One of the most powerful assumptions in modern America is that there should be a division between public and private life. In some ways, of course, there has always been a proper sense of the distinction between what belongs between spouses, say, and what should be talked about in a board meeting. But the idea that there are separate spheres in which to live -- and that things crucial to one sphere should not be inside the other -- is a modern development. Such a view of how we are to live cuts much deeper than the sense of privacy brought about by propriety or just plain decency.

In the modern way of dividing life, for example, “religion” is not supposed to interfere in politics or play a part in a secular university classroom, or a public school. Indeed, so widespread is this sense that religion should stay private that many people believe it is enshrined in the First Amendment to the Constitution. That this is false does not take away from the power of the perception: a controversy is virtually assured any time public officials speak openly about the practice of their faith. Religion thus comes to refer primarily to what one believes about God in one’s heart or does on Sunday but not during the rest of the week. In short, the public/private dichotomy has made it possible for us to think that Christianity is what one does or says in a “personal” sphere, in private.

The Acts of the Apostles knows nothing of this dichotomy. In Acts, being Christian is by its very nature a public confession and identity. The Christians were a group whose pattern of life could be seen. In fact, the very word “Christian” was a public word. Contrary to what we might normally think, “follower of the man Christus” (the word’s original meaning) was not first used as an internal self-designation. It was instead a term coined by outsiders, by those who could see a thriving community and needed a word with which to describe them (see Acts 11:26 and 26:28; also 1 Peter 4:16). To be a follower of Christ was to belong to an assembly whose common life was publicly visible.

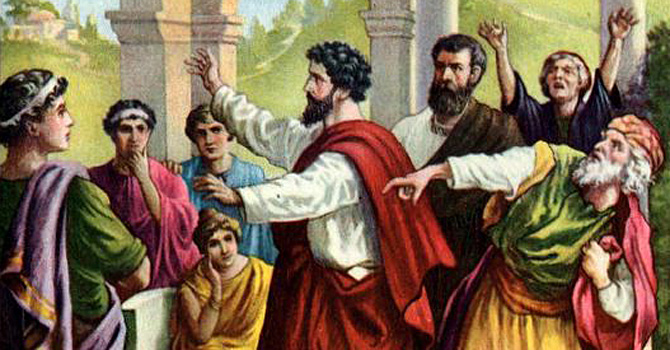

The visibility of the thriving community of early Christians is most dramatically portrayed in Acts through a series of scenes in which we see the Christian community as a force for cultural destabilization in the wider Mediterranean world. In Ephesus, for example, the Christian mission evokes a riot not because of any riotous action on its part but because an Ephesian silversmith can see the impact public Christianity will have upon his business. Because he makes shrines for the goddess Artemis, the silversmith discerns the clash between the religious economics of Ephesus and the burgeoning Christians. Conversions to the way of life proclaimed by Paul will drastically reduce the demand for shrines of Artemis. Far from being a publicly innocuous, purely “spiritual” movement, therefore, the Christians in Acts were consistently in the public eye. Indeed, in Philippi, Athens, Corinth, Thessalonica, Jerusalem and elsewhere, the Christian presence is disrupting enough that the Christians are hauled before the political authorities and forced to give account for their behavior. Simply put, this need to give account could not occur were the early Christians to believe that their faith was to be practiced in private. It was precisely because they took their common life to bear on the whole pattern of human existence that they were noticed.

The theological language in Acts for the fact that being Christian is not a private matter is “witness.” “Witness” and its cognates occur about three dozen times in Acts. “You will be my witnesses,” says Jesus to the disciples in Acts’ most programmatic statement, “in Jerusalem, and in all Samaria, and even to the end of the earth” (1:8). Paul’s calling is consistently described as the making of a “witness” (for example, 22:15; 26:16). And the unity of the church is characterized by giving “witness” to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus (4:33) -- to give only a hint of the importance the word plays in the story. As Acts unfolds, it is easy to see that to be a witness is to forgo the attempt to live privately as a Christian. Christians are those whose common life positions them for visibility in the world as a witness to Jesus Christ.

The language of witness points ultimately to the fact that thriving Christian communities in Acts are not self-existent or self-sustaining. Their visibility, that is, has a goal and purpose beyond their own mission and success. Indeed, even though they consistently found new communities in new locations, the Christians do not exist to replicate themselves. Their growth, rather, is for the sake of a public witness to Jesus Christ. In this way, Acts’ story of the emergence of Christian communities in the ancient Mediterranean world argues against the modern dichotomy between public and private life and challenges Christian leaders to guide their people toward a life of visible witness as a condition of a thriving community.

This is part of a series. Learn more about the concept of Thriving Communities »