Education is inherently political and pastoral. I came to this belief as a K-12 public educator in the late 1990s. I returned to my childhood neighborhood, by choice, to teach a racially and ethnically diverse second grade class of African Americans, Hispanics, Latinos and Latinas, Southeast Asians, and Native Americans. I wanted to provide them with an educational experience that would inspire them to critically reflect on and transcend any social, political or economic limitations.

I wanted to build a teaching and learning community in which I would serve not only as the guide on the side but also as a student of my students’ voices, experiences and ways of knowing. These young children — our babies, as I like to refer to them — were not blank slates or mere recipients of knowledge. I presupposed that they had something to offer the world, including to me as their teacher. An integral part of my vocation was to elicit it.

To assist in this educational endeavor, I invited my pastor to pray for me and my students before the school year began. I was then and am now unapologetically Black and Christian, and a proponent of education that empowers and liberates a people and not just an individual.

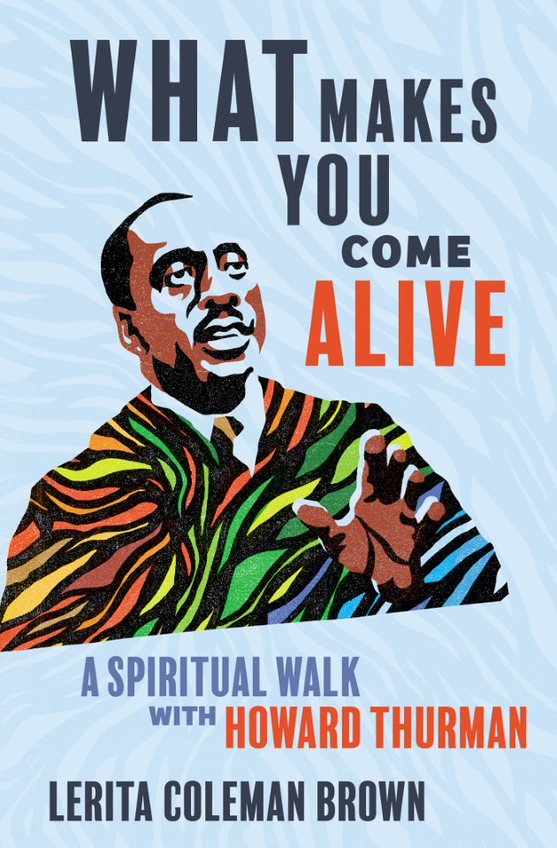

Many historically Black denominations in the U.S. have deep roots in creating and providing an education that uplifts people. Black laity and clergy such as Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, Anna J. Cooper, Nannie H. Burroughs and Howard W. Thurman founded institutes, colleges, schools and church educational ministries that humanized Black souls and transformed lives.

They provide us with models to engage the current reality of the banning of books, theoretical methods and a thorough, accurate recounting of history. They can assist us in offering a corrective, healing and redemptive approach to an education that by and large excludes or limits Black, Indigenous, feminist and womanist contributions to U.S. development.

With the contemporary onslaught of racial violence and the injustice in education, the Black church must draw from its deep roots, and the church in general must begin to develop practices of engagement.

Black congregations originated in a time when Black people could be sold, whipped or lynched for learning how to read the English language, including the text of the Bible. Today, far too many professionals at all levels of public education are being censored, penalized or fired for their efforts to provide instruction that challenges oppressive narratives and practices.

Furthermore, students, especially those in urban districts and schools, are not being allowed access to literature, curricula and instruction that can inspire and help them interrogate a world that can seem meaningless and impenetrable.

These educators and students must not stand alone. The church in all our varieties must not be silent. We must move into action as practitioners of education that is politically conscious, pastoral and transformative.

Freedom Schools are one example. For almost 30 years, the Children’s Defense Fund has provided educational programming for children in collaboration with organizations like the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Institute for Child Advocacy Ministry, a coalition of African American congregations and denominations that focuses on education, advocacy and activism.

Reading is a human right, which both groups champion for Black and low-income children and youth. By providing Black-authored materials, each agency in its own way disrupts the social, emotional and political harm too many Black students experience in school settings when they have limited or no access to books with a broader, expansive arc of U.S. history and contemporary society.

Black leaders and congregations have a rich tradition of teaching Black children and adults to read, write and access resources to become literate citizens. Both Washington and Bethune provided educational and economic models that helped Black students, families and communities do for themselves. This came at a time when the federal government refused to provide for and protect Black lives and when many local and state governments in Southern states were practicing slavery by other names, like Black codes and Jim Crow.

Today, we, as the church, can draw from this tradition to be a political, prophetic and pastoral presence in our church educational ministries. Instead of remaining silent or inactive, congregations can unleash the literature and thought of marginalized scholars through sermons, liturgies, religious education, community outreach and political action ministry.

What is happening in public education systems across the nation can ignite our respective church educational ministries if our local congregations and denominations choose to act rather than to be silent. The church should be interested in caring for beleaguered educators and miseducated students while simultaneously announcing, publicly, the value of a broader history and curriculum, especially regarding the country’s unhealed sin of racial injustice and oppression.

The Black church has gifted the broader church with resources and a history of educational political engagement. May our political, prophetic and pastoral practices, and our collective witness, become a healing epistle and illumine the way for a just education in both the church and society.

With the contemporary onslaught of racial violence and the injustice in education, the Black church must draw from its deep roots, and the church in general must begin to develop practices of engagement.