Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a series exploring how the field of game theory can help church leaders navigate conflict effectively.

Perhaps the greatest conflict that leaders face is with ourselves. Paul describes this inner conflict in Romans: “I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do” (Romans 7:18b-19 NRSV).

For the last 10 years of my ministry, I’ve been part of an incredible small group of pastors that meets every Tuesday. We call ourselves a lectionary group, but honestly, most of our time is spent talking through challenges we’re facing, the greatest one being finding the motivation to persevere. I have often said I wouldn’t still be doing ministry were it not for this group.

The claim isn’t hyperbole. There are days when being a pastor can feel more like being an activity director on a sinking cruise ship full of angry monkeys than being a shepherd of souls or a student of Scripture. In our small group, we often discuss how isolated we feel and question what impact our actions really have. Sometimes we believe it would be easier to have a “normal” job and serve the church as a volunteer.

Our small group is not alone.

One study conducted by the Schaeffer Institute found that 90 percent of pastors surveyed felt inadequately trained. The same percentage said the practice of ministry was entirely different from what they had expected. Seventy percent of pastors fight depression on an ongoing basis. Fifty percent say they would leave ministry tomorrow if they had a viable alternative.

Duke’s Clergy Health Initiative has brought to light significant health risks associated with the profession of pastor. The rates of obesity, diabetes, arthritis, high blood pressure, angina and asthma among Methodist clergy in North Carolina are significantly higher than rates in the general population.

In general, a disturbing number of pastors believe that their work isn’t satisfying, rarely experience a sense of competency, feel isolated and question whether they are making a meaningful contribution to something greater. Pastors live with a painful inner conflict: the good we want to do, and feel called to do, we often aren’t doing.

How can playing games address such a serious problem? If you asked game designer Jane McGonigal, the New York Times best-selling author of “Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World,” she might turn this question around to say we can’t really address these problems seriously without talking about playing games.

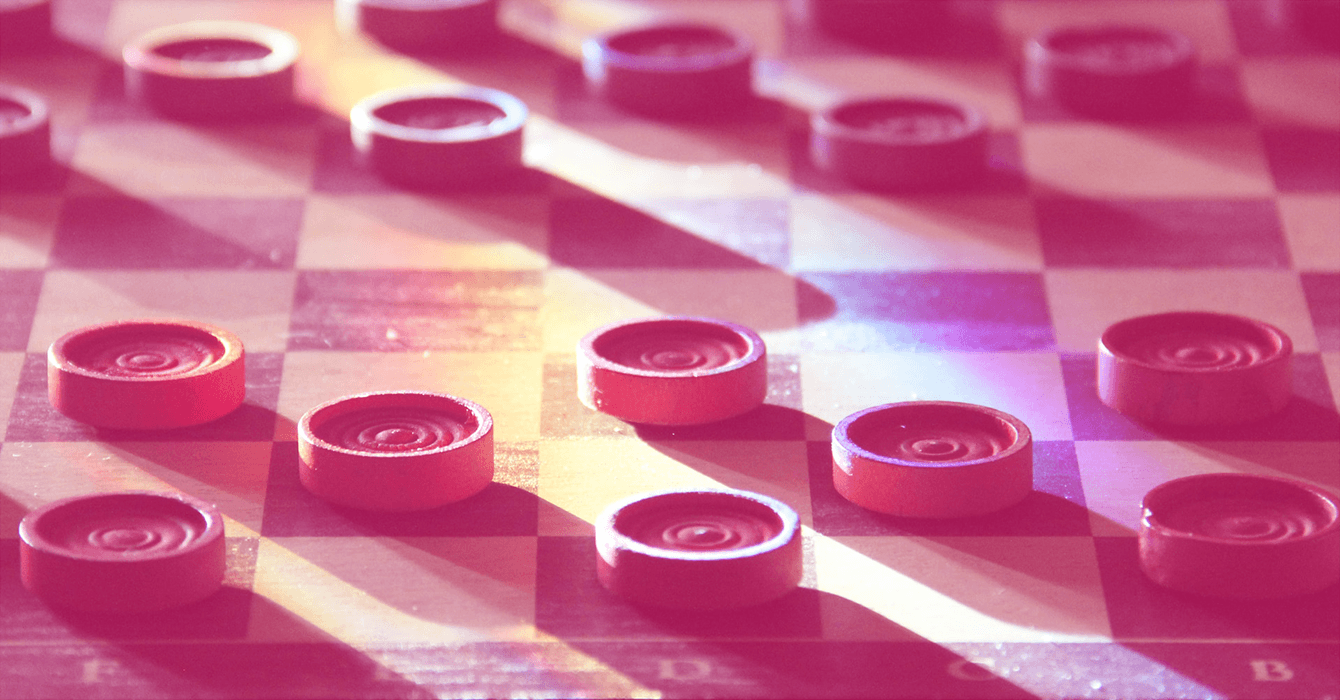

McGonigal is one of the leaders of a movement known as “gamification.” Gamification, the application of game design principles to nongame settings, pervades contemporary culture. While distinct from game theory, gamification furthers the game theory perspective that behavior is affected more by context than by personality. Plus, gamification improves upon game theory by reintroducing the element of playful creativity that is largely absent from the cerebral strategists of game theory.

