When Simon Kent Fung first heard Alana Chen’s story, he was haunted. Reading the news about the 24-year-old woman’s death by suicide in December 2019, Fung was struck by parallels to his own story.

Chen was Catholic and earnestly wanted to become a nun, but after confessing to a priest as a teenager that she was attracted to women, she was encouraged to go to counseling that espoused tenets of conversion therapy. She spoke about the experience to The Denver Post in August 2019. Colorado had just passed a law barring conversion therapy for minors from licensed mental health providers but not in pastoral counseling.

Fung read Chen’s obituary and her family’s social media posts about her death and was reminded of his own experience wanting to become a priest and undergoing conversion therapy. He reached out to Chen’s family and eventually produced a podcast about Chen’s story.

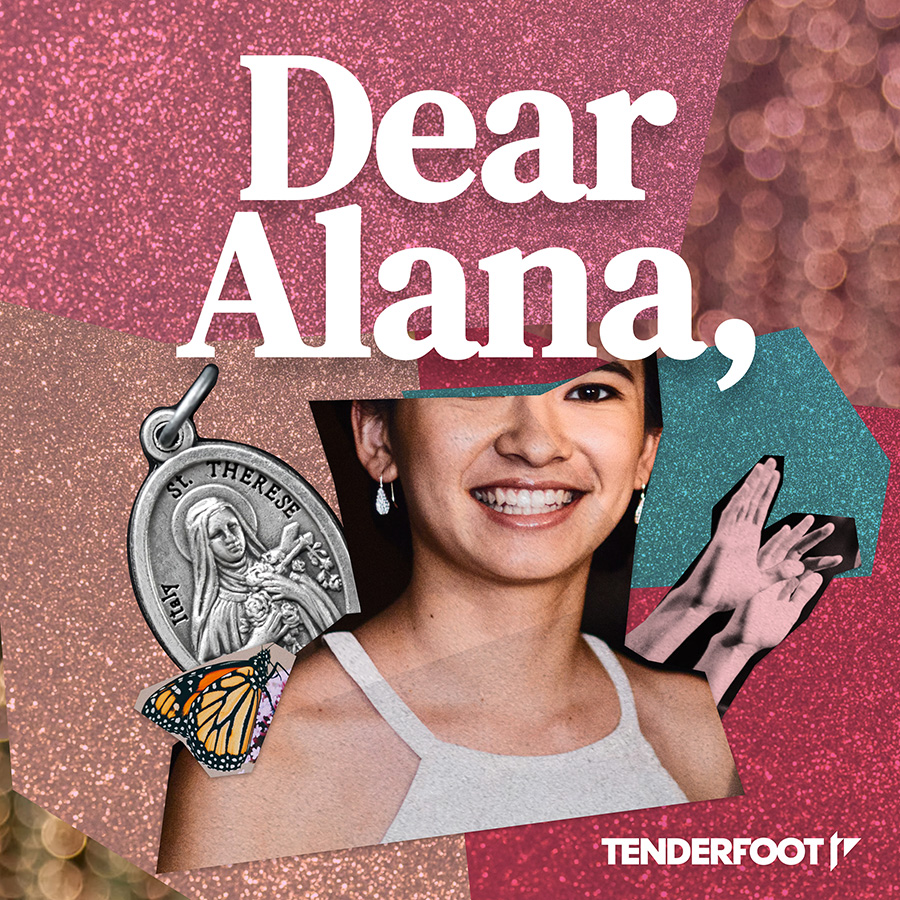

The podcast, titled “Dear Alana,” draws from Chen’s journals, interviews with her family and community, and Fung’s own journey. It recently won best personal growth/spirituality podcast at The Ambies.

Fung spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about Chen, the prevalence of conversion therapy, and the impact of producing the podcast on his own faith. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: How did you discover Alana’s story?

Simon Kent Fung: I first read about Alana’s story in the news shortly after she died. I remember being really struck by a lot of the details that the family had discovered and talked about at the time, from her devotedness to her faith, her dream of becoming a nun, all the way through to the secrets that she was asked to keep by her spiritual mentors and her alleged involvement with conversion therapy.

I remember just being really spooked by what I thought were some obvious parallels with my own story, having pursued conversion therapy in my quest to become a Catholic priest. Reading between the lines, I intuited that Alana and I were likely involved with the same part of the American Catholic Church.

I remember being in a coffee shop when I read the news and was just sobbing in the corner. I was doing as much research as I could to read about her and what had been in print at the time, which was not much more than an obituary and some public posts from her family. I ended up finding her mother on Facebook and drafting her an email.

First, I offered my condolences, but I also shared my background in some of the areas that seemed to be similar. I just said, “If you ever need to talk to anyone about any of this, please feel free to reach out.”

