aided in their success but “specific members with connections and courage.”

Charlotte Flickinger, a church trustee, guided the Moodys through making connections with the state legislature.

“She worked tirelessly and walked those halls and knocked on those legislators’ doors,” James Moody said. Flickinger’s efforts helped Quinn Chapel have $9.4 million earmarked from the state of Illinois for the historic restorations.

Many of the grants received over the years could not go to religious institutions, so Quinn Chapel set up a 501(c)(3) nonprofit specifically for restoration, Moody said.

Who in your congregation has the skills or connections to help further your mission?

Work began with the roof. The phases after that have included two renovations of the fellowship hall, the addition of an accessible ramp and elevator, and creating new offices, meeting rooms and music practice space.

About $12 million has been raised so far. In addition to state funding, they received multiple grants, including through partnerships with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the National Fund for Sacred Places. Through energy company ComEd and environmental groups, Quinn Chapel had a $650,000 high-efficiency HVAC system installed, cooling its limestone building with air conditioning for the first time in summer 2023.

A future restoration phase will focus on the historic second-floor two-level auditorium, which is also their sanctuary. Its tin ceiling is one of the largest in the nation. There will also be work to fully restore a mural at the front of the sanctuary, where Jesus has dark brown skin and a golden halo, arms outstretched.

The mural and stained glass also reflect the congregation’s history. From what church leaders have learned, the 1904 mural is one of the first North American depictions of Jesus as Black. One of the six angels in the mural was modeled on the way a girl in the congregation listened during worship.

And the Rev. Sheryll Brown-Venning, first lady and a minister of Quinn Chapel, sees a constellation of stars when she looks at the bright spheres dotting the stained-glass windows that have graced the building since it was constructed in 1892. It reminds her of those who fled north following the drinking gourd, also called the Big Dipper.

Hearing the creak of the wood and touching the pews “is majestic to me,” Brown-Venning said. When her husband encouraged her to preach, she felt honored “being able to stand behind the same pulpit that Martin Luther King stood behind.”

Architectural and aesthetic value isn’t the only reason to restore historic church buildings, said Robert Jaeger, president of Partners for Sacred Places, a Philadelphia-based organization. It also has economic and social benefits.

What story does the art in your church building tell?

The average urban historic congregation generates $1.7 million annually in value, with 87% benefitting the community beyond its members, according to a 2016 study by Partners for Sacred Spaces collaborating with the University of Pennsylvania. (For rural congregations, the figure was $735,000 annually, a separate study showed.)

That includes employment of staff and drawing visitors who may also patronize local businesses. There is ecological and recreational value in the green space around churches, Jaeger said. Overall, the study looked at more than 40 factors.

Preserving historic sanctuaries also allows them “to do new things for those who are in need,” he said. He believes most congregations want to do that, but repairs can feel like an obstacle to starting programs.

“If you can help invest in that building, invest in accessibility,” as well as in repairs and maintenance, he said, “it benefits outreach.”

Without its restoration efforts, Quinn Chapel could have closed, Jaeger said. “Now it’s a strong congregation that has done a lot of good for that neighborhood.”

Have you assessed your congregation’s community impact? If not, how might you approach such an assessment?

Leadership for the future

When Moody began preparing for a leadership transition, he thought of Venning, who had grown up at Quinn Chapel and was an intern there while a student at Garrett Evangelical Theological Seminary. Venning then served as a pastor of three congregations in Florida.

Moody kept in touch and heard about Venning’s style of pastoral leadership, including at spoken-word poetry events and other venues beyond traditional church settings.

Moody also looked around at Quinn Chapel’s leadership and saw they were mostly people older than 50, he said. Leaders began the transition process with the steward board by inviting more laypeople in their 30s and 40s into leadership roles.

“Those leaders, those baby boomers, actually embraced the idea because they could see Quinn existing years later, decades later,” Moody said.

After a five-year transition process, the congregation asked Venning to come back to be executive pastor in 2019. Venning and Brown-Venning trusted God’s call through a difficult transition for their family, amid a period of deep personal loss and the start of the COVID pandemic. The AME district’s bishop appointed Venning to be senior pastor in 2021. There are still 400 members on the rolls, with 80 to 120 people at Sunday worship.

Building on the work the Moodys had done, Venning helped the finance team make necessary updates, including moving to online banking, with checks and balances in place. This was especially important for receiving and managing grant funds they had been awarded.

Venning sees the congregation as being like a train station. People arrive from different places and need a moment to rest before going to their next destination.

“Whether this is your final destination or you’re headed somewhere else, at least you should be able to find the things that you need to keep moving,” Venning said.

Train stations are also places where different people cross paths, bringing everything they’ve carried.

“We’ve always been a place to bring the haves and have-nots together,” Venning said. “I’m a firm believer that when people get to Quinn, they’re here because Quinn needs something that they brought with them, and they need something that we have now.”

The joy of a historic church

Plans involve looking to the past and the future.

The surrounding neighborhood was once the location of a large number of railroad depots and stations. There were also several public-housing developments located nearby. In recent decades, developers have built a lot of high-end housing, along with retail.

In addition to the church, Quinn Chapel owns a lot across the street and five adjacent lots on a nearby major corridor, State Street. In a dense area of the city where there is not much parking, those lots have been generating revenue for the congregation.

