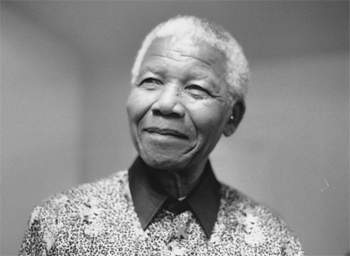

Peter Storey’s ministry has been dedicated to dismantling the South African apartheid regime and rebuilding the country after liberation.

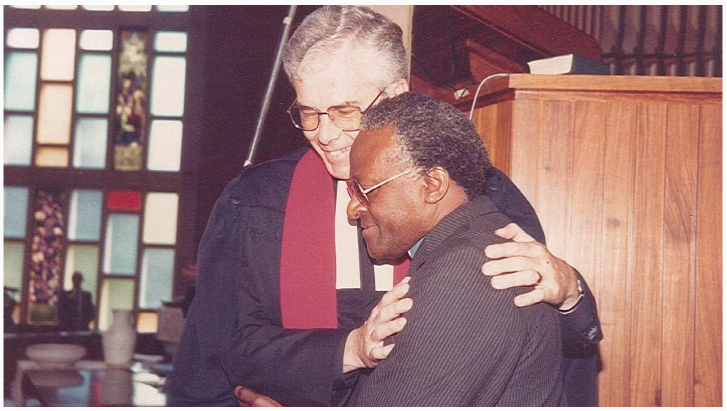

He served as chaplain to Nelson Mandela and others on Robben Island and spent decades working with Desmond Tutu to build a just society. He helped select members of the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission and has worked to stem violence in his home country, among many other efforts.

Storey is the former president of the South African Council of Churches and served as bishop of the Johannesburg/Soweto area. After retiring as bishop, he taught at Duke Divinity School, where he was named a distinguished professor.

Drawing on those experiences, he has a warning for American Christian leaders: Take your prophetic role seriously.

“I love America. I really do. I love this place. I’ve traveled here 56 times since 1966. And I’ve preached in about 130 of your cities. I’ve got a feel for the country, I think. I would hate ever to come across as a kind of distant moralizer,” he said.

“I come as somebody who has a country which has been this way and has suffered deeply for it, and is still suffering for it. I wouldn’t like it if this country has to go through that kind of horror in the days that lie ahead.”

Storey, who lives near Cape Town, spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks on a recent visit to the U.S. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: What is the work of the church in times of division?

Peter Storey: Well, I think those are the times when the church is called to be the church. And very often, it’s only such times that begin to stir the church into reexamining what it means to be the body of Christ in the world.

In our experience in South Africa, I think the church was just about as sleepy as the American church is now, the mainline churches. Quite happy to go along in its little religious bubble, doing its little religious things and rituals, until it became evident that something was happening in the society that was more than the ordinary issues that you face in every society.

Something much more sinister, something that involved a determined attempt to take over, to capture, if you like, a new and different ideology from the one that you have gotten used to and were told was the way life was in your country.

You need to ask yourself what it means to be the church before that happens. And that’s what I see in the situation in the United States at the moment. There’s a determined attempt to take the country “back” for a small minority that has been outraged ever since a lovely Black family moved into the White House. It’s been hard for many white Americans, many more than I expected.

And my shock, frankly, goes back to 2003 or so. I was teaching here for seven years, and it was the time of the Bush-Cheney invasion of Iraq. And I was asking Methodist clergy, “What have you been saying about this?”

And they said, “Nothing. We can’t say anything.” Why not? Some of them said, “Well, it’s because it doesn’t matter what we say. We’re irrelevant these days. People don’t listen to the church.” And I said, “Well, there may be a reason for that.”

And then the other [response] was, “If I do speak out, my congregation will move up and out.” And my question was, “Since when did the prophets of God keep silent just because they felt they would be irrelevant?”

So don’t use that as an excuse. The reason why you don’t have influence is because of your silence, your continued silence, and the emptying of the church of any prophetic content.

You know, it happens to be Election Day today [Nov. 8, 2022]. And I went to church last Sunday and there was not one single mention of the election in that church, not even in the prayers. There wasn’t even a tiny little prayer of, “Lord, please help people to vote according to their conscience.”

What kind of terrified church is going to have any impact on what is happening in this country if it’s silent two days before the election, any election? Ask yourself who is going to come with you into that voting booth when you go. Are you going to carry with you the pain and the suffering of any people here, or are you going to think only of yourself?

So it’s whether the church is here for the world or for itself. That, to me, is the fundamental question.

And I think long ago the mainline churches, so called, have decided that survival is really our priority. And what in fact is happening is that while buildings and structures and bureaucracies survive, the actual heart of the church is gone. It’s gone.

And so we have to come back to a church that realizes that God is much more in love with the world than with the church, and that God cares more for the world than the church.

F&L: What’s your advice about sustaining justice movements when oppression feels overwhelming and insurmountable?

PS: Part of it is knowing the end, knowing how the book ends. Desmond Tutu, when things looked totally hopeless, would say to the regime, “Why don’t you join the winning side before it’s too late?”

And he wasn’t being funny, because he knew, ultimately, the arc of the universe, as King would say, bends toward justice.

