Editor’s note: This is the sixth and final installment in a series exploring how the field of game theory can help church leaders navigate conflict effectively.

“What are you doing? Are you coming back to bed?”

It was a little after 10, and I was pacing around our bedroom. My wife, Melissa, had been asleep but was now very much awake. Sounding both concerned and annoyed, she repeated her question. I had stalled as long as I could. I had to answer her.

“Uh … I’m right around 9,980, and I really want to make 10,000.”

“You have got to be kidding me,” she said as she rolled over and went back to sleep.

But I wasn’t. And I kept walking around our room until I hit 10,000 steps. My Fitbit lit up, bestowing its deeply satisfying, congratulatory buzz. Now I could sleep.

Games are powerful motivators, and they can change our behavior. In light of this potential, the church should embrace the insights of game theory and game design. But the church must do so with care. Even within the gaming community, game designers warn against those who use games to manipulate customers.

“Find the Future,” a game designed for the New York Public Library, shows the way that games can be used for the strategic good of an institution -- and the greater good of a community.

Game designer Jane McGonigal told the story of how she developed “Find the Future” at the launch of the Center for Innovation in Ministry at San Francisco Theological Seminary.

Library staff, seeking to encourage greater youth participation, had suggested ideas such as filling the library with Xboxes or coming up with a PBL (points, badges and leader board) system to encourage young people to check out books. But patrons playing Halo hardly furthered the goals and values of the library. And it turned out that although PBLs would have boosted library usage, both ideas missed what really interested that population.

Through careful listening, McGonigal learned that what deeply interested most of them was writing a book. She created a game that allowed 500 young adults to explore the library’s collections and write essays to be gathered into a book, edited by volunteers from major New York publishing houses and now housed in the library’s rare books room alongside a Gutenberg Bible and an original copy of the Declaration of Independence.

The community I serve, Tualatin Presbyterian Church in Oregon, is embarking on a project to gamify spiritual practices in the hope of deepening our faith.

A small group from our congregation is currently selecting spiritual practices to track, including everything from contemplative prayer to encaustic art. Players will set measurable goals in units of time spent in their chosen practices, offering their time sheets during worship. We will award participants with badges to mark their progress. We will also offer them “quests,” inviting them to try other practices along the way to broaden their experience.

At the end of the year, our hope is that our small community will have spent 10,000 hours in prayer, Scripture reading, hospitality, social justice and acts of beauty. The practices will shape the players, who will have stories to tell about what they learned and how God surprised them along the way.

Margaret Robertson, a game designer who criticizes the unreflective use of games, refers to much of gamification as “pointsification.” Robertson argues that points and badges are the least important aspect of a compelling and engaging game, countering the popular notion that simply adding points and a leader board to business as usual will turn it into a good game. Even leading advocates of gamifying business agree; Kevin Werbach and Dan Hunter, in “For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business,” cite studies showing that the competitive elements of games, employed without care, can actually demotivate and stifle participation.

Certainly, the simplistic use of a leader board is part of the furor over Bishop Will Willimon’s dashboard in the North Alabama Conference of the United Methodist Church. Bishop Willimon argued that these congregational metrics merely reinstituted Wesleyan accountability and couldn’t hurt, given the state of the church.

But especially when linked to professional advancement, say Werbach and Hunter, elements such as leader boards are as likely to cause problems as they are to solve them.

By contrast, when employed playfully and in service of the good news, even a leader board can be helpful.

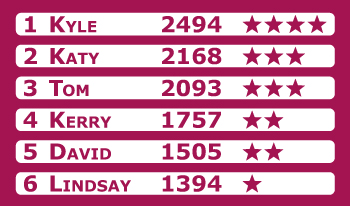

The Rev. Mike Mather of Broadway United Methodist Church in Indianapolis has been keeping the Bible in one hand and McGonigal’s “Reality Is Broken” in the other. For about a year and a half, he and the staff at Broadway UMC have been playing a game designed to increase engagement with their neighborhood. Using a simple leader board, Mather and his colleagues gain points by counting the number of actions each week or month in 12 ministry areas:

1. Visiting people in their homes to lay hands on and bless them and offer prayers of celebration and praise for their ministry: in their lives, their homes, their workplaces;

2. Introducing people to each other because “we see in each of you that you seem to have the same call and claim of God upon your life, and it seems like it would be great for you to know that about each other”;

3. Praying with people: in hospital rooms, on street corners, in alleys, in living rooms, in offices, in car repair shops;

4. Writing letters to people celebrating their discipleship in the life of the world;

5. Anointing people with oil for the challenges that are set before them;

6. Journeying with people to visit someone else: at home, at the hospital, in the workplace;

7. Visiting people to remind them of their baptism (perhaps on a baptismal anniversary);

8. Sharing meals with people and reminding them of the communion meal Jesus shared with his friends on Maundy Thursday, and of Christ’s presence at the table;

9. Offering forgiveness to people who are laboring under guilt and shame;

10. Throwing parties to celebrate the presence and power of the love of God in the people and the parish;

11. Reading specific Bible stories to people whose lives you see in those particular stories;

12. Posting on Facebook to celebrate the discipleship of the people in the parish in concrete and joyful ways.

Each player gets one point for every action (except pulling together a party, which is worth five points). What makes Mather’s game effective is the creative ways his church is trying to engage people in their community. And what makes it fun is that at the end of each month, the “winner” gets to buy all the other players a round of cupcakes. “Whoever would lead must be servant of all” is especially true when dessert is involved.

Mather and I agree that more churches are using games such as these to encourage creative engagement, but we need to hear from you. If you are using some form of gamification in your community, please let me know.

But while you do that, I have to excuse myself. I have to get my steps in before bedtime.