As he walks the paths on which he played as a child, the Rev. Dr. Bungishabaku Katho can hear the early morning call of the birds. This land serves as both a reminder of ethnic division in the Democratic Republic of Congo and a place of hope for its future.

Here, at the edge of a small village in the far eastern reaches of the country, Katho -- an Old Testament scholar from a minority ethnic group -- is attempting to redeem and rewrite the unfolding story of his troubled homeland. In a region where ethnic strife has resulted in horrific massacres and revenge, he is working toward reconciliation and restoration.

Here, at the edge of a small village in the far eastern reaches of the country, Katho -- an Old Testament scholar from a minority ethnic group -- is attempting to redeem and rewrite the unfolding story of his troubled homeland. In a region where ethnic strife has resulted in horrific massacres and revenge, he is working toward reconciliation and restoration.

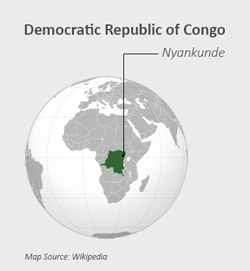

The Jeremiah Center for Faith and Society has taken root on the lush and rolling site of a former school whose damaged campus was abandoned in the wake of ethnic violence that in 2002 devastated his childhood village of Nyankunde. An estimated 1,200 people were slaughtered; the entire village of 15,000 was displaced. The local hospital was destroyed, and the town became uninhabitable for years.

Since 2017, Katho has hosted gatherings at the Jeremiah Center, which is envisioned as an ecumenical and hospitable place to stage retreats, symposia and strategic research conferences of Christian scholars and leaders throughout the country and the region.

It is a capstone of Katho’s career as a theologian, pastor and Christian leader in the Great Lakes region of Africa. Much of the region, which also includes Burundi, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, has been wracked by conflict over the past 20 years.

“What is very urgent now is to help Christian leaders arrive at a common vision, a common plan, and then listen to one another,” Katho said. “It is a gift to gather together at the same place, spending three or four days reflecting on what is going on in the region and then asking, ‘What can we do as the body of Christ under the same Lord?’”

Caring for Christian leaders

Katho’s organizing vision for the Jeremiah Center is to cultivate and care for Christian leaders, bringing them together in a place of rest and reflection while providing a backdrop for sharing ideas and strategies that can build up Christian communities.

Leaders in the region’s churches and Christian communities are too often isolated, inadequately prepared and overwhelmed by the sheer stress of doing ministry in a challenging context of poverty, disease and death, Katho said.

In addition to the continuing militia violence, for example, Congo has suffered a yearlong Ebola virus outbreak that has claimed the lives of nearly 2,000 people.

“Christian leadership calls us to understand our responsibilities during this time of many hardships in Africa,” Katho said. “We need leaders who are clear about their call. And we need leaders who are ready to sacrifice their own interests. The life of Jesus calls us to a life of sacrifice. For me, the essence of leadership is sacrificing whatever we have so that the people of God can hear again this message of hope and start making sense out of their life.”

Kurt Berends, the president of the Michigan-based Issachar Fund, which has provided financial support and counsel for the launch of the Jeremiah Center, describes Katho as “a dreamer who has credibility.”

“You can see God at work in his life and what has been done through him. He doesn’t dodge the hard questions. He doesn’t dodge the work. Here is someone who has lived on the front lines in a violent context, who hasn’t shied away from these difficulties,” Berends said. “Sometimes you could feel you’re sitting with a psalmist, a man recounting his blessings or railing at God at times.”

What are your dreams? Do you have the credibility to engage others in them?

Berends said that Katho’s ultimate aim is to “give the church a voice in civic and political life that is meaningful, charitable, not triumphalist, not about the church taking control, but bearing witness to the good news that’s a gift to all, whether people share those convictions or not.

“And if the work of the Jeremiah Center only impacts eastern Congo, if it has a transformative impact there, that’s a huge success from my perspective.”

The center, named for the Old Testament prophet whose writings and example are the focus of Katho’s scholarly work, has attracted advisers and leaders from Protestant denominations and the Catholic Church.

So far, Katho has raised $45,000 toward the estimated $350,000 cost of the center, which is expected to be completed over the next four years. Two U.S. foundations have contributed funds for programming and strategic planning.

Initial consultations have laid out an agenda and framework to guide the center’s efforts to help transform both the church and society in Africa.

The most recent gathering sought to consider three key questions: How did the Democratic Republic of Congo come to be in this place? How can genuine transformation take place? And what is the role of Christian faith communities in shaping the future?

What are your organization’s guiding questions?

Earlier consultations identified a list of research projects for the Jeremiah Center to undertake, beginning with an initiative to honor the pioneers and heroes of faith in the country, especially the first African evangelists and pastors, Katho said.

“There have been countless great men and women of God who worked for unity, lived in simplicity, encouraged love, planted and strengthened healthy churches all over the region,” he said. “Many consider this earlier time as a defining moment of spiritual formation and the development of a Christian conscience in the region.”

A modern-day Jeremiah

Katho’s own spiritual pilgrimage has had many plot twists and defining moments.

Born a member of the minority Bira ethnic group in 1963, Katho was christened with the Kibira name Bungishabaku, meaning “one who helps others.”