Another source of income has come from being a filming location for television and movies. Chicago has a multimillion-dollar TV and film industry, and studios pay restaurants, hospitals and other buildings to film scenes there. Recently, Quinn Chapel’s fellowship hall was used as the setting of Al-Anon meetings in the television series “The Bear.”

The congregation plans to turn property it owns diagonally across from the church building into a mixed-use development with housing, office space and parking. In the church, the first floor will have a bookstore that will sell books that are banned or “someone said you shouldn’t read,” Venning said.

Blocks away from the historic Chess Records studio where some of the greatest blues and R&B artists recorded their music, Quinn Chapel will have a recording studio for artists such as Adrian Dunn, Quinn Chapel’s director of music, worship and arts.

Christopher Wilson, associate music director and administrative assistant, studied audio design and engineering and does audio editing. Now a trustee as well as a staff member, he joined in 2015 as a college student.

Are there unique opportunities for fundraising based on your location?

“We’ve stood the test of time and continue to do ministry,” Wilson said. “To grow from a seven-person prayer band into a church that has birthed other congregations — I think that’s pretty remarkable.”

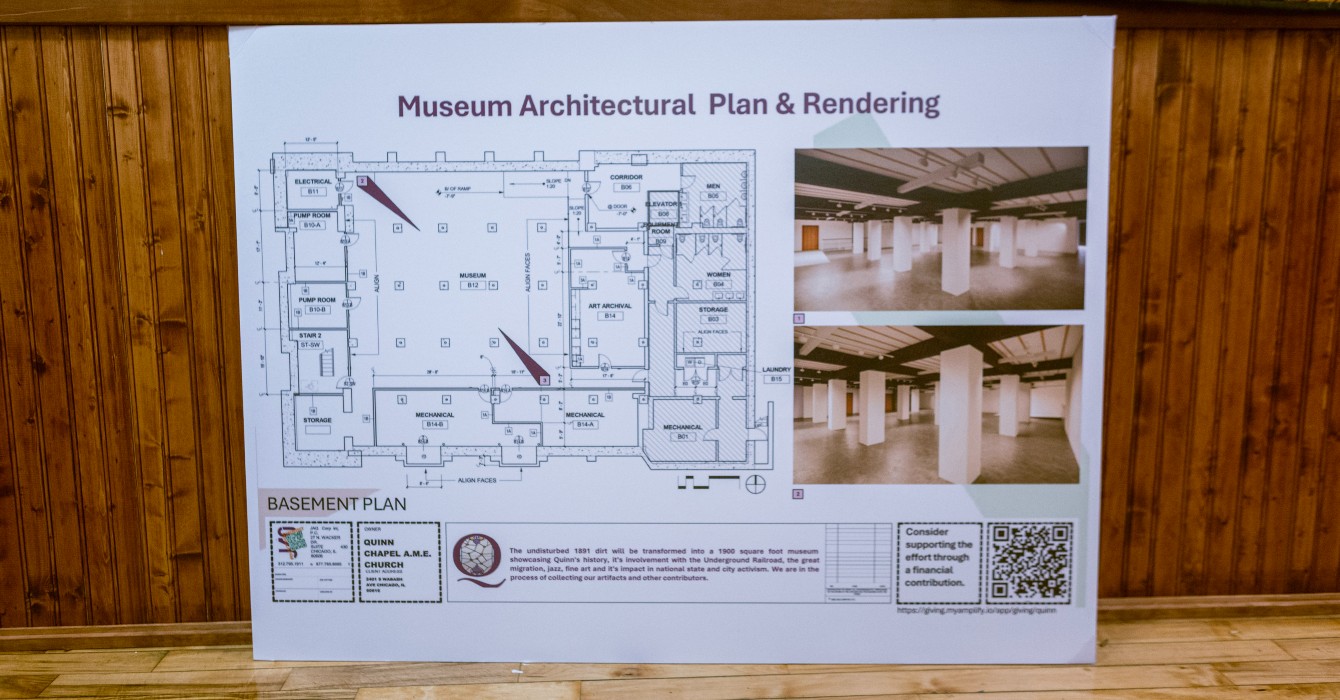

The congregation’s role in the Underground Railroad and the Great Migration will be a highlight of a new museum in the building. Excavating the basement will add 4,500 square feet of additional space. It will have an archives room, another meeting and arts space, and a museum that they hope to open to the public in 2027. It will include artifacts and stories from how the congregation has intersected with broader history.

“For folks who have the joy of being able to pastor in historic spaces, it’s about finding your story and being able to tell it,” Venning said.

The meeting about the city budget in November was one of the many Quinn Chapel hosts. Their main-level event space hosts art installations, movie screenings, educational events and more. Larger events, such as a mayoral forum in the last election, have taken place in the historic auditorium. Some weeks there are events most weeknights and Saturday as well; Venning said that it’s a mistake to focus on Sunday only.

Connecting Quinn Chapel's legacy and present, Venning recalled the West African teaching of embracing the past’s lessons to move into the future.

“The Sankofa bird looks back while its feet face forward,” Venning told the crowd that evening in November: “We embody what our ancestors practiced: faith in action.”

How might you find your congregation’s story and tell it?

Questions to consider

- Does your congregation have a history that inspires action in the present?

- Who in your congregation has the skills or connections to help further your mission?

- What story does the art in your church building tell?

- Have you assessed your congregation’s community impact? If not, how might you approach such an assessment?

- Are there unique opportunities for fundraising based on your location?

- How might you find your congregation’s story and tell it?