In the late 2000s, the Episcopal Church of St. James the Less had ceased to be a beacon of hope in Allegheny West, one of the poorest neighborhoods in Philadelphia. Windows were broken and boarded-up. The grass was waist-high. Mold and animal feces made spaces unusable.

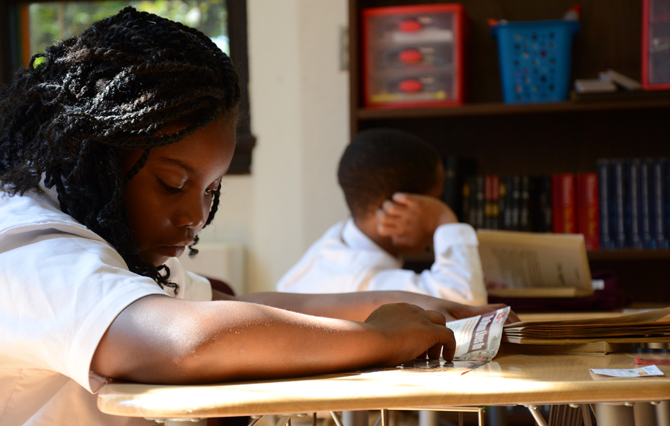

Today, the scene couldn’t be more different. St. James School, an Episcopal middle school, is completing its third year on the site. Its 46 students, all African-Americans from neighborhood families earning less than $22,000 a year, receive a tuition-free private education.

Formerly vacant spaces are now filled with sounds of children answering questions, sharing laughs and saying prayers in daily worship.

The change has been as dramatic for neighbors as it has been for the consecrated grounds. For seventh-grader Ezekiel McLeod, attending St. James means he’s not bullied anymore, as he was in public school. No longer is he shown Hollywood movies during class time in lieu of academic instruction, as he was in charter school, according to his grandmother and caregiver, Deborah McLeod.

Now he’s challenged by homework, enjoying choir, managing his anger with help from school counselors and becoming more helpful around the house, she said. That’s a recipe for staying in school, his grandmother hopes, even though he comes from a neighborhood where 48 percent of students don’t complete high school.

“There’s enough available at St. James to help him get back on track,” McLeod said. “The teachers care and love the children like we do.”

How the property was so radically transformed, in just a few years and without any change in ownership, offers a case study in how an albatross can become an asset for mission. It came to pass through a combination of resilient vision, valuable partnerships and savvy delivery of exactly what cautious stakeholders needed to feel at ease.

“We didn’t see our property as a white elephant,” said founding Head of School David Kasievich. “We saw our property as a resource for the neighborhood and for the church. We couldn’t imagine that we couldn’t come up with a way to re-purpose this property.”

An opening for a rebirth

The transformation of St. James is especially remarkable in light of its recent, painful history.

Disillusioned with what they saw as a liberal drift in the Episcopal Church, St. James parishioners tried to leave the Episcopal Church in 1999 and claim the property for the congregation. The Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania fought them all the way to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. The diocese won in a 2006 ruling that said the people might leave but the parish could not unilaterally quit the diocese. Hence, the parish would remain intact, at least as an entity on paper.

“That really left an opening for a rebirth on the property,” Kasievich said.

After that difficult episode, the diocese needed to decide what to do with the facilities. The complex straddles a busy street and includes not only a worship space but also three other buildings, a cemetery and a mausoleum. Endowment funds would cover only a portion of the upkeep costs. A diocesan standing committee, in charge during a rare three-year period with no bishop at the helm, would need to consider all its options.

Some hoped another Episcopal congregation might relocate to the site and make a fresh start there. That posed logistical challenges, and the idea didn’t take off.

“The mentality of the diocese is that our older properties and older buildings are not necessarily always well-suited for programs and for contemporary congregations,” said Andrew Kellner, the canon for family and young adult ministries of the Diocese of Pennsylvania. By and large, he said, “if we cannot find a new use for it in the short term, then buildings are put up for sale and the money is used in other ways.”

But selling wasn’t an option in this case, because of the terms of the court ruling. Stakeholders would therefore need to think creatively about what to do with this 1846 church, a National Historic Landmark in a poverty-stricken neighborhood that had seen an exodus of manufacturers over the prior 30 years.

Vision meets opportunity

Meanwhile, the Rev. Sean Mullen, the rector at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church five miles away, had a dream of opening a new Episcopal school for underserved children in this city with serious education problems.

Mullen and his flock soon learned that helping the decision-makers see new possibilities for the site would require patience and demonstration.

In 2009, St. Mark’s and the diocese partnered to host a new venture, called City Camp, at the St. James site. Day campers came from the neighborhood. Other youth, on mission trips from area churches, slept in tents. Security guards and stone walls helped ensure everyone’s safety.

The camp “enabled us to make some strong connections with the neighborhood,” Kellner said. It also built relationships with area churches, which sent youth to the camp and later became financial backers of St. James School.

Making the leap from a camp to a school on the property would involve more detailed planning -- and a lot more money. The numbers were ambitious. The school would cost around $20,000 per child to operate. Families would pay no tuition, just a $30-per-month fee.

Each year, the school would add one grade, until grades five through eight were established and as many as 68 students enrolled. For this to work, donors would need to step up and support an as-yet-unproven enterprise.