But you have to have a framework to hold you. And the framework that I found very meaningful was something that came to me as I was in Australia doing some study and the question of returning to South Africa, just at the time when it was sliding into the abyss, arose.

If I was going to return, it seemed to me, I needed to know: What does it mean to obey Jesus in apartheid South Africa?

These are the four principles that came to me, and I’ve found they’ve sort of stuck with me through thick and thin.

Be a truth teller without fear. If I’m afraid to tell the truth, I must back out of it now. You’ve got to be a truth teller. You’ve got to be willing to lose members. You’ve got to be willing to incur the wrath of the authorities. If you waver from being a determined truth teller who exposes what is happening in the light of the gospel, then you will fail, and you will buckle under it.

Bind up the broken. If you happen to be somebody my color in a country where white people are oppressing Black people, then you’ve got to make every effort you can to somehow enter into the lives of those who are suffering most.

Not that the white person can ever enter into the soul of Black suffering. But you can touch the edge of it. I don’t believe that any preaching that engages the really hurtful issues in the world has credibility unless it is preached from a platform of involvement with those who are suffering.

I would go further: Churches that are in relatively well-off situations and comfortable situations — and that often means white situations — if they want to save their soul, it’s for their sake that they need to do the journey into the places of pain.

It’s for the sake of our own souls, because that’s where we find Jesus. He identifies there far more than he would in any comfortable suburban church.

Live the alternative. If the issue is race, then we’ve got to make sure that our churches begin to reflect God’s dream for America rather than our fears of other people who are different.

In Johannesburg, I lost 200 white members when I integrated the Central Methodist Church, which was the cathedral in South Africa of Methodism. It was scary, because it looked like at one point I might be the guy who closed it all down.

But it didn’t happen. Instead, we got a beautiful community of people of all colors. We could say to the whole of South Africa, “You think it can’t be done? Of course we can live together like this. This is the kind of South Africa that God dreams of, and that’s what the church should be representing.”

I’ve got a photograph of my old congregation in Johannesburg. That photograph is a witness. It’s a prophetic statement. No one has to say a word. They just have to look at that and say, “Wow, did that happen in South Africa?” And it did. So that’s better than all the preaching in the world.

Join Jesus in the energy for change in your country. And I think that comes to your question, finally, about sustaining movements, prophetic movements. The church must get rid of its triumphalism and its arrogance. The suggestion that we are the only people that God is using to change the world is nonsense. In fact, half the time God has to abandon us because we are so useless and use other methods.

We should very humbly seek a place among other people of faith, of other faiths, of no faith, of different approaches, if you like, who seek justice.

My experience in South Africa was that if the churches had not gotten together in the South African Council of Churches, which was the spearhead of church resistance to apartheid, led by Desmond Tutu, and then broadened to include other faiths and then broadened further to include people of no faith but who were passionately committed to justice — if we hadn’t done that, we would not have been able to play the role we did.

When nonprofits and churches and religious movers and nonreligious justice movers got together and became the United Democratic Front in South Africa, it suddenly had the kind of heft and weight for the regime to really get anxious about.

And I think the lack of ecumenical engagement — serious ecumenical action — in America is troubling. The denomination still very much overpowers any kind of ecumenical thinking and action.

And that troubles me, because you [need to] take on the powers that are beginning to coagulate in this country and are beginning to think they can actually do it, which is to take over this country for the right wing and for so-called Christian nationalism. Which, incidentally, is exactly what the South African regime called themselves — a Christian nationalist regime.

I think if we think we can take them on piecemeal, we mustn’t bluff ourselves. They play very hardball, and power is a very important thing to defend in their case. And so we used to say back home, “When the church speaks out, their knees don’t knock.”

They get together to decide how they can chop our knees off. That’s what they do. And so we’ve got to be very wise about how we go about this. But we have to go about it.

It’s the absence of that going about it that troubles me when I look around here.

F&L: Do you think that something like a truth and reconciliation commission, as you had, would be helpful in our context?

PS: Oh, I do think it could. It would be very different. I’m working at the moment with a group of people in North Carolina. The center of it is the Beloved Community Center in Greensboro, who, of course, you might know, were responsible for the first truth and reconciliation [project] in America.

Now, our commission in South Africa was post-conflict, and I think this movement hopes to preempt conflict by getting conversations going. One of the things we struggled with in South Africa was how do you oppose something passionately and in principle without compromise and at the same time hold a hand out toward the people who represent that idea. We’ve got to get beyond the kind of hatred that is being generated between people.

If I claim to serve the Prince of Peace, and if that is what motivates me, then I’ve got to find a way to use the lovely phrase of Pastor Nelson Johnson of this truth commission movement: “I’m moving toward the other rather than walking away.”

I’ve moved around a lot in the last few weeks in the South, and people have asked me time and again, “Where can we start? What can we do?” And I would say, “Break the silence between you and those people who are on the other side of this chasm. Break the silence.”

Find a way of doing so, even if it’s having a coffee with somebody and asking, “I really need to know why you feel so angry.” Now that’s not easy.

I think it’s perilous times that this country is in. And I don’t believe the church has begun to think really deeply about what are we called to be in these times. I think they’re just hoping it will all blow away. And it won’t.