As leaders, how do we decide what to fix and what to toss? Or put another way, what to mend and what to replace?

Over the past few years, I’ve taken up textile mending as both a spiritual practice and a practical skill to waste less in a sinfully disposable economy. In mending, I’ve found an embodied knowledge that has been missing from much of my life.

Christianity offers the promise of repair. My ministry is devoted to repairing broken relationships and repairing the wounds in the body of Christ. But some days, I have no idea whether I’ve done anything to aid in the repair. And some days, I fear I may be making things worse.

By contrast, when darning a sock, I can see and feel what I’ve done. Mending holds out the possibility of both utility and beauty, without the idolatry of the new or the wasteful disposal of the old. Mending appeals to our desire for visible results: Can we make this work again? Can we make this beautiful?

I recently ran across a guide for textile repair from the University of Kentucky. I love it because it walks me through a series of questions to discern whether to mend or not to mend. I see a clear connection to my work at the Massachusetts Council of Churches, where I serve as the executive director.

Whether I’m dealing with the unraveling of a well-worn sweater or the unraveling of our council’s governance structure, these questions serve me well.

The first one is crucial: How extensive is the damage? Before I can repair anything, I have to acknowledge that it is broken.

At the council, I knew that our current governance structure wasn’t working, but I had been slow to respond to the signs of deterioration. We were struggling to gather a full board. We were straining to do the work. We had already suspended our constitution, piloted a nimbler structure and then made a massive constitutional change. Barely two years later, it was hard to admit that things were falling apart again.

The mending guide’s second question calls for self-evaluation: Do I have the knowledge and skill to repair the garment, or do I need to take it to someone else?

At the council, I struggled to see how frayed we were. It was only when I met with my board president and another trusted outside adviser that I could really see the extent of the damage. I kept thinking that if I just emailed more, or emailed less, or asked the question differently, or scheduled the meeting sooner or later, we would be able to make it work. I needed other eyes to see that we had already tried those changes and we needed to find another way forward.

The third question calls for evaluation of the item to be mended: Is it worth repairing? This is a tough one to answer honestly.

My years of stitching up moth-eaten sweaters have taught me that mending is an affirmation of worth. We mend what we value and what we cannot afford to replace.

For now, the council has decided that our current governance structure is worthy of repair -- worth the time, skill and attention required to fix it.

My mending has taught me also that things we use fall apart. Things we love wear out, and there’s no shame in that.

This winter, for example, I repaired a jacket for my wife. It wasn’t her occasionally worn, formal coat that needed repair but her most loved, everyday hoodie. Because she puts on this hoodie every day after school, the cuffs were frayed and the elbows had worn thin. Moths had eaten some bits on the front, nibbling at spilled food.

The more I mend, the more predictable the places of repair become. Not surprisingly, seams and places of movement and strain are often the spots that first need fixing.

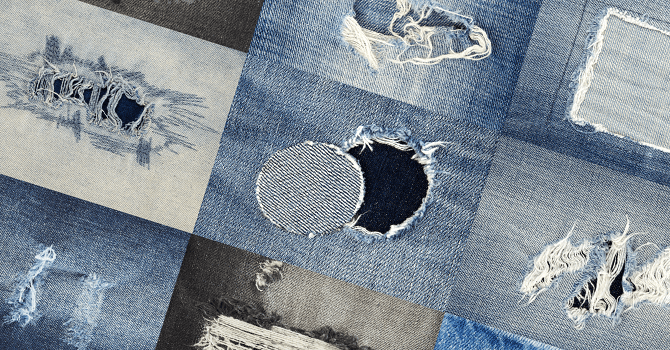

This is true of our churches and the structures within them as well. If they are in need of repair, it may be because they are often used. And that need isn’t something shameful. It’s natural, in the same way that our jeans wear out at the knees, not because they are bad, but because they are well-loved and useful.

To be sure, it is true that things sometimes fall apart because they were poorly constructed or made of cheap materials.

For those invested in leading historic institutions in matters of equity, inclusion and diversity, there is honest work to be done in examining how our institutions were exclusively and poorly constructed in the first place. If an institution was initially created to serve only certain people, a patch here and there will not be enough.

Working ecumenically gifts me with experiences of many different Christian communities. And even in my limited view, almost no part of American Christianity feels particularly stable right now.

Indeed, almost no institution in American life feels steady these days. Everything is fraying. God is still very present and, I believe, in control, but there is much that is unraveling and coming undone. It is not yet clear what is being remade.

I had a revelation a few weeks ago reading a 1960s-era mending guide. I stumbled on directions on how to strengthen the seams of a newly purchased garment. The guide anticipated that the garment would wear out and so was planning for repairs even before it was worn.

What if I prepared my heart and my organization for the need to repair again soon, without shame?

In our case, the repair for our governance model is a patch for now. As we’ve intentionally sought to make the racial, generational, gender, denominational and economic diversity on our board reflect more accurately the diversity of the church, we have more leaders with less free time for long, in-person meetings. And we’re all under increased strain.

So we’ve narrowed the board job description to a scope that’s achievable, moving more of the big-picture work back onto our small staff team. I’m not certain this is the right fix, but it’s the repair we’re trying for now.

We likely will need to patch again soon. That is the nature of a well-loved, often-used garment in a season of high friction.