Chances are, you experience gamification on a daily basis. If you participate in a frequent-flyer program, for instance, you are familiar with accumulating points to earn real travel rewards. If you use a Fitbit or a Nike+, you know all about badges for accomplishments and leveling up, all in an attempt to make exercise seem less like work and more like fun.

Those tempted to dismiss the power of games and gamification, McGonigal warns, are likely to be severely marginalized in the coming years. If you think of gamers as young boys playing shoot’em-ups alone in their rooms, you need to think again.

At the time McGonigal published her 2011 book, 40 percent of gamers were women. The average age of a gamer was 35, and 25 percent of gamers were older than 50. Some sites, with names like GeezerGamers and 2old2play, even cater to “old” gamers. Given that 97 percent of young people consider themselves gamers, these trends are sure to increase.

The church faces both an opportunity and a threat: if we find faithful ways to integrate gamification into church practices, we will have an opportunity to communicate in the lingua franca of current and future generations. If, however, we ignore gamification, we risk relegating ourselves even further to the margins.

The church certainly shouldn’t chase after every cultural fad, no matter how popular. In the case of gamification, though, there are contemporary scholars who point us to ancient voices within our tradition that resonate with this innovation.

Dan Migliore, professor emeritus at Princeton Theological Seminary, urges us to see the act of creation as the “‘play’ of God.” William Brown of Columbia Theological Seminary lifts up God’s playful nature in Psalm 104, even when God encounters Leviathan. Brown quotes Jon Levenson suggesting that God treats the terrifying symbol of chaos as “God’s ‘rubber ducky.’” In his “Theology of Play,” Jurgen Moltmann even ties Christ’s resurrection to play; he notes that the risus paschalis, the Easter laughter, revives all of creation. Since God plays, Moltmann argues, so too should we.

The apostle Paul provides the strongest connection between our theological tradition and gamification.

In 1 Corinthians 9:24-27, Paul employs the metaphor of the Isthmian games, held in Corinth every two years, to describe his apostleship and encourage excellence in the community. Just as the athletes practice discipline and run to win, so too should disciples of Christ practice the way they intend to follow. Nor is this analogy to the Isthmian games unique.

In Galatians 2:2, Paul describes meeting with the other apostles to ensure that he is not running his race in vain. In Philippians 3:13-14, Paul frames living into his call as a goal and a prize. The Pauline community continued using this gaming metaphor even after Paul’s death. Second Timothy 2:5 compares faithful teachers to athletes who play by the rules. Paul and the Pauline community are not only unafraid to draw from the world of games; they lift games up as a way to understand discipleship in the real world.

The Fun Theory, an initiative of Volkswagen, seeks to use gamification to make the world a better place.

One Fun Theory video opens with herds of people mindlessly riding up an escalator next to empty stairs. To see what difference a playful innovation might make, a team transformed the stairs into a life-size piano keyboard that played a note and lit up with each step. They transformed walking up the stairs from a chore into a game. As a result, 66 percent more people began to use the stairs. The video shows some individuals jumping up and down the piano stairs in pure joy. Fun and games turned out to be good for the community’s fitness.

In World Without Oil, a 2007 game created by McGonigal and others, players experienced a world in crisis from an oil shortage. Players employed different strategies to survive the shortage, their actions affecting themselves as well as the other players.

What particularly struck McGonigal was how nearly all the players -- despite spending hours in difficult and bleak landscapes -- reported feeling more optimistic about changing the world at the end of the game. She believes that playing the game helped create what futurist Jamais Cascio calls SEHIs (super-empowered hopeful individuals, pronounced SEH-hees).

The church needs to be in conversation with anyone in the hope business.

Game design theorists believe that games help us in four major ways:

- They improve our sense of making a difference.

- They give us a sense of competence.

- They connect us with others.

- They give us a feeling of being connected to something larger than ourselves.

These are precisely the areas where pastors struggle.

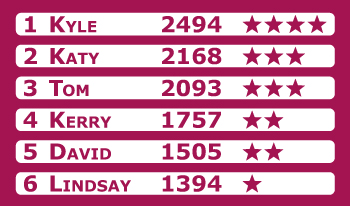

What if there were an app similar to Fitbit or Nike+ in which pastors could connect, track their work, set goals, watch themselves level up, thrive on a little friendly competition and feel connected to a larger community of pastors?

Want to make more pastoral calls? Set a goal. Log them in. Level up. Want to spend more time reading Scripture devotionally? Make it happen. Have you stopped spending time in prayer? Join a group of others online for encouragement. Run in such a way that you may win, Paul tells us.

Will this solve the internal conflict pastors feel between who we are called to be and who we actually are? Of course not. But just as thousands have benefited from gamified health tracking environments, legions of pastors might rediscover the joy of ministry through such a platform.

Feeling stuck and alone as a pastor? Maybe soon we’ll be able to say, “There’s an app for that.”