It was a few months later that Alana’s mother and I talked on the phone for the first time and I got to hear more from her about her daughter, about their questions and about the complete grief that they were in. That began a texting and phone friendship with her mother, and that went on for a few years until I had the idea to explore this further, in audio. But that came much later.

F&L: How did you decide to make the podcast?

SKF: About two years ago, I needed to take a break from my job in tech, and I decided to take some time off. I was just lying awake in bed at night. It was 2 a.m., and Alana’s story just kept haunting me.

It felt like there were so many unanswered questions, and also, I wanted to know to what degree her experience was like mine. The thought came to me to maybe document that journey and have that captured in some way.

The thought was to do it in audio, just because it felt like the medium that could deliver and document the nuanced and personal, vulnerable exploration that the story deserved.

I contacted her family — her mother and her sister and their attorney — and got on a Zoom with them and shared this idea, and they were immediately supportive. I ended up booking a flight out to Denver, where they live, to meet in person for the first time, and that’s all captured in the first episode.

I started making the podcast, and I thought it would take me maybe six months or so — it ended up taking me two years. The first year, it was done independently, independently financed. I just would make trips out there and gather information and research. At a certain point, it became clear that it made more sense for me to be there, to just move to Denver and be closer to Alana’s community, to the places that she would spend time in, and get a better sense of what life was like for her growing up.

I ended up moving there, and it was after that point that the family, I think, felt that the commitment to the story was there. They started to feel comfortable sharing Alana’s journals with me, to read back to back, to draw from and to learn from. They ended up opening their doors and their closets to Alana’s possessions, her journals, her electronic footprint, and that became a lot of the source material for the podcast.

F&L: What did you learn about your own faith through making the podcast?

SKF: In learning about Alana’s life, I was able to look at my own past, and my own life, with a lot more context.

In seeing Alana wrestle with a lot of these questions about her identity and how she could ultimately find belonging in her life, I was able to reflect on my own experiences of similar struggles and gain a deeper awareness of some of the dynamics that were going on.

I saw how we were both trying to earnestly follow what we were taught — but also the ways in which that earnest faith can be derailed. There can be obstacles that are given to us that are insidious, that come from a lot of the language and the historical ways in which we talk about sexuality and identity.

Seeing all this play out in the context of spiritual direction brought to light for me some of the ways in which that boundary between religious direction and mental health counseling can be blurry. And how sometimes, the most well-intentioned pastoral approach actually can be really harmful to a young person.

One of the tragic things about Alana’s story is that she placed a lot of trust in her church and in her community, and it ended up being a place that not only provided a lot of comfort for her; it also inadvertently caused harm. It’s something that she writes about and reckons with throughout the course of the podcast.

Just being able to acknowledge that the places that we’re most intimately invested in, like our families and our churches and our communities, can also be places where we acquire the most wounding is a new place for me to be with my relationship with the church.

The podcast has opened up a lot of conversations with a lot of people in my community who may not have had the same experience but have similar questions about the degree to which the certainties that they held in their adolescence and in their fervor could have been inadequate, or have been shortcuts in some way to the truth. I think that’s been an ongoing conversation.

The podcast also does highlight the ways in which the influence of conversion therapy and its underlying theories have shaped a lot of the Christian thinking and approach to working with sexual minorities and talking with them.

It has been both eye-opening for a lot of people in my community — to see that this has been happening, that I experienced this, that Alana experienced this — but also, it’s been confirmed by a lot of other people who said, “Yep, that was my experience too.”

That conversation, which the podcast covers some in the history behind some of the neo-Freudian theories and practices around sexual orientation change, is something that needs to be talked about.

The fact that both Alana and I chose to undergo these practices is something that shows that it doesn’t necessarily have to be overtly coercive. It can come from the messages we receive that make us feel like that is our only choice.

F&L: What has feedback from listeners been like since the podcast was published?

SKF: I’ve gotten personal notes from clergy and also former clergy. There’s certainly coverage in some Catholic publications.

There have been impromptu discussion groups that have started from within church spaces talking about the show. A friend of mine is a psychologist, and there’s been a discussion that’s been happening between her and other Catholic therapists.

There’s some amount of institutional engagement, but it’s primarily been lay Catholics that have been affected by it and have taken it on themselves to talk about it and organize around it.

I know that the pope has personally been made aware of Alana’s story, and officials at that level are aware of Alana’s story as well. I think that’s all positive, and we’ll see what kind of impact this has.

I’ve been most heartened by the emails and the notes that I’ve been getting from people who aren’t religious, who’ve been listening to this story and can relate to it in all sorts of ways, because the show covers a lot of themes, from belonging and belief to betrayal, and the lengths that we’ll go to to find that belonging.

People are sharing their own personal connection to these stories, even if they aren’t religious. There are also people that have written to me who, precisely because they haven’t been religious, have through the podcast been awakened to some of these religious topics that they have formerly not been exposed to. It’s been interesting to hear from them, to hear about how this has affected them at a deep, spiritual level as well.