He was raised Catholic, but in his early 20s, while studying as an undergrad to become a French language teacher, he came to a fresh perspective on faith and belonging. Katho credits his awakening to the woman who later would become his wife.

“Both of my parents were Catholic, and we went to church when I was young,” he said. “But we didn’t really read or know the Bible.”

The Scriptures, as Katho learned from Negura Feli, his future wife, “contain God’s vision for society,” he said. “It is a vision of the flourishing of human beings. It is the biblical vision of shalom, where all things are in right and just relationship with each other, with God, with creation, with all of humanity.”

What is your vision of shalom in your context? How could you help cultivate “right and just” relationships in your community?

After completing his undergraduate training in French, Katho decided to pursue theological studies. He earned M.Div. and M.Th. degrees at the Nairobi Evangelical Graduate School of Theology (now the School of Theology of Africa International University) and later earned a Ph.D. in Old Testament from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa.

As he was finishing his studies in 2003, he was asked to step in as principal at what was then called Bunia Theological College and Seminary in Bunia, Congo, after the principal’s son was killed in house-to-house fighting.

One of the few places left untouched in Bunia was the seminary, because it had served to shelter different ethnic groups at different times and was, in Katho’s words, “the only place of peace.” In May 2003, the surrounding violence forced the school to evacuate, and 1,300 displaced persons moved in, he said.

Later, in recognition of its role in promoting peace, the school was renamed Shalom University.

“That is why we put the name ‘Shalom,’” Katho said in a recorded interview. “When the two factions -- these are ethnic militias -- when they were fighting, we made it clear that the seminary, this is a place of peace.”

The plan in 2003 was for Katho to work with the school’s president for a transitional year, but the president died just 14 days into Katho’s tenure. Suddenly, he was responsible for reopening the school, which also served as a hub of reconciliation efforts in the aftermath of the conflict, in which thousands were killed, displaced or subjected to sexual violence.

“Shalom is there for peace,” he said. “We want to stand as that sign of peace for our nation, for our province and for the entire region.”

In addition to his leadership of the university, Katho served for more than a decade as leader of his denomination, the Evangelical Brethren Church, overseeing 237 local churches.

It’s this broad life experience, combined with his vision, that has attracted attention from Christian leaders both in Africa and in North America.

“Katho is one of the most visionary people I know, and he’s made a long-term commitment to what’s needed for reconciliation in Africa,” said Paul W. Robinson, a co-founder, with David and Kaswera Kasali, of the Congo Initiative in nearby Beni. “If we in North America did a little more of the work that Katho is doing, maybe our own churches would have a better vision to make Christian faith and action relevant to people’s current needs and context.”

Do you agree that North Americans could learn from Katho? What lessons would you draw?

Robinson serves as an adviser and senior fellow at the Jeremiah Center, which he describes as “rooted in history and context, and richly consultative.”

“He’s beginning this project very thoughtfully and carefully with a time of discovery and learning,” Robinson said. “Some of his vision is intuitive, and some is deeply experiential.”

Katho’s group of advisers for the Jeremiah Center includes people he’s met during visits to the Center for Reconciliation at Duke Divinity School and to Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary in Grand Rapids.

Duke’s David Toole first encountered Katho when the Congolese leader visited the Center for Reconciliation.

“He is a modern-day Jeremiah, called back to Congo to build a new future of hope for his people,” Toole said. “Katho is unbelievably courageous. ... The courage comes from his faith, I think. It’s a courage that is tied to some deep sense of justice and a way that the world is supposed to be. Katho [demonstrates] how you live with hope and courage in the world.”

A revolution of forgiveness

This pursuit of hope amid brokenness and chaos has emerged as Katho’s organizing principle for the Jeremiah Center.

“Hope is not a naive or magical optimism,” Katho said. “It requires courage -- the courage to see a vision beyond what seems possible, to grasp that vision for something better and to live into it.”

He also said that hope animates his relational approach to leadership, which helps connect Christian leaders from different professions around a shared agenda, enabling an effective coalition for change through addressing specific issues.

Katho maintains hope in the face of almost unimaginable difficulties. Does his story give you hope?

Finally, hope is about constantly organizing and educating citizens toward the cultivation and practice of a better future, he said.

“David Kasali once told me, ‘Katho, how do you do a thing like that? You are forgiving people who wanted you to die.’ The solution is to continue loving them every day, and finally, they will say that you are sincere, not just in theory, but in daily practice.”

In his quiet but persistent manner, Katho maintains a focus on building and cultivating shalom.

He speaks about the need for a revolution in his country and elsewhere: “A revolution of love. But maybe beyond love, we need a revolution of forgiveness. … Today is the time for a revolution of forgiveness, of reconciliation, of rebuilding again.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- Bungishabaku Katho is described as “a dreamer who has credibility.” What are your dreams? Do you have the credibility to engage others in them?

- A gathering at the center considered three key questions for the work going forward. What are your organization’s guiding questions?

- Katho’s future wife shared with him a “biblical vision of shalom, where all things are in right and just relationship with each other.” What is your vision of shalom in your context? How could you help cultivate “right and just” relationships in your community?

- Jeremiah Center adviser Paul Robinson says that North American Christian leaders could learn from Katho how to make Christian faith and action relevant. Do you agree? What lessons would you draw from Katho’s work?

- Katho maintains hope in the face of almost unimaginable difficulties. Does his story give you hope?