Mullen recruited one of his parishioners, a pediatric oncologist named Audrey Evans, to make a crucial gift of $50,000. Her donation would go to pay Kasievich, the professional fundraiser who would go on to become St. James’ founding head of school, but he’d need to win approval for the project first. The risk paid off. It delivered what the project needed to become reality: a plan the diocese could endorse.

Planning for success

Kasievich began his research by surveying local residents about their needs and hopes for the vacant St. James property, which revealed the need and desire for a new school.

On that front, Kasievich investigated what had worked elsewhere. He looked especially at Epiphany School, a tuition-free Episcopal school in Boston’s tough Dorchester neighborhood.

He also studied why other Episcopal schools had closed in Philadelphia. He concluded they had been too dependent on one institution, such as a single parish, for support. He therefore offered the committee a plan based on projects that had succeeded in similarly challenging environments. Among the key elements: St. James School would have a diverse support base and a team of experienced pros at the ready to offer guidance along the way.

Kasievich was convinced the project could work, but he knew he needed to be diplomatic and patient, giving others time to recognize the opportunity he saw.

“We would point to all these wonderful facts about our network of schools, how it’s helped this neighborhood and that church, just showing the results,” Kasievich said. “How could we even think of saying no to this? That’s what I was thinking always. I never said that, though.”

While diocesan staff and standing committee members were hopeful and intrigued, they needed more assurances. How could the diocese be sure St. James wouldn’t become a liability, either legally or financially?

Mullen sums up the committee’s trepidation this way: “They were very concerned to make sure they would not get stuck with the bill if things went belly up.”

To protect the diocese, St. James School was established as a private nonprofit that leases the property from the diocese for a nominal sum. Thus, the diocese isn’t responsible if the school fails or gets sued.

Meanwhile, the Church of St. James the Less continues to exist on paper, with Mullen as priest-in-charge, even as he maintains his role as rector of St. Mark’s. This structure enables St. James’ endowment to keep supporting the facilities’ maintenance costs.

By late 2010, not everyone was convinced. Some on the committee held out hope that St. James would be home to a parish, not a school or anything else.

“I responded by saying that we were opening a parish -- just not a traditional parish,” Kasievich said. “The school is a faith community. I remember saying, ‘Just be patient. The diocese will have a faith community. … It will be a community that’s worshipping, praying, having fellowship, serving others and making a difference in the neighborhood.’”

With its objections answered, the standing committee gave the project the green light in 2011. The founders were ecstatic, but the work was just beginning.

Raising money, spreading hope

St. James still needed to cultivate donors to support an annual budget, which was nearly $500,000 at the start and is now close to $1.3 million. A pivotal $125,000 gift from the Good Samaritan Foundation enabled the school to open its doors for the first year.

They look for kids who might be malnourished or in the care of a drunk parent. In such sad street scenes, where others might see hopelessness, these educators see opportunity to make a real difference in a young person’s life.

The St. James student body is truly needy; children come from families earning as little as $4,000 a year. Those with visible needs on street corners rank among the best prospects, Kasievich said, because they’re kids whom the school can help.

He also tells the rest of the St. James story: how the school provides uniforms, how teachers cultivate virtues such as kindness and courage in their students, how kids are trained in manners and cooperation as well as academic skills.

Moved by the vision, a diverse set of supporters have come through for St. James. More than 600 benefactors, including individuals, corporations, foundations and churches (Episcopal, Presbyterian and Lutheran), provide ongoing funding.

“Everybody sees education as such a hot-button issue that when they see an instance like this, where the school is trying to grapple with the problems in one of the most hard-pressed areas of the city, they jump right in” as donors, said Jim Ballengee, a member of the St. James board of directors.

The faith-based approach is especially welcome in Philadelphia these days, Ballengee added, since religious schools don’t have the profit motive that seems to drive some charter school operators.

Parents have been eager to enroll their kids in St. James, said McLeod, whose grandson attends the school, because they’re roundly unhappy with other local schools.

Other neighbors have been supportive, too. They welcome the school’s commitment to their neighborhood, according to Mark Green, a Democratic Party leader in Philadelphia’s 38th Ward, where St. James is located.

also aims to help students develop their moral,

spiritual, physical and creative gifts.

Green finds that residents appreciate the opportunity to relax on the patio furniture the school provides for them to use beside the shady cemetery. When they need space for a function, such as a funeral reception or a birthday party, they can rent a hall at St. James for a small fee.

Having St. James staff housed on-site means the educators get to visit with neighbors routinely when they’re outside gardening or walking dogs. They’re also on hand to provide students with extra help outside of normal school hours.

And when neighborhood problems arise, they get involved. When a man was trying to lure St. James girls into his home after school, for example, staffers notified police and helped keep watch on street corners in the area, McLeod said.

“Once the school was made aware of it, everybody pitched in to make sure those children were safe,” McLeod said. “If there’s anything that goes on, people at St. James make sure that they are on top of it.”

Now St. James is looking ahead to becoming sustainable in perpetuity. The school’s board of directors established an endowment in late April with $33,000. It’s a start, Kasievich said, for an institution that expects to be around for a long time.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- Are there "albatrosses" in your community you could turn into assets? Hopelessness into opportunity?

- Have you asked community members about their needs and dreams? Are you casting a vision bold enough to meet them?

- How do you build trust with people you serve?

- Before you start a new initiative, how do you learn from previous successes -- and failures?

- What kind of information is most persuasive in building support for new ventures?